Kate Christensen’s substantial literary reputation is based on a series of artful, wickedly comic novels centered on underdogs, losers, and malcontents. She has created a pantheon of unforgettable idiosyncratic characters. There is Hugo Whittier, the 40ish, fatally ill narrator of her third novel, The Epicure’s Lament, who is preparing one last holiday dinner on the family estate up the Hudson River before offing himself. Then there are the women behind The Great Man—the newly deceased Oscar Feldman, a philandering painter known for his nudes of women—in her satiric fourth novel, which won the 2008 PEN/Faulkner award. (One of that year’s judges described these female characters as “defiant, infuriating, and alive;” another as “vibrant, curious, eccentric, and fresh.”)

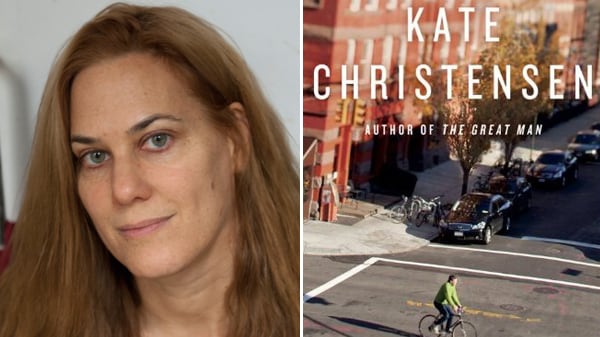

Harry Quirk, the down-on-his-luck poet who narrates Christensen’s new novel, her sixth, fits right in with these eccentrics. The Astral is set in north Brooklyn, where Christensen, 48, lived for almost 20 years (she moved to New Hampshire two years ago). She settled in Williamsburg in 1990, after a childhood in Berkeley and Arizona, an undergraduate degree at Reed and an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

Brooklyn “was very different back then,” she said, “insular, very local, and I did not belong at all. I was an outsider and a stranger; everyone else seemed to have been born there, to know one another. I would walk down the street and feel watched, studied even, an interloper.”

Christensen’s north Brooklyn is as powerful and elaborate a creation as any character in The Astral. The novel opens as Harry strolls along toxic Newtown Creek at sunset gazing at the “low mute banks” of Hunter’s Point. He passes junk shops, Mexican bodegas, opposing Arab newsstands, the old Associated Supermarket, the Smolenski Funeral Home. Later he drinks in working-class bars and works in a Hasidic-owned lumberyard. “I described the real streets and places of north Brooklyn,” Christensen said. “The lumberyard, Marlene's, the Mullet, Mazatlan, and Tom's Alehouse are all real places; I changed the names, but only in order to fictionalize them for myself. Greenpoint (and to a lesser extent Williamsburg) is a deeply affecting and powerful place, historically and socially.”

Harry’s longtime home in the novel, the Astral, is a landmark apartment building in Greenpoint built in the mid-1880s by Charles Pratt (founder of Pratt Institute) as housing for workers at his Astral Oil refinery. Christensen says she has never been inside the building, but for seven years she lived a few blocks away and frequently walked by it and wondered about it. At some point she realized she was studying it as the setting for a novel. “Harry’s voice and character emerged directly from imagining someone who has been thrown out of the Astral and wants very badly to go back—the image of that beautiful enormous red building as a lost paradise was the germ of the novel.”

Harry’s wife of 30 years, Luz, a volatile nurse, has kicked him out and destroyed his work-in-progress. She has become convinced after reading these love poems that he has been having an affair with his long-time friend Marion, a recent widow. Neither Harry nor Marion can convince Luz that she is wrong.

Based on the poetry-in-progress quoted in the novel, Harry seems at best a fair-to-middling poet. Was this Christensen’s intent? “Harry Quirk is indeed a genuinely good poet, the real thing, but he's run aground in recent years and especially since Luz threw him out,” she explained. “The poetry in the novel is meant to show him floundering in his work as he is in his life. It's meant to feel rough and off-kilter, because he's starting over, abandoning form. He says so himself, it's not going well. He tries and fails to write an epic poem about the displacement and shock he's going through.”

In one ironic scene, Harry encounters Dan, a language poet and a former rival, in the Mullet. Any echoes here of her Iowa Writers’ Workshop classmates? “Iowa was fatally competitive, scarily so,” she said. But she had no specific poets in mind. “It felt believable to me that two male poets in their late fifties, once very competitive and now both self-identified failures, would rekindle their old rivalry if they ran into each other in a bar—in the guise of joking about how washed-up they are--especially in the presence of a sexy young female bartender.”

The Astral captures the cozy pleasures and messy troubles inherent in contemporary social networks. “I have observed, through many years of living in north Brooklyn, that people, for example an ostensible group of friends, can be dangerous to one another,” Christensen said. “This loose, old social network that Harry has been part of has changed through the years—what used to be a solid group of friends has undergone fallings-out, affairs, and business deals gone awry, and is now fraught, fragmented. Walking through the streets where he's lived for 30 years, Harry encounters layers of memories. There are ghosts of past selves everywhere.”

Despite his own emotional turmoil, Harry worries about his two children, who are immersed in radical movements of their own generation. His lesbian daughter Karina, a freegan, struggles to make ends meet; his son Hector, once a Rhodes scholar, has joined an end-time cult based in Sag Harbor. “One of the major themes of this novel is an exploration of some of the ways in which people control, or try to control, one another,” Christensen said. “Cult mind control is one of the most extreme examples of this, of course. My youngest sister belonged to a group called the Twelve Tribes for many years. She recently left, with her husband and four children. Talking to her about her experiences in the group is fascinating, moving, and enlightening.”

Christensen is particularly caustic in exploring another sort of control—the power exerted over Harry, his wife, Luz, and many of their friends by Helen, a therapist whose sense of ethical boundaries is so fuzzy that she treats all three members of numerous love triangles.

Christensen acknowledges this therapist is drawn from real life. “I wanted to expose fully the extreme boundarylessness of this particular shrink,” she said. “I know of unethical, manipulative, and dangerous therapists. I based Helen on actual reports from current and past clients. Therapists have tremendous power over their vulnerable clients, and it is very easy to take advantage of this power.”

Christensen’s mother, retired now, worked as a clinical therapist for many years in private practice. “She was strongly ethical, both in terms of interpersonal boundaries and in terminating treatment when she felt her work with a particular client was finished. As a result, I have strong opinions about and reactions to therapists who cross lines and take advantage of clients, seeing groups of friends or manipulatively extending treatment beyond its completion. It gave me great pleasure to expose one of them in The Astral. Helen is not an ineffective or stupid therapist, just a rotten one.”