The newly minted Yale grad was feeling discouraged. The 24-year-old teacher had quit his day job to write a book, and only his two closest college buddies thought anything of his work. As he noted in his diary, he encountered “serious obstacles.” He couldn’t get an advance, and he “was destitute of the means of defraying the expenses of publication.”

This familiar-sounding tale of the struggling young author seems as if it could have happened last year. But the date was 1783. The man was Noah Webster, Jr. (1785-1843) and the literary offering was his legendary speller, initially entitled, A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, the first book ever published in the new United States of America.

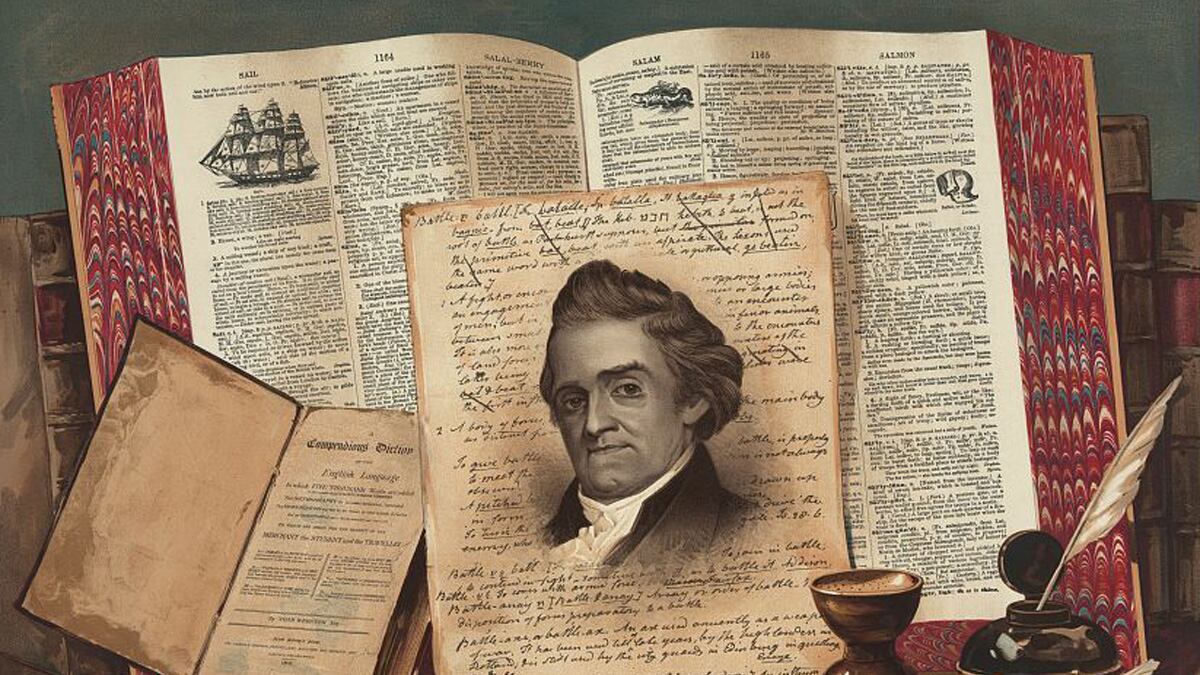

With the digital revolution now turning the book biz upside-down, we might do well to remember how Webster single-handedly put American publishing on the map. While the Hartford wordsmith is today synonymous with his American Dictionary, first published in 1828, in his lifetime, he was better known for his stupendous bestseller. The Harry Potter of its day, his text for grade-school children would sell better than any other book except the Bible for nearly a century. The final tally: a staggering 100 million copies.

In the middle of 1783, after borrowing some money from his friends, Webster cut the best deal he could get. Hartford’s Hudson and Goodwin, the publisher of The Connecticut Courant, required him to pay all the printing costs and wouldn’t spend a penny to promote the book. But fortunately for Webster, he was also a marketing genius whose “fortitude never forsook him.”

Webster soon devised an elaborate launch. He placed numerous ads in the local papers which offered bulk discounts. On October 14, 1783, a week after his pub date, Webster commandeered the front page of The Courant. Under a blurb—which he wrote himself—signed by several Connecticut luminaries including its secretary of State and the major general of its militia—Webster wrote a long essay in which he argued that his textbook was instrumental to the future success of the new nation. “Unless the Greeks and the Romans,” he insisted, “had taken more pains with their language than we do with ours, they would not have been so celebrated by modern nations.” The inveterate self-promoter readily understood that all publicity is good publicity. When an anonymous critic using a variety of pseudonyms kept vilifying him in print, Webster responded gleefully: “But under whatever shape or name my enemies are introduced to notice, they will answer all my purposes if they will rail at the Institute as much as possible.”

The media circus, just as Webster predicted, worked to his advantage. Sales succeeded beyond his wildest dreams; in a country with just three million inhabitants, the first printing of 5,000 copies sold out in a year.

The popularity of his product, in turn, created a new problem—piracy. The indomitable Webster then took it upon himself to become “the father of copyright law.” To ensure passage of the requisite legislation, Webster had to travel to all 13 state capitals because under the Articles of Confederations, the federal government had little authority. In each state, he would network with influential businessmen and publishers and personally lobby delegates to the legislature.

To fund his 13-month trip, which would lead to copyright laws across the land by the end of 1786, Webster invented the modern book tour. He became America’s first homegrown celebrity lecturer. At each stop, he would give a series of lectures on the state of the English language, for which he charged a pricey admission fee.

As the decade of the 1780s wound down, the indefatigable Webster remained astonishingly prolific. He published two other textbooks—a grammar and a reader. This fervent nationalist who was in Philadelphia during the Constitutional Convention also wrote several influential pamphlets on behalf of America’s founding document. The following year, he moved to Manhattan to edit an influential new literary magazine.

On June 25, 1788, the patriot was delighted to learn that New Hampshire had become the ninth state to ratify the Constitution, thus making it the official law of the land. But his joy wasn’t due only to the achievement of his political goals. The canny entrepreneur immediately realized that the changing political landscape might mean more money for him. “This [Constitution],” he wrote to a friend that night, “will enable me to enter into new contracts with regard to the publishing of the Institute.” And he was right. Soon after Congress passed a national copyright law in 1790, which gave authors the rights to their works for 14 years, Webster cashed in, inking a new set of deals with his publishers. All told, between 1783 and 1804, he would sell a total of a million spellers.

Webster’s hefty royalties would enable him to retire to a cushy home in New Haven—the mansion formerly owned by Benedict Arnold—in 1798. The obsessive compiler would then devote nearly three decades to his monumental American dictionary. In contrast to his predecessor, the preeminent English lexicographer Samuel Johnson, who famously opined, “No man, but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money,” Webster would compose his most enduring literary creation entirely out of love. Due to his business savvy, the Connecticut Yankee had already made a mint. To use thenautical metaphor of his granddaughter Emily Fowler, a well-known late 19th-century poet, the speller turned out to be “the little steam tug that conveyed the large East Indiaman laden with spices and silk, or the man-of-war bristling with cannon.