The phone hacking scandal certainly raises questions about the conduct of the British press and the police. But it also raises questions about the judgment of the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, and the extent to which he became so close to those at the center of the storm, including Andy Coulson and Rebekah Brooks.

Having observed one prime minister up close for many years, I’ve realized what they need almost above all else is good judgment. People can question decisions. But they like to know their leaders have sound judgment when making the many decisions they do, large and small. Personnel decisions like whom to put on your team. Policy decisions like whether News International should be allowed to control BSkyB. Personal decisions like where to spend Christmas.

For Cameron, it is not yet too late to show judgment and leadership. But as things stand, on his handling of the above, he stands exposed as having very poor grasp on either. It was only under pressure from opposition leader Ed Miliband and Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg that finally he came up today with an announcement that a judge will lead an inquiry into the scandal and broader media practices, and that the useless Press Complaints Commission will go. His opening statement was fine. But under questioning, he continued to look peevish and evasive, and in denial about the judgment problems being exposed.

Cameron got himself into a very difficult position in hiring Coulson as his communications director when the phone-hacking scandal was in its infancy, and News International and the police were still running the line that this was a tale of a rogue reporter. Lots of sensible people around him were saying, “whatever you think of Coulson, there’s this baggage. Be careful.” But the swagger and self-confidence in Cameron can sometimes become arrogance, a belief that he can do what he likes and all will be fine. It is a quality shared by a lot of senior media people.

So they willed the scandal away. So did the police. But the wrongdoing was too great and the demands for action too insistent. The relationship between police and press was so close—including via payments from journalists to police officers for information—that the police did not do their job properly.

People have said, “you and Tony Blair did the same. You got close to the press.” We certainly tried to get a better press than historically we enjoyed. But we always knew there were boundaries. If Tony Blair was beholden to Murdoch in the way people suggest, we wouldn’t have pursued such a pro-European policy when his papers were so rabidly anti-European. And don’t forget that when Blair made a speech about the press shortly before he left office—calling it “the feral beast”—he was widely vilified and the sensible proposals he made for change ignored.

I was certainly friendly with Rebekah Brooks. We spoke often when she was an editor. She was broadly supportive. But I have been speaking out about the phone-hacking scandal for some time—since before I was shown papers by the police suggesting I had been a target—and have been left in little doubt that bridges have been burned.

I fail to see how anyone can not speak out when there is so much evidence of serious wrongdoing. Yet Cameron was too slow to see the damage being done by his support for Coulson, his friendship with Brooks, and the growing sense that important decisions were not being made without fear or favor.

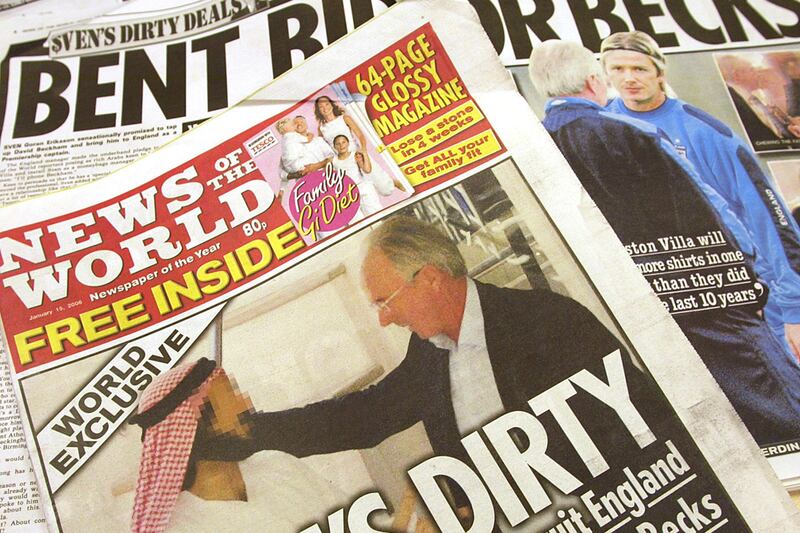

A tipping point was always likely in this saga and it came on Monday. When the phone-hacking scandal concerned only politicians and footballers and celebrities the public wasn’t going to lose much sleep over it. Now, it has risen to a different level. It turns out they were doing this to anybody—and doing it to people when they were at their most vulnerable. With people at News International still seemingly in denial about the impact of it all, out poured revelations that the families of murder victims, and the families of dead soldiers, had been hacked. It’s just beyond belief for most people, including for most journalists, and it is public revulsion that has forced the Prime Minister finally to set up an inquiry, the police to show how seriously they now take it, and News International to shut down the News of the World.

Journalism in the U.K. has been robust for many years. As one of Murdoch’s Australian editors once said to me, it was often the best and the worst in the same issue. But amid the pressures of the internet, many of our papers have become increasingly negative, obsessed with trivia and celebrity and focused only on impact. And ultimately, the case raises fundamental questions about what sort of society and democracy we live in, in Britain.

I believe that in future years, the News International management of this crisis will be studied in business schools as an example of how not to do crisis management. At every stage, they have confused tactics with strategy. They’ve put out a succession of nonsensical and often misleading statements to get them through difficult days when their strategy should have been to get to the bottom of what happened from the word go. Time and again we heard proper investigations had been done and all was well. It wasn’t.

Amid the genuine public anger about this, the luck that normally seems to come Cameron’s way has run out when it comes to the BSkyB takeover issue. People just will not understand if his government waves this through at a time one arm of the Murdoch Empire is in such disrepute. If it goes ahead, it could become another tipping point, which sees the Prime Minister’s standing fall rapidly.

The extent to which my own phone was hacked, if the notes I saw are anything to go by, is much less than others now going through the courts. But there are also in existence hundreds of invoices paid to private detective Jonathan Rees, until recently the center of a murder trial, which include some showing he was paid by papers other than the News of the World to do things journalists can’t. Ironically, given I used to work for the Mirror, most concerning me seem to be from my old paper.

The public inquiry into the press must of course go more broadly than just the News of the World. I hope other papers like the Daily Mail are also called to account for their practices; that whoever heads the inquiry will be able not just to investigate but to make recommendations for a new system of regulation.

The problem we have in Britain is that the Press Complaints Commission is a failure, a total joke that is run for the press, by the press. The former Secretary of Culture, David Mellor, used to say that they were drinking in “the last chance saloon.” But they’ve had a lot of drinks in that saloon. And things surely now have to change. David Cameron must put his own interests aside, and lead that change with only the public interest in mind.

* * * *

A vignette from my blog today: Like David Cameron, like Gordon Brown, like many others in politics, I attended Rebekah Wade’s wedding to Charlie Brooks when Labour was still in power. At the time, my partner Fiona and I were friendly with her, a friendship that waned when we lost power, and she moved very firmly to the Tories.

At one point, at the reception, I noticed David Cameron standing on his own. I went to talk to him. I said that obviously I hoped he didn’t win the election, but if he did, and if he wanted to do something about the press, then I would be willing to lend any support I could in that. I also said that he would find himself enormously strengthened as Prime Minister if he went in there without worrying about press support. It would free him to do what he thought was right. I also said I felt the importance of the press was diminishing and it was in the interests of the politicians that it did so.

He was engaged but did not exactly look enthusiastic and as he knew by then I was helping Gordon Brown, he was probably on his guard. But we did have a short, civilized conversation, during which I recall him saying “It’s got worse, hasn’t it?”

At that point, who should move into view but Rupert Murdoch? The subject changed when perhaps we should not have allowed it to do so.

Cameron can try to lump me in with Coulson, as he sought to do at his press conference. But on the issue of press standards, the uselessness of the Press Complaints Commission, the extent of the phone-hacking scandal, and the need for politicians to be firmer and stronger in the face of the new media culture of negativity, I think Tony Blair would confirm that I have been banging on about this for some years. Tony’s chief of staff Jonathan Powell used to call it my ‘stuck record’.

But if he had thought these issues through and showed real leadership and judgment, Mr Cameron would have reached the same position a long time ago.