As Britain’s senior policeman, Sir Paul Stephenson once enjoyed a solid reputation based on a distinguished record. On his appointment as Metropolitan Police Commissioner, the 37-year police veteran was welcomed as a straight-talking, dependable figure to head the London force that had become embroiled in political controversy.

That was two years ago, before the eruption of the phone-hacking scandal in Rupert Murdoch’s media empire touched the police. On Sunday, the 57-year-old commissioner abruptly announced his resignation and became the affair’s latest high-profile victim, accused of inappropriate links with Neil Wallis, a former deputy editor of Murdoch’s News of the World.

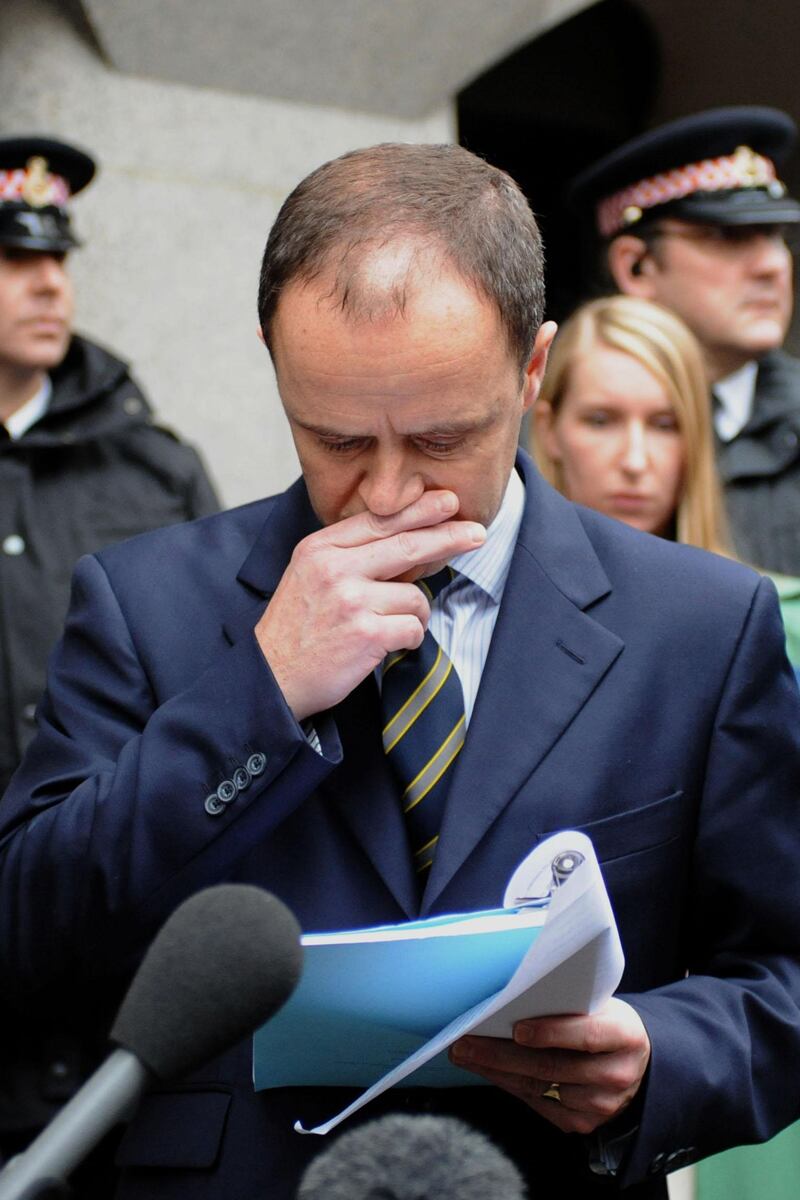

And he is not alone. Less than 24 hours after Stephenson stood down, assistant commissioner John Yates quit Monday over similar allegations. It was Yates who had checked the credentials of Wallis—arrested last week over hacking charges—when he was recruited for a valuable PR post at Scotland Yard after leaving journalism.

For the British, this is dismal news—and not only because it leaves the London police leaderless while it’s busy preparing security for next summer's Olympics. In his resignation statement, Stephenson insisted that he was leaving the job with his integrity intact. But rightly or not, the public will see his alleged failings as further evidence of wrongdoing in high places in a scandal that’s already sapped confidence across a range of national institutions.

Start with the national media. Sure, the Fleet Street press has never commanded universal respect. In surveys, tabloid reporters usually rank with real-estate agents at the bottom of the league when it comes to public trust. But the scepticism is deepening. One poll over the weekend found that 81 percent believed all Murdoch’s British titles—including the venerable Times—had been damaged.

Politicians emerge little better. It’s clear that leaders of both major parties had courted the Murdochs to an unimagined extent. According to figures released by Downing Street over the weekend, Prime Minister David Cameron has met senior officials of Murdoch’s News International group 26 times since taking office last year, a figure that doesn’t include casual social meetings with his friend Rebekah Brooks, the company’s former CEO who was arrested over the weekend.

Now it’s the turn of the police to find their reputation under critical scrutiny. One recent poll found 63 percent of the public supported the police less after the latest revelations that newspapers had paid officers for information. That’s especially harmful in a country where the police's reputation for probity has survived occasional cases of corruption. A study earlier this year found 74 percent trusted the police.

And police corruption will be of far more concern than press sleaze. As an editorial in the Times pointed out: “Unless a huge amount of what has been alleged these past two weeks is sheer fiction Britain’s police are riven with corruption on an industrial scale. Journalists who bribe policemen are indicative of a flawed industry. Policemen who can be bribed are indicative of a flawed state.”

Certainly, the facts at least raise the question of unhealthy intimacy between the police and News International. Under Stephenson’s leadership, the former News of the World editor, Wallis—now under arrest—was employed by Scotland Yard as a PR consultant. Later, while recovering from surgery, Stephenson is said to have accepted a free stay at a luxury health spa where Wallis had also handled public relations.

Or take the case of Andy Hayman, the officer in charge of the earliest hacking investigations, who dined with executives of the News of the World even while officers under his command were carrying out inquiries. Hayman went on to take a job as a columnist on the Times newspaper after his retirement in 2008. For good measure, it’s claimed that the News of the World was paying an officer of the Royal Family’s protection team for the contact details of family members.

Small wonder that critics have asked why the police skimped their initial investigations or why they chose not to reopen inquiries in 2009 when fresh evidence came to light. Small wonder too that the press, eager to see blame shifted, is pressing the issue. This is one inquiry that will last—longer than the police might wish.