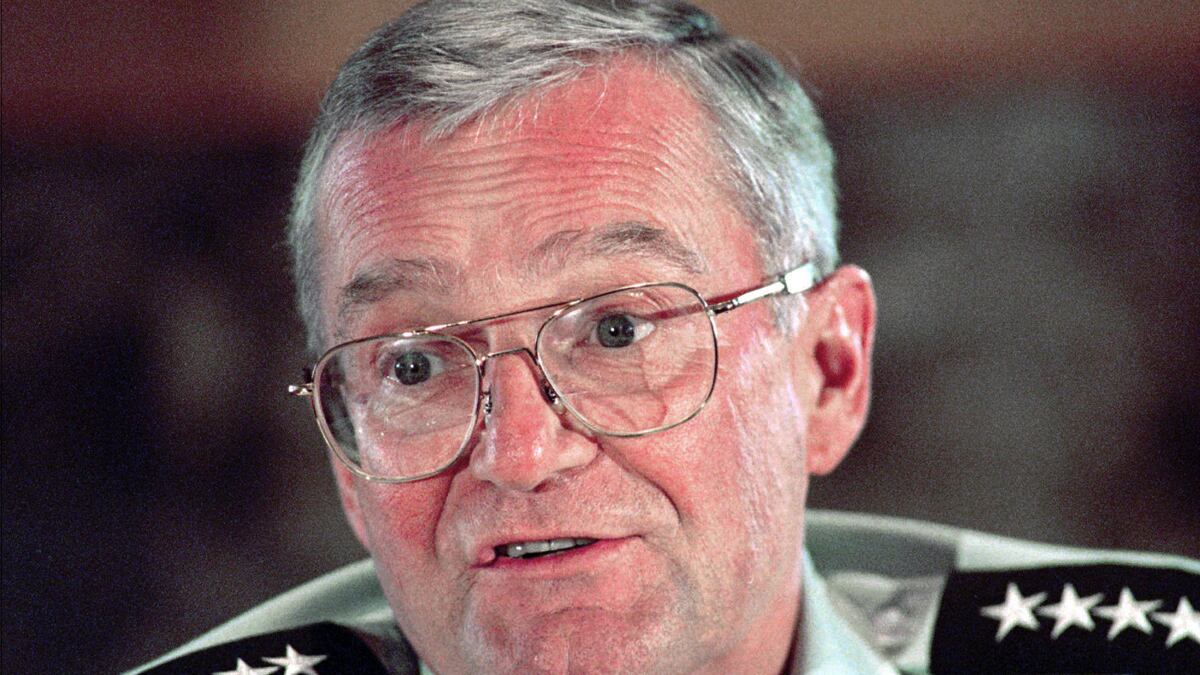

Nobody could have looked less romantic than Gen. John Shalikashvili, the former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who died on Saturday at the age of 75, after suffering a severe stroke in 2004. He was a beefy figure who never quite lost his German accent despite living all his adult life in the United States. (He joked that at least he had less of an accent than fellow immigrant Henry Kissinger.) He was the only foreign-born soldier ever to rise to the very top of the U.S. military.

“Shali” came out of the earthquakes of 20th-century Europe, and despite his appearance, his ancestry and career were the stuff of romance.

He was of German, Polish, and Georgian descent. As he told the story, his grandmother was of German-Polish nobility and a childhood friend of Princess Alix of the German state of Hesse. Alix and Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia fell in love, but parents on both sides forbade the match. When Nicholas became tsar in 1894, and thus able to ignore all objections, he married Alix. Shali’s grandmother traveled to St. Petersburg with the new tsarina.

At the court of Nicholas and Alexandra, as Alix now styled herself, the tsarina’s young companion met and married a tsarist general. Their offspring, Shali’s mother, Marie Antoinette, was born at court; but come the revolution in 1917, her family fled westward, settling in Warsaw close to the Polish branch of the family. There Marie met and married a fellow exile, a dashing Georgian cavalry officer named Prince Dimitry Shalikashvili. Shali was born in 1936.

When war came in 1939, his father joined the Polish Army to fight the Germans, then joined a “Georgian Legion” in the German Army to fight the Soviets. In 1944, as the Red Army advanced, the family once more fled west, this time in a railroad cattle car. At war’s end, they found themselves DPs—as the millions of displaced persons were called—in a small town in Germany. They lived there until 1952, when they were sponsored as immigrants to America.

The 16-year-old Shali was dropped into the alien world of high school in Peoria, Ill., unable to speak a word of English. His physique saved him from bullying—he was soon on the school wrestling team—and he taught himself English by sitting for hours after school in the local cinema, watching movies over and over. (He acquired a lifelong taste for westerns.) In 1958, with a degree in mechanical engineering from a local college under his belt, he became an American citizen—and was promptly drafted into the Army.

He loved it. Drafted as a private, he applied for officer training, and then, as an artilleryman, rapidly climbed the ranks. By 1991 he was assistant to the then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Colin Powell (himself the son of immigrants). The job invariably goes to someone likely to reach the top.

Shali’s big chance came suddenly. In the aftermath of the Gulf War, hundreds of thousands of Iraqi Kurds fleeing Saddam Hussein’s wrath gathered in the mountains of northern Iraq, along the Turkish border. Shali was given the job of getting relief to them. It was a task that spoke to his recollections of childhood, and he drove an international military coalition to herculean efforts. He brought order out of chaos; convinced a suspicious Turkish government that even the Kurds, whom the Turks despised, deserved humanitarian help; pushed Western troops deep into northern Iraq; set up tent cities on the bitter slopes; rebuilt scores of Kurdish villages destroyed by Saddam’s forces; and deterred a planned Iraqi Army advance on the camps by threatening airstrikes. The operation saved hundreds of thousands of lives—and in the process set up what amounted to a quasi-independent Kurdish statelet under Western military protection.

Impressed, President Clinton made Shali chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff upon Powell’s retirement in 1993. He retired in 1997.

Soldiering was in his genes, Shali would sometimes reflect. His lineage was not without its controversies, though—as when researchers discovered that the German “Georgian Legion” in which his father enlisted had been subsequently incorporated into the Waffen-SS. The upshot was that the most distinguished strand in his military ancestry was not one Shali often talked about publicly. By his account, the grandmother who went to St. Petersburg with the new tsarina was a von Manstein—and the von Mansteins had been generals in the Prussian Army since Frederick the Great. In World War II, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein is generally reckoned to have been one of Hitler’s abler generals. He was the primary architect of the brilliant 1940 invasion of France and the Low Countries. In the invasion of Russia, he rose to command Army Group South; some of his tactics are now case studies taught in war colleges. But von Manstein’s reputation is tarnished by his knowledge, and acceptance, of the massacres of Jews that followed his forces’ advance. He was tried for this by the British in 1949 and sentenced to 18 years in jail, later reduced to 12 years; he was actually freed in 1953.

He lived for another 20 years. Shali said he had never tried to meet the old man.