Even the most casual political observer knows how the game works: If you want to win the presidential nomination, you’ve got to go hard in Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina. You can afford to lose one of those—you can even come in fourth, just ask John McCain—but the candidate who can’t win early won’t live to fight in the other states. Everybody knows this.

Everybody except Herman Cain, that is. One look at the Tea Party favorite’s calendar shows that he’s attempting an unorthodox campaign, one that transplants the Obama campaign’s 2008 “50-state strategy” to the GOP primary. Right now, many Republican contenders are consolidating their forces in early states. Tim Pawlenty is spending so much time in Iowa he might as well live there; Rick Santorum has done him one better and actually moved his family there. Jon Huntsman has effectively opted out of the Iowa caucuses, reasoning he can’t win, but he’s flooding the Granite State with 21 staffers who are preparing for New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation primary.

Cain, though? His publicly posted schedule for July has only three days of events listed in the Hawkeye State, and another three in New Hampshire. South Carolina isn’t even on the July itinerary, although Cain was there June 29. But he has four scheduled trips to Nevada, which shares a primary date with South Carolina but lacks its influence, along with trips to a dozen other less important states, from Colorado to Tennessee and Maryland to Missouri.

“There’s a continued focus on the early primary and caucus states, but we do have a 50-state focus,” says Ellen Carmichael, Cain’s spokeswoman. “They’re not mutually exclusive—we do have a strong presence in Iowa. One doesn’t have to give to the other. That makes a tired candidate, but we’ve got a candidate who survived stage IV cancer and has more energy than all of us.”

And it’s not just the locations that are unorthodox—it’s the events. The lucky reporter who’s assigned to travel with the Cain campaign has the opportunity to visit several off-the-beaten-path events where Cain is the only presidential contender. In mid-July he hit the We Are America rally in Murfreesboro, Tenn.; FreedomFest in Las Vegas; and the Shelby County Republican Party Reagan-Lincoln Dinner in Birmingham, Ala. He was the only presidential hopeful at all three. On Aug. 2 he’ll head to the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association summer conference outside Orlando, and four days later he’ll hit the Gathering of the Eagles, an annual conservative barbecue in rural Oregon.

It’s a schedule that reinforces Cain’s image as an outsider whose ties are to the grassroots, not the party. (Cynics say that Cain, whose political experience starts and ends with a failed bid for the 2004 Republican Senate nomination in Georgia, has no choice but to run from the outside.) And wherever he goes, he seems to leave impressed fans behind.

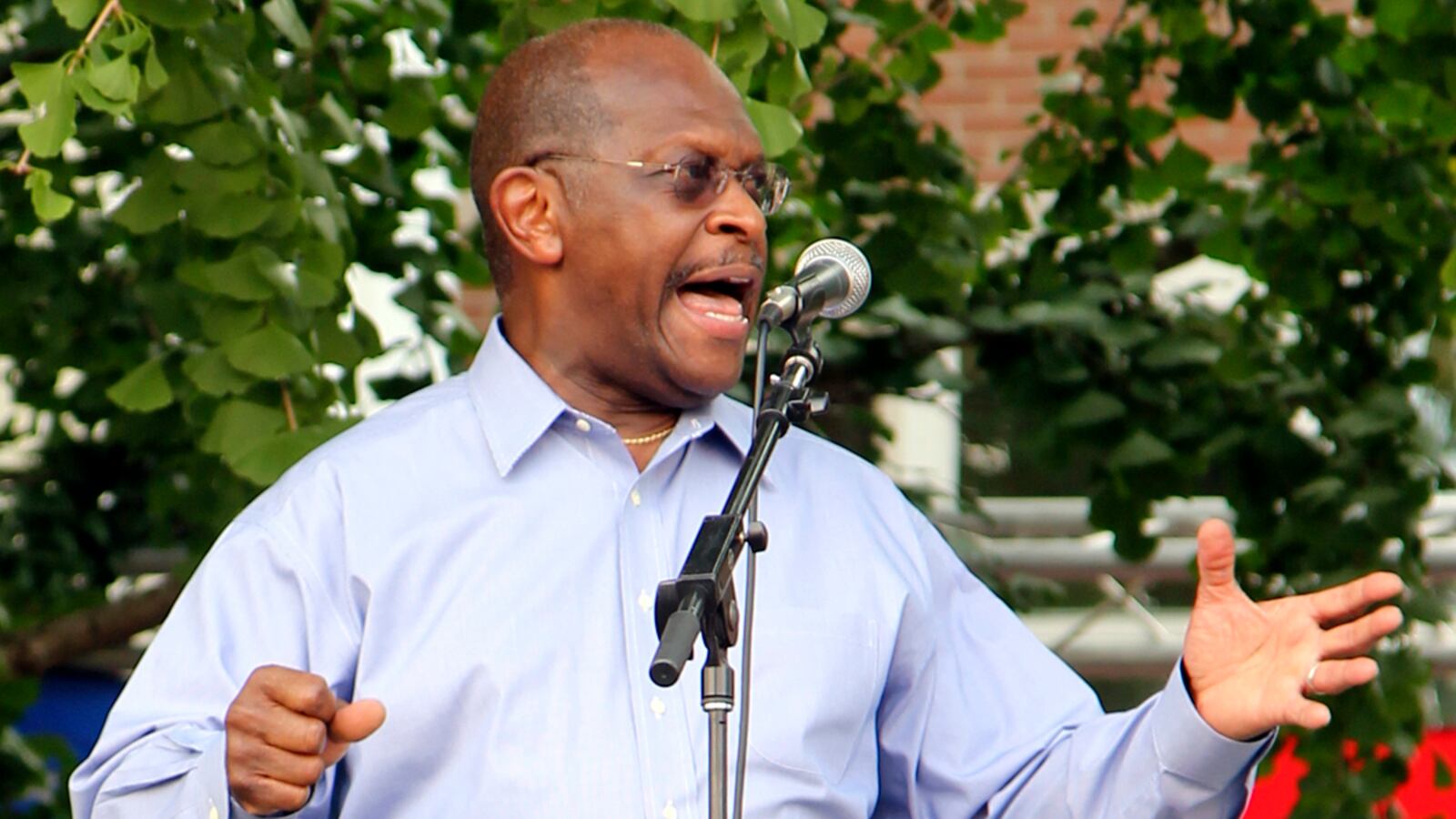

In Birmingham, for example, he spoke to a dinner of 350 people and met with three smaller groups beforehand. Although the Shelby County Republicans have gotten bigger stars in the past—John McCain spoke there during the last cycle—Cain was still a big get, and chairman Freddy Ard calls it “our best, most successful dinner ever by any measure.” Before Cain came to town, there was buzz, but he was still relatively unknown. Speaking for 45 minutes without notes, he made an impression. “The people at our event, whether they were committed to Herman Cain before or after, he made an awful compelling argument for his case,” Ard says. “He has a very unique ability to connect to people.”

Republicans in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, home to Cleveland, could be in for a similar experience at their annual picnic on Saturday. There Cain is one of two marquee names, along with nationally syndicated radio host Hugh Hewitt. Chairman Steven Backiel says the county party invited all the contenders who were in the race several months ago, but Cain was the only one who agreed to attend. “We happened to get lucky and get a presidential candidate, someone on a national stage,” says Backiel. “It’s a good get for a picnic, but it’s a big picnic,” with 700 to 800 attendees.

At the Smart Girl Politics Summit in St. Louis later that afternoon, Cain will be one of two presidential candidates to speak; the other is Thaddeus McCotter, the Michigan representative who’s the darkest of dark horses. Cain agreed to speak, but Rep. Michele Bachmann—who attended last year’s summit—declined her invite this year, opting to barnstorm Iowa instead.

And in the case of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, it was Cain—whose background in the food industry, as CEO of Godfather’s Pizza, is his calling card—who requested a slot to speak. “What happened was, he called us and wanted to speak at our meeting,” says Mike Deering, the group’s communications director. "That’s not necessarily typical. We’ve had presidents speak at our meeting before, but not candidates.”

Since the summer meeting is the smaller of the association’s two annual summits, the group told Cain to come on down and talk. His speech draft sticks to global food prices and has no mention of politics, Deering says. Cain's campaign says the event is related to his restaurant-industry interests, rather than his presidential run, although it’s listed on his campaign calendar.

Carmichael, Cain’s spokeswoman, readily admits that the calendar is more widely varied than most. “We say yes to more than anybody else,” she says. “That’s something that’s very apparent to the casual observer. We kind of determine what are high-impact events, and they don’t have to be in early-primary states.”

But what pleases groups of grassroots supporters in far-flung states—especially in small shots of a few hundred here and a few hundred there—isn’t necessarily what wins primaries. “The most important commodity for any candidate is not money—it’s time, because there’s so little of it,” says Larry Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia. “Our system may not be wise, but it is structured in such a way that all states are equal, but a few are much more equal than others, and you have to accept that.”

By ignoring that reality and spending precious time in Minnesota or Alabama, Cain is letting the remaining air out of what was already a doomed campaign, Sabato says. “There’s nobody who thinks that Herman Cain is going to be the nominee of the Republican Party except Herman Cain and his immediate family and staff. He had a bubble, as candidates often get early in the process. I wouldn’t say it’s exploded, but he’s not as hot as he was.”

Meanwhile, Bachmann has become the Tea Party candidate of the moment, stealing Cain’s thunder. Her decision to skip Smart Girl Politics and stick to Iowa shows that her campaign believes the Hawkeye State is still crucial. Indeed, concerns that the candidate wasn’t focusing enough on early states were the main cause of the Cain mutiny in early July, when some of his staffers in Iowa and New Hampshire quit the campaign. And notoriously demanding Iowa voters can be unforgiving when they feel a candidate has slighted them by spending time elsewhere.

Carmichael disputes the notion that Cain is AWOL in Iowa. Indeed, he’s spent more time there in the election cycle than any rival save Pawlenty and Santorum, both of whom he leads in most national polls—even if he hasn’t been there a lot in the last few weeks. And Carmichael says Cain already has name recognition and infrastructure in South Carolina that he developed during the 2010 midterm elections and on his Georgia-based radio show, which can be heard in parts of the state.

Moreover, she argues, the ground is too unstable to put all one’s eggs in the Iowa and New Hampshire baskets. Once again, states are jockeying to have the earliest primaries possible so as to increase their power in the process. And for the first time this cycle, delegates in early-primary states will be allotted proportionally, meaning it could pay to compete everywhere.

To most observers that’s crazy, but not the “so crazy it might work” kind. Tim Hagle, an associate professor of political science at the University of Iowa, says he was impressed with Cain when he heard him speak, but doubts that his charisma is enough to make him a winner—or even a runner-up—in Iowa. “I would still say he should focus more on the early states,” Hagle says. “It’s one of those things where I’d say, this doesn’t sound like a winning strategy, but you never know until something like this works.”