"Do you think you could write a mystery?" attorney David Renton, Alice LaPlante's partner, asked her one Friday night two years ago when they were watching Jeremy Brett as Sherlock Holmes on Masterpiece Theatre in their Palo Alto home.

LaPlante certainly had the requisite skills. She’s a short-story writer, former Stegner Fellow and Jones Teaching Fellow at Stanford and longtime creative-writing teacher (at Stanford and San Francisco State), with five nonfiction books under her belt, including Method and Madness: The Making of a Story. She had worked on a novel for years, and then abandoned it. That night she had a brainstorm. What if she were to write about a detective with Alzheimer's who couldn't remember clues? Or, what if she were to write from the point of view of a suspect with Alzheimer's, who couldn't remember whether she had committed a murder or not? Something clicked. She went to her room and wrote a paragraph: "Something has happened. You can always tell. You come to and find wreckage: a smashed lamp, a devastated human face that shivers on the verge of being recognizable. Occasionally someone in uniform: a paramedic, a nurse. A hand extended with a pill. Or poised to insert a needle."

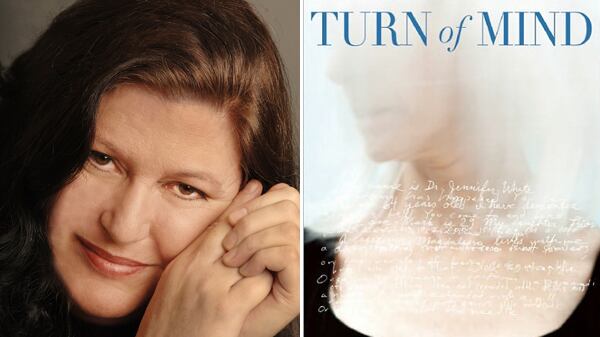

This is the opening to LaPlante's gripping and skillfully crafted first novel, Turn of Mind. It's narrated by a retired orthopedic surgeon who is accused of murdering her best friend. Turn of Mind has drawn rare prepublication attention for a first novel, beginning with starred reviews in all four prepub reviews (Booklist, Kirkus, Library Journal, and PW). It's July's No. 1 Indie Next pick, and a Barnes and Noble Discover pick.

Over lunch in an organic café in San Francisco, LaPlante told me how she wrote Turn of Mind in a creative burst. She said she promised her editor, Elisabeth Schmitz of Grove Atlantic, not to give details on how long it took her to write it, but she did divulge this much: "It was very fast. I was on a jag."

Fresh on her mind was the struggle she and her family—her 80-year-old father and seven siblings, two brothers, and five sisters who range in age from 40 to 53—have had since her mother’s Alzheimer's became evident some 10 years ago. "She has late stage Alzheimer’s," LaPlante said. "I go back to Chicago as often as I can to spend time with her every six or seven weeks. I spend a week to get as much time with her as I could while she is still there."

LaPlante has witnessed firsthand the paradox of dementia and Alzheimer's, with alternating phases of deterioration and lucidity. "One of the big problems with dementia is personality change," she said. "Many people don't realize that. My mother was a warm, kind, patient woman. When she got ill, she became aggressive. Alzheimer's patients tend to take out a lot of aggression on the primary caregiver. She's very angry at my father. She'll come back with her warm personality at times. Just less and less."

LaPlante had no need to research the novel. "I had been writing about my mother for a long time, for myself, thinking it just wasn't suitable to an outsider," she said. "It's such a downer. But this approach, with an unreliable narrator, worked."

She consulted her close-knit family. "I checked with my siblings, I checked with my dad, to make it clear that I wouldn't violate any privacy, and they were happy with that. The only autobiographical element I did put in was my Philadelphia grandparents, as a sort of homage."

Dr. Jennifer White, the narrator of State of Mind, experiences blackouts, confusion, violent outbursts, and vivid recall of events and people from her past. Amanda, the woman she is accused of murdering, was her best friend and neighbor for 30-plus years, a strong-willed and stubborn woman who, at times, engaged in vigorous conflict with Jennifer. After Amanda's body is discovered, investigators conclude that the cause of death is a blow to the head; her hand has been mutilated—four fingers removed with surgical precision.

Jennifer is an obvious suspect; her specialty is hand surgery. "I stole that part from my college boyfriend," LaPlante says. (She studied creative writing and got an M.B.A. in marketing at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.) "He's an orthopedic surgeon in St. Louis, a hand surgeon. He's a bit of a nerd. He was one of the readers to make sure I didn't make bloopers."

LaPlante also knew the tree-lined Chicago street—Sheffield Avenue—where she set the novel. "Jennifer lives around the corner from where I lived after college and before I moved out to San Francisco."

Jennifer's daughter Fiona and her son Mark try to protect her from the police investigation, but a savvy policewoman keeps finding ways to question her and build the case.

State of Mind combines family drama (sibling spats and marital breaches), the story of a long friendship (and the friendship among couples, with hidden secrets emerging with Jennifer's buried memories), Jennifer's surprising relationship with Magdalena, her caregiver, with the ongoing police investigation.

LaPlante has created an indelible character in Dr. Jennifer White, a woman who has been as passionate about her work as her late husband and her onetime lover and who struggles mightily to hold onto her life as her memory leaves her. She is coolly clinical about her own condition, cagey as she manipulates the various systems set up to restrain her, by turns charming, sardonic, and cruel to those around her as she puzzles over the fragments of her life and learns the truth about Amanda’s murder.

The ending of Turn of Mind came as a surprise to LaPlante. "I was working in the dark," she said. "The novel wasn't carefully plotted; it happened intuitively. I didn't know how the severed hand fit into the mystery. I didn't know until 50 pages from the end who had committed the crime."

Her next novel, which is almost finished, is quite different from Turn of Mind. "It's called Coming of Age at the End of Days. It's about a 17-year-old who becomes obsessed with the idea the world is coming to an end, and joins a doomsday cult and does what she can to fulfill various prophecies."