It was always going to end this way. In the hyperpartisan America where the electorate and their congressional leaders are divided like the audiences of Fox News and MSNBC, a deal on the debt ceiling was never going to be possible until the final hours.

And so for weeks, the two sides exhausted themselves with plan after partisan plan, replicating a modern-day tale of Sisyphus, the epic figure of Greek mythology sentenced to push a boulder up a hill each day only to see it roll back down.

In this case, the hill was Capitol Hill. And all the establishment leaders took turns as Sisyphus. John Boehner was pushed back down by his raucous Tea Party recalcitrants. Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid got slammed by House Republicans before his idea could even get a vote in the Senate. Reid's Republican counterpart, Mitch McConnell, tasted the same rejection from the House GOP on one of his early ideas. The bipartisan "Gang of Six" senators got stiffed on their first date with compromise, too. And President Barack Obama got alternately pushed back by Republicans and even the liberal Democrats in his own party.

All the while, Americans were aghast, wondering why Congress couldn't reach a deal and avert the Armageddon predictions being broadcast by the media in breathless fashion, complete with a doomsday countdown clock.

The good news is that pushing a boulder up the Hill can be tiresome. And after weeks of futile exercise, the exhausted troops appear to be settling on a plan that borrows from all sides, after a lengthy game of chicken with the full faith and credit of the United States.

And the final vote was likely to need some support from all the various factions in the debate to gain passage in both chambers. Leaders were hoping a combination of establishment figures in both parties, some Tea Party faithful, some fiscal hawks and some liberal Democrats would add up to reach the necessary 218 votes in the House and 60 votes in the Senate needed for passage. Three of the leaders—Boehner, Reid, and McConnell—threw their weight behind the plan to give it a sense of momentum while House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi expressed some doubt she or many in the House Democratic caucus could support it.

Obama was trying to rally those Democrats on national television, telling them he would fight for tax increases they want in the second phase of the deal where "everything will be on the table."

With Vice President Joe Biden playing the role of Monty Hall in a final episode of Let's Make a Deal, the framework that the White House and congressional leaders in both parties reached Sunday night looked like this:

- Cut the deficit in two phases by as much as $3 trillion over the next decade, a figure close to what Obama and his new golfing buddy, Boehner, originally wanted in a "grand bargain" that got shot down a few weeks ago.

- Require both chambers of Congress to vote on—though not necessarily pass—a balanced-budget amendment. That would be a victory for the Tea Party crowd, though it remains to be seen how many Tea Partiers will demand a balanced budget be enacted, not just passed, to get their support.

- Initially require no new tax or revenue increases. That would be a win in the column of Republicans who signed a no-new-taxes pledge, and the Tea Party too.

- Enact the cuts in two phases, $1 trillion enacted immediately and up to $2 trillion more identified by a first-ever bipartisan committee of Congress with equal representation of both Republicans and Democrats. Congress would enact a round of easier discretionary cuts now, and the commission would have until Thanksgiving to find the harder ones, including those involving entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security. This idea mirrors a key provision in the Gang of Six plan.

- Delay the next congressional vote on raising the debt limit until after the 2012 election. This would constitute a victory for Obama and the Democrats, who don't want to reopen this can of worms while running for reelection. This requirement, though, would be couched with a so-called trigger mechanism that would automatically impose spending cuts if the joint congressional committee fails to reach agreement or Congress rejects its ideas.

No matter the final outcome, there's little doubt the Tea Party combatants changed the entire debate in Washington. Debt limits were routinely raised by Congress until they arrived. This time it appears a debt increase will be accompanied for the first time by massive spending cuts that exceed the size of the deficit increase and without raising taxes in the short termr—something Boehner crowed about in his talk with Republicans Sunday night.

“Now listen, this isn’t the greatest deal in the world. But it shows how much we’ve changed the terms of the debate in this town,” Boehner told his Republican troops in a private briefing Sunday night.“There is nothing in this framework that violates our principles. It’s all spending cuts. The White House bid to raise taxes has been shut down."

The automatic-trigger cuts—the last major sticking point on Sunday—would be designed to be distasteful to both parties. For Democrats, that would mean across-the-board cuts to every agency—evenly divided between the military and discretionary federal spending programs.

The idea is to give both parties an incentive to return to the table to negotiate later this year, motivated to keep their sacred cows from slaughter.

"There will be a very tough degree of pain," White House economic adviser Gene Sperling told CNN's State of the Union. "That enforcement will be an incentive for both sides to compromise."

While everything was still in motion Sunday night in the tinderbox that is Congress, all sides seemed resigned to getting a deal done before Tuesday's deadline, when the United States could default on its debt for the first time in its history and see its triple-A credit rating downgraded.

If a deal is reached, Americans might wonder why it took to the very end with the stakes so high. The answer is rooted in two realities.

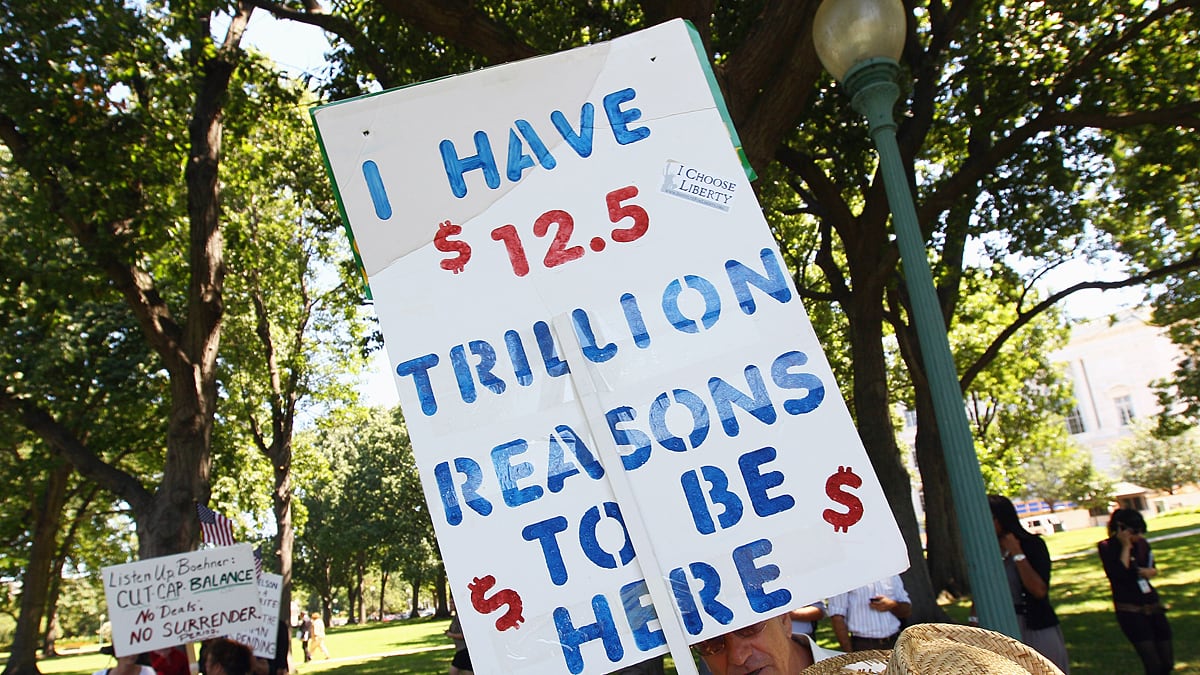

The first is the new makeup of the Tea Party wing of the GOP. It is unlike any force we've seen in Congress, and with as many as 100 sympathizers in the House and Senate, it has proved an effective, obstructive force until its demands are met.

This wing is more stubborn than the average politician, less driven by polls or doomsday deadlines, and singularly focused on the mission they believe they were sent to Congress to complete: fundamentally shrinking the size of government and enacting historic spending cuts, even to major entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security that have been off-limits to change for decades. Made up mostly of House freshmen at the bottom of the congressional pecking order, this group has exercised outsized influence.

As a result, the last-minute deal emerging on Sunday reflected more of what they wanted and far less of what Obama and the Democrats demanded at the start.

The second reality is that Congress—on tough issues—really never starts negotiating until its back is to the wall. The whole debt-ceiling drama was foreshadowed this spring, when both parties went down to the wire before reaching a budget deal. And the stakes were lower then.

But such drama isn't new to Congress, either. In President Bill Clinton's first year as president, there was a dramatic deal that passed his budget plan—by a single vote. It actually took Vice President Al Gore to leave the White House in the summer of 1993 and go to Capitol Hill to cast the deciding vote, invoking a seldom-used provision that allows a vice president to cast a vote in the Senate. The plan eked through the House by two votes.

In many ways the last few weeks have followed the pattern of tough negotiations to buy a house. Early on, the buyers often look at properties way out of their price range—or, in the case of Washington, far outside the realities of what can be accomplished. Rejection breeds a reality check, and a new target property is identified.

Then starts the long process of counteroffers—where dickering down the price and getting concessions is the goal. Walking away from the table is a time-honored tactic to identifying the real limits of both sides. Obama, Biden, Reid, McConnell, and Boehner were like the real-estate agents frantically trading counteroffers and posturing.

And a deal becomes possible only after all sides are exhausted—just like Sisyphus on the Hill. Only then can real compromise be achieved.

In the next 24 hours, we'll learn whether the Tea Partiers so essential to these negotiations toe the line and follows Congress' time-honored tradition of last-minute compromise or whether they try to play the role of the crazy uncle in the basement who tries to embarrass the whole family.

No matter the final outcome, there's little doubt the Tea Party combatants changed the entire debate in Washington. Debt limits were routinely raised by Congress until they arrived. This time it appears a debt increase, if approved, will be accompanied for the first time by massive spending cuts that exceed the size of the deficit increase.

And establishment leaders—like the president and Boehner—will have been weakened by their inability to get a deal on their terms.