At half past three on a morning this summer, four superheroes stood outside the Waverly Restaurant, an all-night eatery in Manhattan’s West Village. Despite the advanced hour, the air was still humid, and the superheroes, all members of a freelance crimefighting organization known as the New York Initiative, wore black clothing and a bricolage of metal and plastic armor, some of it homemade––titanium-knuckled gloves, elbow pads, and chain-mail breastplates.

The informal leader of the group, a tattooed former art student who calls himself Zero, stepped forward and tapped the Motorola radio strapped to his chest. “You know what we’re looking for,” he said. “You run into any trouble, and you let one of the roving guys know.”

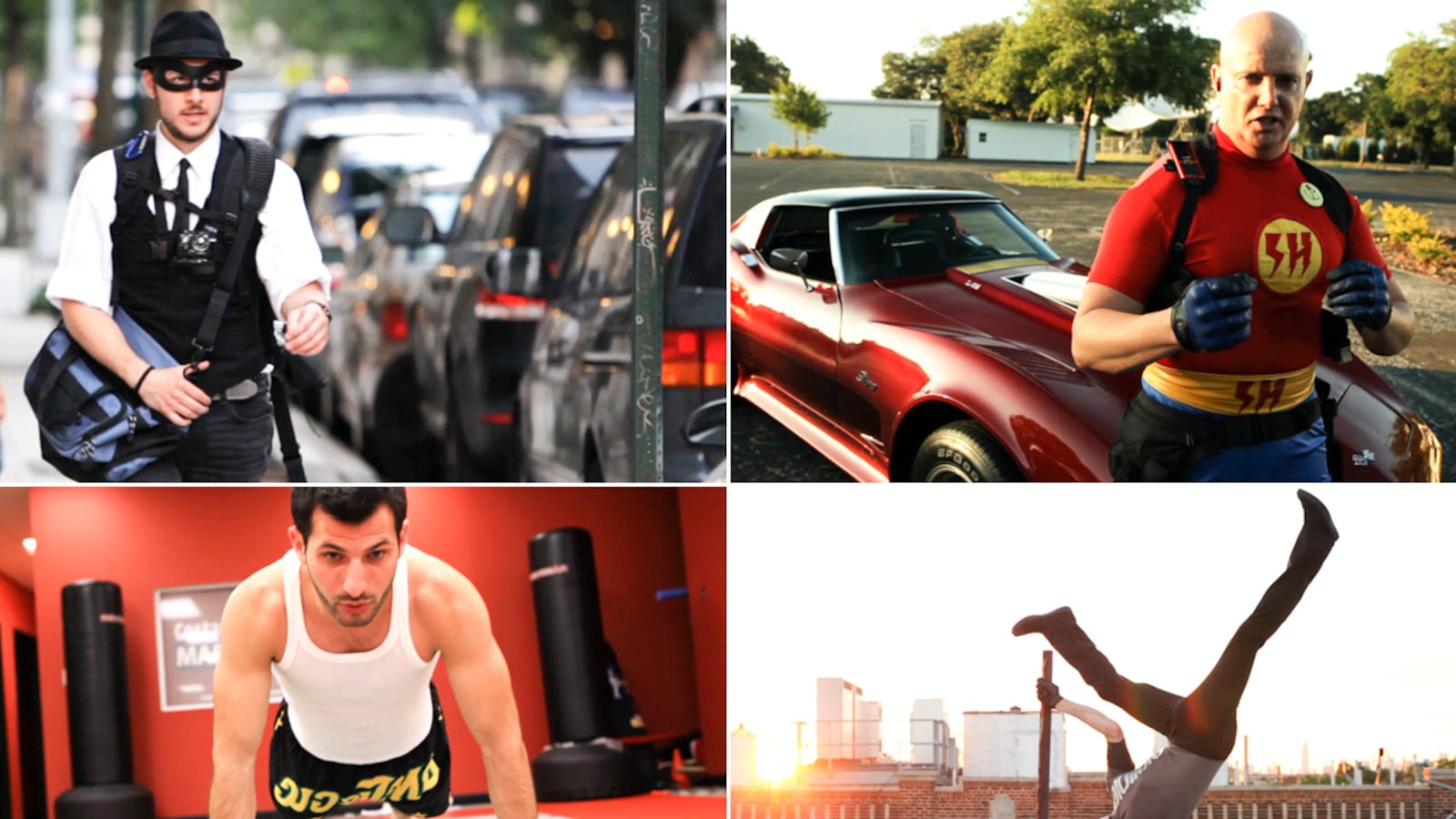

The NYI is part of a wider network of real-life superheroes––the RLSH community for short. There are RLSH chapters in most major cities in the U.S.; several groups are featured in a new documentary, Superheroes, which debuts on HBO tonight. But whereas some of these alleged heroes are no more than “cosplayers”––guys who get their jollies out of cramming themselves into plasticized codpieces, and trolling RLSH message boards––the members of the New York Initiative claim to be professionals, skilled in martial arts and self-defense. They work security or bouncer jobs during the evening, and hit the pavement until dawn, concentrating their energy on areas, like the West Village, where crime has recently spiked and the police presence is comparatively low. Most are in their teens or 20s, and all have the restless eyes and scar-flecked visages of consummate brawlers.

“You see these guys who wear spandex, and they say they go out to beat people up,” Zero said. “That’s insane. It is going to get you killed. What we do is more effective. Let me tell you something: If you’re getting in fights all the time, you’re doing it wrong.” He prefers that the NYI be known not as superheroes, but as X-Alts, short for “extreme altruism.”

(The relative toughness of the NYI did not escape the attention of the makers of the HBO documentary. “The only superheroes out of the bunch who actually look semi-intimidating are the kids from Brooklyn [naturally],” read a recent iO9 post on the movie.)

Since late April, the New York Initiative has been prowling the streetsof the West Village, usually from the hours of three to six. Their target is acrew of thugs responsible for a string of high-profile muggings, whichhave terrorized the patrons of the bars on Christopher Street. In almostevery case, the victim has been a man or woman walking from the bar to thesubway, and some bloggers have fretted that the criminals are specificallytargeting gay men. “We’ve got drug dealers, we’ve got gangs out here.We’re losing Christopher Street,” one bar owner recently complained.

I had contacted the NYI by email, and after a series of emails and text messages, Zero had agreed to let me accompany the group on a patrol of the West Village. Ground rules were laid out in advance: I would never learn the real names of the members, and at no point was I to talk “tactics,” i.e. specific martial arts skills, which Zero worries could be duly exploited by the very criminals the NYI want to deter.

At the Waverly Restaurant, I was partnered with Shade, a 23-year-old from the Bronx. “Shade will show you the ropes,” Zero assured me. “Just try to keep your head down, if possible.” A few minutes later, a black Mustang careened up to the curb, and Zero stepped down to talk to the driver, who turned out to be Three, one of the newest members of the NYI.

Three had long brown hair, and wore designer jeans, and a yellow and blue striped shirt, which concealed a bulletproof vest. He is often assigned the role of “bait”––he walks ahead of the rest of the group, clutching an iPad or a similarly conspicuous piece of hardware in his hands. This draws the bad guys out into the open, where the NYI can deal with them.

Three found a parking spot, and the six of us marched west, toward Christopher St. Zero was patrolling tonight with his best friend, the 20-something hero known as Short Cut. Short Cut, as advertised, is short. A few years ago, he fell asleep driving home from work, and crashed his vehicle, losing one arm in the process; a surgeon successfully reattached the appendage but full function has been slow to return.

“Don’t worry––I can kick just fine,” he said.

Outside the Stonewall Inn, a few patrons spilled noisily into the street, eyeing the armored X-Alts with obvious glee. “Sweet mother baby Jesus,” one guy said under his breath. “Is that a Ninja Turtle?”

______________________________________________

Zero and Short Cut live together on the second floor of a decrepit three-story walk-up in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant, not far from the border of Bushwick. The apartment once served as the official homebase for the original New York Initiative, but the founding members have since peeled off––Lucid to Alaska, to care for family, and Zimmer to Texas, where his mother is facing charges for shooting a rifle at a census worker.

I visited Zero and Short Cut here on the last day in May, not long after the West Village patrol. They showed me into the living room, which is dominated by a punching bag. As we talked, a small mouse trotted blithely out from behind the shelf. A few seconds later, a high-pitched squealing arose from the kitchen. “That’s when you know you have a mouse problem,” Zero said. “When there are so many of the things that they’re fighting for turf.”

Zero is tall and twitchy and densely built. He grew up fighting––in his first schoolyard brawl, in seventh grade, he bit through his opponent’s finger, almost all the way to the bone––and in his teens, he joined a local fight club. (The official brand of the club is still visible on his right arm.) He was kicked out of two high schools, before finally enrolling in a third, a “last-ditch” school for problem students. The program suited him, and he was accepted at art school, but after graduation, he found himself adrift again. For six months, he was homeless.

“I feel in my heart that this”––the NYI––“is the only thing I can do with my existence,” Zero said. “All that rage I used to have, it’s gone. If I had any rage, I wouldn’t continue doing this. If I had any rage now, you wouldn’t be talking to the same person.”

I asked Zero and Short Cut if they ever got lonely. “I kinda do miss coming home to a cooked dinner, and someone that cares about me,” Short Cut admitted. “Before, I was in sales. I had a good life. A girl. A good job. Right now I miss the money. I just sold some of my stuff to cover bills.” (Zero works a security gig in the city; Short Cut is currently unemployed.)

“He’s committed though,” Zero said. “Really committed.”

But certainly there will come a time when the NYI hangs up its masks, I pressed. “Picture yourself on a plain,” Zero said. “There are a lot of people, and there’s a huge flood coming. There’s a big dam, but it’s not held up by anything. All of us are up against the dam, and our muscles are popping, and some of us falling down dead. Behind us, there’s a ton of people watching, waiting, seeing if it’s safe to step in.” He rose to his feet.

“Listen,” he continued, “if every person would just stand up and put his finger in that dam, just one finger, we could all just live our lives.”

“But that’s never going to happen,” Short Cut said.

“Never,” Zero agreed. “Which is fine.”

At around midnight, we moved to Zero’s bedroom to get suited up. The room, which faces the street, doubles as an armory––the back wall is covered with bulletproof masks, all of which Zero creates himself. Zero pulled a small box off the shelf and presented it to me.

Inside, a miniature corpse lay on an operating table in a tiled room. Blood leaked out across the floor; a bucket at the foot of the table appeared to contain human organs. It was an art project from a couple years back, Zero explained––he had molded the corpse from wet clay, used dollhouse parts for the furniture, and fruit for the organs.

I asked Zero if he ever contemplated taking up art full-time again. “Whenever I try to have a normal life,” he said, frowning, “I find that I’m stopped at every turn. I try to do something with my personal life, with my career, it feels strange. It feels exterior.”

______________________________________________

In our first tour through the West Village, I had not worn any body armor, but this night we were set to patrol a rougher neighborhood, and Zero had arranged for me to borrow a Kevlar vest. The vest was surprisingly light, and rated to protect against knife attacks and 9-mm shells. (The only thing that’ll get you is one of those cop-killer bullets,” Zero said, not exactly reassuringly.)

Outside a few girls sat on an adjacent stoop, eyeing us with obvious suspicion. Part of the problem was our Motorola radios, which crackled and made us sound like cops; everywhere we went that night, heads turned. We set off down Monroe Street, me on my bike, and Zero and Short Cut on long boards. All of Bed-Stuy opened up before us––Patchen Avenue, Malcolm X Boulevard; pristine brownstones and hulking gothic schools, playgrounds and vacant lots. Further west, the street sounds melted away. Cats wandered bleary-eyed into the street. The spring foliage was dense and thick, and hung low over the street. There was something pleasantly otherworldly about the scene––something hushed and deeply weird.

At the corner of Gates and Bedford, Short Cut, who was several yards ahead of us, held up his fist. A man was leaning against a wall, watching us. He was built like the front-end of a Hummer. He nodded to us, and then gave us his back and proceeded down Bedford, lurching a little at the hips, swinging his arms as he walked.

“Let’s follow him,” Zero said into the Motorola. “Slowly.”

The guy looked over his shoulder, and Zero and Short Cut stopped. I braced myself. After a few more steps, the guy turned again, and this time ducked into a narrow stairwell. We watched him disappear into darkness.

“That guy was looking for trouble,” Zero said. “You could tell, right?”

Short Cut opened up a text message on his phone. Snipe had been kicked out of his home, in the Bronx, and needed a place to crash. Zero and Shortcut exchanged a few private words. “Let’s get you home,” Zero said.

At the stop, I stripped off the vest, and unclipped my Motorola radio. I felt a little naked. A pretty, indie-rock type walked out of the subway, clutching her bike. She was wearing black tights and a billowy white shirt, and she was very lost. “How do I get to Williamsburg?” she asked. Short Cut pointed, but the girl was already fingering the fringes of his bulletproof vest.

“You guys superheroes or something?” she smiled, and then she climbed on her bike and pedaled away.

______________________________________________

In July, I returned to the West Village with Zero, Snipe, and Short Cut. The night was quiet, boringly so, and for several hours, we walked around, waiting for something to happen. In fact, much of my time with the New York Initiative was like this––long stretches of calm, punctuated by short jolts of adrenaline. In comic books, the villains are always polite enough to wear their criminality on their sleeves. In real life, however, it isn’t always easy to distinguish the good guys from the bad, or the moderately thuggish from the totally bonkers, and Zero is fond of saying that only shit-stirrers or maniacs can ever consistently find a good fight. “Wear comfortable shoes,” he had told me, more than once.

By five in the morning, the sky was lightening, and we trudged back toward Christopher Street, where I could catch a train home. At the lip of the subway stairs stood an exceptionally drunk man, dressed in tight pink pants, and a shredded black shirt, which was cut just high enough to reveal a pale and hairless beach of stomach. I later learned his name was George.

George was being followed by a second man––larger by at least a foot, and heavier by a good hundred pounds––and as George lurched forward into the street to hail a cab, the second man grabbed the messenger bag that hung around his neck. George went limp, and for several seconds, he and his assailant did a strange little waltz on the corner of Seventh Avenue, George twisting and thrashing, his face hidden behind a veil of greasy blond hair, and the assailant patiently assuring George that he would just hold onto the bag until morning.

“No,” George said, but it was too late––in one fluid motion, the other man reached forward, lifted the bag over George’s head, and hoofed it east, striding purposefully but casually toward Sixth Avenue.

“Let’s go,” Zero said.

He and Short Cut caught up with the thief on Washington Place, just past the leafy fringe of Sheridan Square. The guy sat on a stoop not far from Sixth Avenue, flanked by an equally large friend. “Is that your bag?” Zero asked.

“It belongs to a buddy,” the man said. His friend circled behind Zero, who neatly pivoted to his right. Later, Short Cut would tell me that this was the decisive moment, when the “bad guys” were deciding whether to pounce, or to play it cool. “I was ready to kick out their fucking kneecaps,” he explained, gritting his teeth. In the event, no knee-kicking was necessary––the thief only smiled, and held forward the stolen merchandise.

“Whatever, man,” he said. “Take it.”

“You got his shit in your pockets?” Zero asked. “Stand up.”

Inexplicably––for neither Zero nor Short Cut had identified themselves as law enforcement, or anything else, for that matter––the man obeyed, and even turned his ass towards Zero and Short Cut. “See? Got nothing in my pocket. Just my wallet”––he produced it––“and some plastic bags. Some cash.”

“Whose cash?” Zero asked.

“Mine.”

A long silence passed between them.

“Get lost,” Zero said finally. Back at the corner of Seventh Avenue, he presented the bag to George, whose every joint seemed to have emulsified. He lurched hard over the curb, his hand raised toward the passing cars.

Two cabs passed. A third stopped, and Snipe trotted forward to chat to the driver. Together, he and Zero bundled George into the back seat, where he promptly plummeted facedown onto the leather.

“Port Authority please,” Snipe said. He and Zero and Shortcut gathered on the curb, a few inches apart, and Zero waved goodbye, like a proud parent seeing off a college-bound kid.

“Well, that was interesting,” Short Cut said.

“Yeah,” Zero said, “one criminal down, seven gazillion to go.”