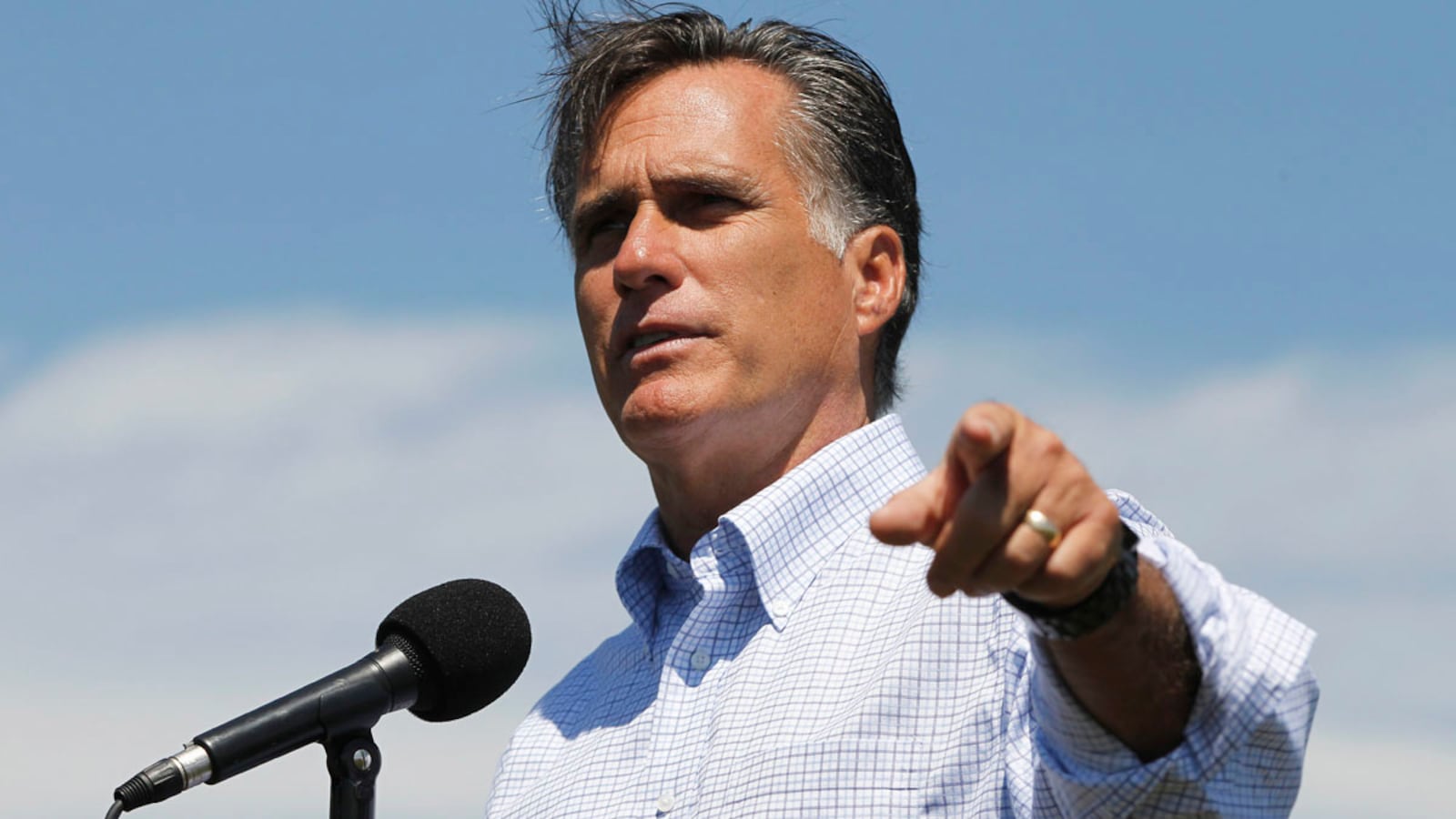

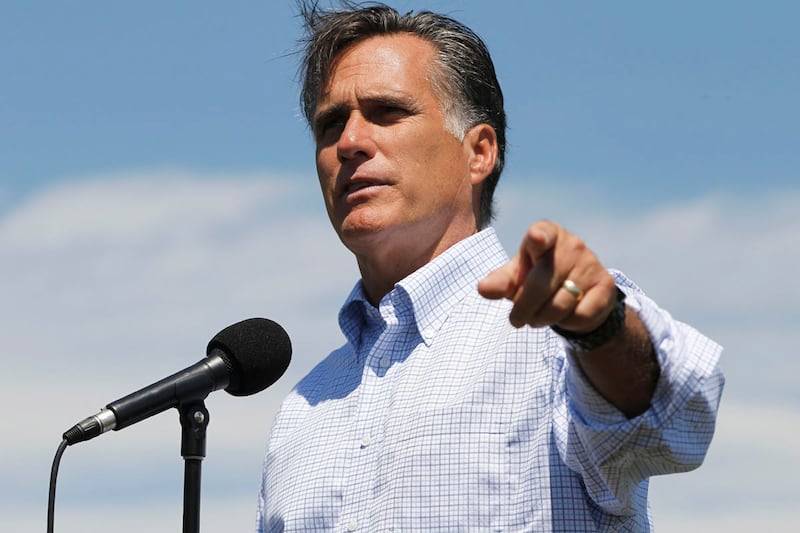

“David, how are you?” Mitt Romney says as he strides into a conference room at the local headquarters of Vermeer, a 63-year-old family-owned and -operated agricultural machinery company in Pella, Iowa, and starts reaching for hands to shake. In the time it takes a nonpolitician to blink, he glances at the next name tag—“Mike! Great to be here”—and then the next, and the next, all the way around the table. “Gary! Curtis! Dennis! Doug! Robert! Diane! Bob! Barb! Ted!” If he didn’t throw in a few “nice to meet you” lines, you’d think Romney was greeting a bunch of old friends.

And so it begins, with a tableful of besuited business leaders, signs for stump cutters, crush chippers, and trenchers on the wall, 43 journalists watching from the wings, and the friendliest tone and firmest handshake he can muster. This, finally, is Mitt’s Iowa campaign.

Or is it?

To say that Romney has mixed feelings about Iowa would be something of an understatement. Schizophrenic is more like it.

In 2008, during his first run for president, Romney invested more than $10 million in the Hawkeye State. His goal, of course, was to win the caucuses. For a while, it looked as if he might succeed: thanks to his big spending and incessant barnstorming, the former Massachusetts governor established a lead in the polls in May 2007, expanded his edge to more than 15 percent in August, and was still frontrunning at the start of December, one month before the big day. Then something named Mike Huckabee happened, and the rest is history.

This time around, Romney has been less, shall we say, enthusiastic. Before Wednesday, he visited Iowa exactly once this year, in late May. Unlike Tim Pawlenty and Michele Bachmann, he has yet to air an advertisement on local television. His paid staff—three people—is much skimpier than it was in 2008, when dozens of Romneyites flooded the state. He’s made it clear that he’s not competing in Saturday’s Ames straw poll, the early turnout test that he won in 2007—even though his name will appear on the ballot.

And yet here’s Mitt, campaigning in Iowa all of a sudden: Wednesday in Pella and a house party in Des Moines; Thursday at the State Fair and the Republican debate in Ames. He even revealed at the Vermeer event that he’d “like to do darn well in those caucuses” and promised that “you’ll see me plenty.”

What gives?

Judging by his latest visit, Romney now appears to be pursuing a Goldilocks strategy in the Hawkeye State: not too hot, not too cold. In other words, just right.

Of course, if Mitt & Co. had their druthers, they probably wouldn’t be bothering with Iowa at all. Bachmann is this year’s Huckabee: far more attractive to the state party’s heavily evangelical rank-and-file than Romney, a Mormon, will ever be, and a native daughter to boot. It would be pointless to spend the next few months duking it out with her only to lose on Caucus Day. And while it’s necessary for a first-time candidate to prove himself at the straw poll and later, in the caucuses, it’s far less imperative on run No. 2—especially when you’re ahead in the national polls. As Romney’s state co-chair Renee Schulte told MSNBC Wednesday morning, “This year, it would not make sense to use your resources on name recognition and name ID and the early television and all those things ... because his name ID is already high, and people already have respect for him."

But while Romney may have planned to skip Iowa entirely at first, he no longer has much of a choice. This weekend, Texas Gov. Rick Perry will signal his intent to vie for the Republican presidential nomination with a speech at the Red State conference in Charleston, S.C. He’ll instantly become Romney’s chief rival. It’s one thing to cede Iowa’s values voters to Bachmann; it’s another to cede the state’s fiscal conservatives to Perry, who plans to run on his record of job creation. If that happens, Perry will head into the rest of the early primary states with a dangerous burst of momentum, and Romney will be left looking like old news.

So he has to play some defense. Cultivate his 2008 supporters; make enough appearances to fortify his rep as the “economy candidate” but not enough to raise expectations; and hope that Perry and Bachmann are left battling over social conservatives come caucus time—a battle that could conceivably split the values vote and boost Romney to a better-than-expected finish. As Romney put it Wednesday, “those people who think that the economy is what really is essential in providing a brighter future for our families and preserving our values”—the economy, as opposed to, say, stopping gay marriage—“are going to look to me as someone who knows how the economy works and can get it back on track.”

That’s Mitt’s first balancing act. The other? Executing his under-the-radar strategy without alienating Iowa’s general-election voters. In 2008, Barack Obama won Iowa by 9 percentage points, but the state tends to swing. During a small press conference after the Vermeer event, Romney was asked whether he needs to “play aggressive” over the next several months in order to sway Hawkeyes. He made some awkward noises about the caucuses—“I’ll be participating in the process, hoping to win the delegates that I’d like to have to win the nomination”—before pivoting to a subject he was clearly more passionate about.

“Let me make this prediction,” Romney said, soybean plants and corn stalks swaying picturesquely behind him. “[Obama] won’t carry Iowa in November 2012. He won’t carry Iowa because Iowans recognize that his presidency has failed ... If I’m the nominee, I’ll of course be aggressively campaigning here. Iowa, of course, will be a swing state. And I think I’ll win it.”

Back when he was a businessman, Romney was famous for his strategic thinking. To pull off the Goldilocks trick in Iowa—be warm enough to protect himself from Perry and preserve his general election chances but cold enough to lower expectations for next year’s caucuses—he’ll need all the strategy he can get. And just the right number of “nice to meet you’s.”