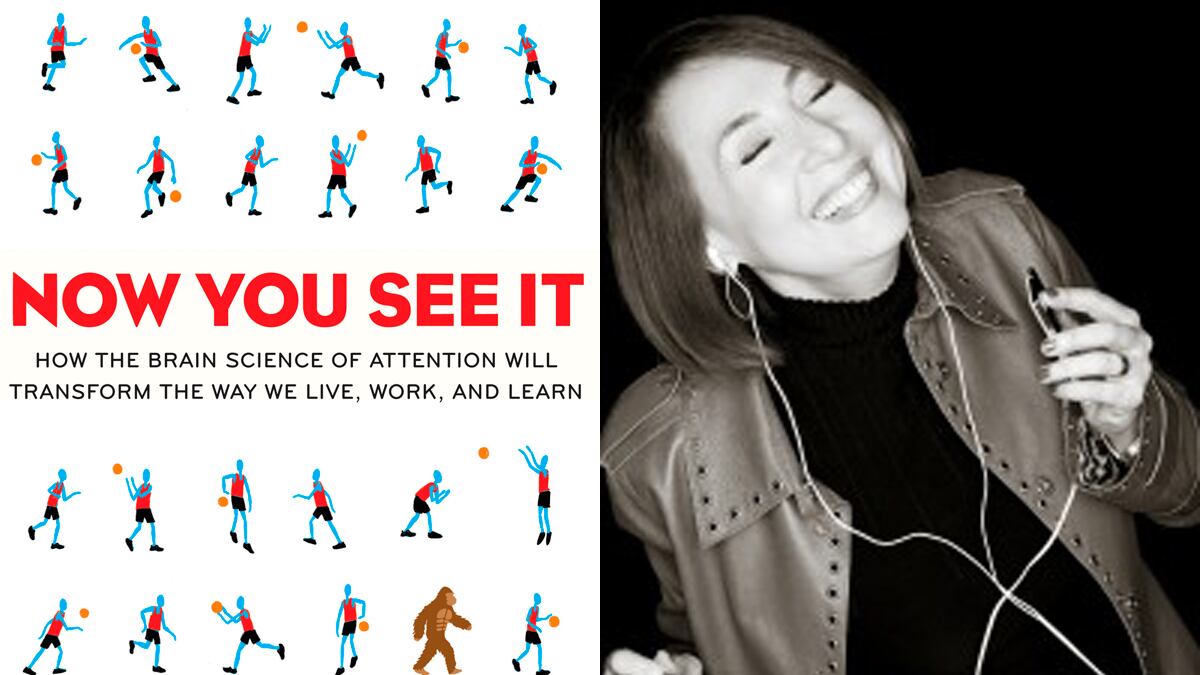

Cathy N. Davidson remembers a lunchtime lecture at Duke University a while back in which the speaker, someone from the university’s medical school, told the audience he would play a video of people tossing balls back and forth and asked everyone to keep a close count of how many throws were made. Davidson, a Duke professor—and dyslexic—didn’t even try. Instead, she leisurely watched the tape. In about 30 seconds, a figure in a gorilla suit wandered across the screen, stopped, beat its chest and wandered off. It turned out only Davidson noticed this creature—everyone else had been focused exclusively on the assigned task.

That experiment on “attention blindness” is at the heart of Davidson’s new book, Now You See It: How the Brain Science of Attention Will Transform the Way We Live, Work, and Learn. Attention blindness—the fact that we perceive only a fraction of everything going on around us—is a basic characteristic of the human brain. It’s also a saving grace, because we’d be incapacitated by the amount of information assaulting us if we noticed it all.

And yet, in her new book, Davidson argues that our attention blindness is a big problem that must be addressed—especially now that the Internet has come along and changed everything about how our lives work. The Internet, she notes, has thrust us into an interconnected, collaborative existence, marked by the total breakdown of barriers between work and leisure, public and private, home and office, domestic and foreign, and so on. She argues that although our lives have been irrevocably altered, our most important institutions are not. Those core institutions—school and work—are behaving for the most part as if nothing epochal has occurred.

“As long as we focus on the object we know, we will miss the new one we need to see,” Davidson writes. “The process of unlearning in order to relearn demands a new concept of knowledge not as thing but as a process, not as a noun but as a verb.” The challenge of meeting our radically altered circumstances is huge—a “mismatch,” Davidson repeatedly states, between our digital lives and our daily lives. And we can’t do it alone.

You may have heard of Davidson. In 2003, Duke University, where she was a provost, decided to give a free iPod to every incoming freshman that year—as well as any professors, and students in those professors’ classes, who came up with innovative ways the iPod could be used for education. It is this iPod experiment that seems to have best schooled Davidson in the lessons of our current “mismatch.”

Outside of Duke, many people greeted the experiment with ridicule, even outrage, some calling it a chance to get a free iPod. But at Duke, students were downloading audio archive materials relevant to their courses; recording lectures and listening to them outside of class. At the School of the Environment, students conducted interviews with local families and compiled them to create an audio documentary; at the Medical School, students created an easy-to-access audio library of every possible heart arrhythmia, that, in the future, any doctor with an iPod could listen to on the spot, in real time. There were hundreds of other applications.

And for Davidson, and, perhaps, for many students at Duke, the experiment was not just about developing nifty new apps. “The iPod experiment was an acknowledgment that the brain is, above all, interactive, that it selects, repeats, and mirrors, always, constantly, in complex interactions with the world,” she writes. “The experiment was also an acknowledgement that the chief mode of informal learning for a new generation of students had been changed by the World Wide Web.”

Davidson and her colleagues understood that they had on their hands a generation of kids—those born roughly after 1985—that had grown up imprinted by the World Wide Web. And yet, she says, in 2003, most “schools of education were still training teachers without regard for the opportunities and potential of a generation of kids who, from preschool on, had been transfixed by digital media.”

In what is perhaps the strongest section of this book, Davidson argues that what we’ve come to think of as being the “natural” structure for our schools— specialization in discrete subject areas, one-size-fits all standardized testing, and rigid hierarchies based on official expertise—is anything but natural. That approach was put into place to prepare students to enter the industrialized 20th century economy, where division of labor, efficiency, and clear-cut structures were most important. Now, though, many of those jobs no longer exist—or if they do, they’re in Bangalore or Beijing. Yet American schools continue to reinforce 20th-century values that prepare children for a 20th-century work force—and fail to prepare them for the one they’re actually entering.

And that’s true for the workplace as well. We’ve been trained to assume that working hard means focusing on a single task to completion, then doing it again. But, says Davidson, “the new workplace requires different forms of attention than the workplace we were trained for.”

The result is that we feel anxious and guilty, convinced we’re not getting enough done, not achieving an honest day’s work, failing to live up to the iconic model of our hard-working, brick-and-mortar grandparents. As Davidson puts it, “We’ve inherited a sense of efficiency modeled on attention that is never pulled off track. ”

But these days, according to research, “the contemporary worker switches tasks an average of once every three minutes.” And at the same time, one teacher tells Davidson—which she mentions in the book—that at her school, 26 percent of children are diagnosed with a learning disorder. Such numbers help Davidson make her central argument about a mismatch.

“When we feel distracted, something’s up. Distraction is really another word for saying that something is new, strange or different. We should pay attention to that feeling… Distraction is one of the best tools for innovation we have at our disposal—for changing patterns of attention and beginning the process of learning new patterns.”

Davidson invites us to regard the sensation of being distracted—the thing so many of us are compulsively medicating ourselves to ward off—as a good thing, an opportunity to fix the mismatch between how we’ve automatically approached the task at hand and what the task at hand actually demands of us.

Davidson’s is a good perspective. It is nonjudgmental, and acknowledges that we are in the throes of a transition. For any one of us who has been panicking about how to adapt to constant, ubiquitous demands on our attention—how to achieve relevant, quality work, even as the workplace is shifting beneath our feet—it’s comforting to know that most people have yet to figure this out, and that it’s not a reflection on our natural capacities or intelligence.

Davidson doesn’t necessarily have answers for how to navigate our new, modern landscape. She tours innovative classrooms and describes the teaching methods she finds there. She visits companies that have implemented cutting-edge practices—including Wikipedia, IBM, and Specialisterne, the Danish software company that has built a hugely effective workforce by hiring employees with autism, a condition that pre-disposes them for success at their detail-oriented and highly repetitive job of checking digital coding. Specialisterne is a perfect example of “collaboration by difference,” one of the Internet-age ideals Davidson insists we must take on board.

For both school and work, Davidson enthusiastically advocates “gaming”—using various forms of video games for education and work. To my mind, this is the most dubious aspect of Davidson’s book. Then again, I was born before 1985, so I might be biased against the notion that I should be designing an avatar right now with which to make virtual conversation with my colleagues—or rather, their avatars.

Nevertheless, Davidson speaks to us from the center of the Zeitgeist. In clear terms, she presents the problems that are emanating from the chasm that’s opened up between our technological new lives and the old standards and routines we still feel obliged to pay attention to.