What Tip O’Neill knew about politics, and Alice Waters knows about produce, Rory Stewart knows about foreign interventions: Go Local! Moral imperatives and security concerns do sometimes justify or require war and intervention, but such actions should follow the vision set forth on the menus of so many hip Brooklyn restaurants: whenever possible, work with what grows locally.

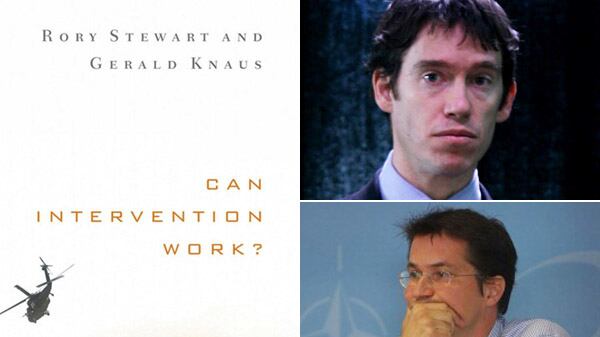

In two essays in their new book, Can Intervention Work?, Stewart and Gerald Knaus argue that a more humble, more nuanced, locally informed approach is needed to make foreign interventions successful. There are good reasons to listen to Stewart and Knaus, not only because of the accessibility and well-drawn nature of their essays, but also because of where they themselves have been on the ground.

Stewart’s American arrival was announced on the cover of The New York Times Book Review. He was pictured striding across an Afghan plain, an image taken during his 2002 trek across Afghanistan, the subject of his wildly popular and acclaimed book, The Places in Between. Since then, he has traversed the academic and political landscape, becoming a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government (where I enjoyed Stewart’s generous advice on Afghanistan on numerous occasions), the director of the Carr Center for Human Rights, and a Conservative Member of Parliament in London. Knaus, meanwhile, is the founding Chairman of the European Stability Initiative and an expert on the Balkan wars of the 1990s.

Gone, they suggest, should be the obsession with McKinsey-speak and its “best practices," “rule of law,” “efficiency,” and “transparency.” Some government-school speak can go as well, particularly the fixation with “governance,” “government,” and “failed-states.” Gone, above all else, should be the cookie-cutter, "one recipe works everywhere" approach to foreign wars and interventions. Such an approach, they argue, dooms certain interventions when they happen, and encourages them when they shouldn’t.

The international consultant should make way for the imperial locavore. He or she speaks not only languages but also local dialects, has knowledge not only of global commerce and national economies, but also of the micro-economies that differentiate even neighboring villages. The imperial locavore sees rules and stability where satellites see merely empty spaces, the uses of tradition and culture where moralists see backwardness. This new imperial agent, Stewart advises, understands that intervention is an art and the knowledge put to use a form of wisdom.

Stewart and Knaus are in no way alone in understanding that the success of interventions orchestrated by Washington and London are determined in local villages halfway around the world. Current counter-insurgency strategy places high value upon local-nationals (as they are known), most importantly in protecting their lives against insurgent attacks. Stewart and Knaus see more than lives requiring of protection, but political structures, public opinions, and legal traditions that should be heeded, respected, and harnessed. (Note to any potential invaders of Ames, Iowa—hold a straw poll as soon as you possibly can.) Here Stewart’s comparison of intervention to mountain rescue is especially helpful: it should be done only when absolutely necessary, and even then it should be understood that every situation is unique and possessing of unpredictable and uncontrollable factors.

Just how hard is it then, to get it right? There are reasons for optimism. Their book is peopled with admirable individuals. The people who pass through these pages are most frequently well-intentioned, smart, dedicated, and immensely hard working. Young military officers serve with valor, doing what they can for even younger Afghans, while diplomats such as the late Richard Holbrooke seek opinion, demand honesty, and pursue success with remarkable energy. Stewart points out the inevitable blind spots of NGO officials, journalists, and policy-makers, but only while also drawing attention to his own.

But good character and determination cannot overcome the wrong type of knowledge. Stewart quotes the Persian poet Rumi who was born in contemporary Afghanistan. “Oh how often have knowledge and keen wits and understandings/ Been as deadly as brigands or ghouls to the wayfarer.” This does not leave us nowhere, but it does leave us, rather as in Afghanistan, in somewhat of a tough spot. Success in Stewart and Knaus’s vision would seem to require officials on the ground possessing a remarkable range of knowledge, enabling them to recognize local needs and local structures, and to recognize the limits of what can and cannot be done.

How does one produce these imperial locavores? Forget junior year in Madrid, think a Ph.D. in Mazar-e-Sharif. How does one empower such individuals? Such a change, as they see it, would require institutional reform in the U.S. the U.K., and the United Nations. These are both tall orders, and they know it. Stewart has become one of the wise men of Afghanistan, his opinions and guidance sought by policymakers, academics, NGO officials, and writers. He has a unique perspective on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, informed by a view from the ground, from on high in the ivory tower, and from the halls of power in London and Washington. In a single month in 2008, according to his own estimate, he participated in 104 different meetings on Afghanistan around the world. Going local is a global sell—and a hard sell at that.

It is the habit when talking about empire—and that after all is what we’re talking about—to search for the apt imperial comparison: the Greeks and expansion, Rome and decline, the Mughals and religious plurality, Britain and sea power, and so on. And the idea of going local, as the authors well know, is nothing new. Before the liberal imperialism of the early-nineteenth century—and its efforts to produce, as Thomas Babington Macaulay famously put it, “a class of persons Indian in blood and colour but English in tastes, in opinion, in morals, and in intellect”—there were the so-called White Mughals of the late-eighteenth century, Britons who donned the costumes of the subcontinent, taking on its lifestyles and habits, and, frequently, its women. And, as the liberal reform efforts collapsed in the crisis of the 1857 Indian uprising, the British abandoned universal truths and models in favor of more local traditions and structures. The imperial officers in charge of such efforts often spent their lives serving in the Empire and decades on the ground in India.

But whereas these imperial officials may have brought with them not only knowledge but also the prejudices of race and class, these new men and women on the ground of whom Stewart speaks might bring sort of enlightened self awareness. He describes the grooming process: “The ideal education is through an ever more detailed study of history, the geography, and the anthropology of a particular place, on the one hand, and of the limitations and manias of the West, on the other.” Of course, as Stewart and Knaus point out, such localized experts now must be sought out not only for the existing wars, but also the presumptive responsibilities taken on in Libya.

Some would see such repeated intervention itself as the mania; but if you must climb that mountain—and sometimes you must—the lesson remains that you hope to bring a profound knowledge of local systems and a good dose of humility, because you have to know whether and when to turn around.