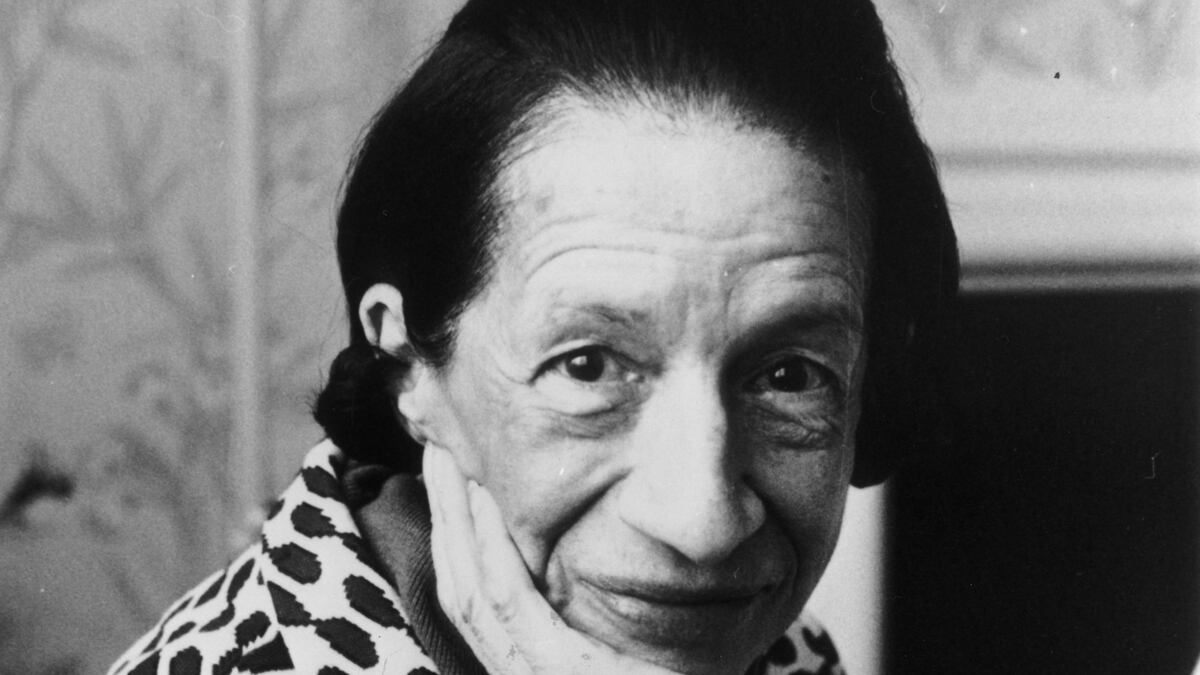

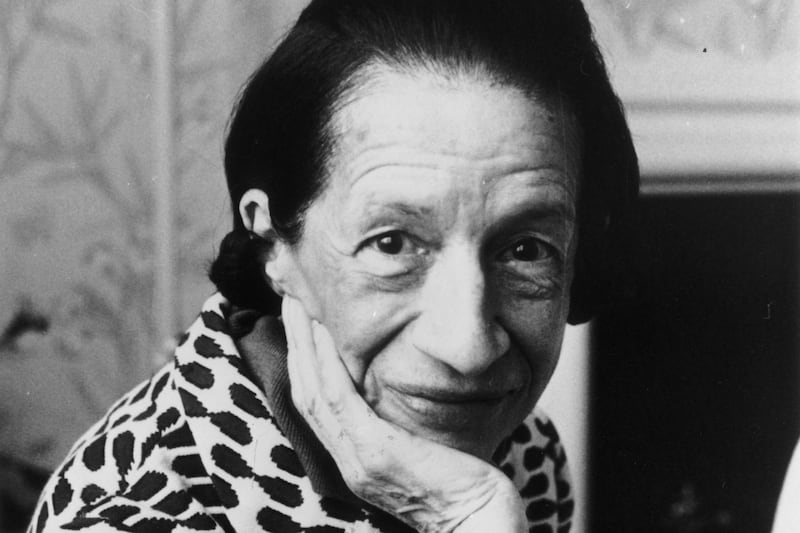

Diana Vreeland, the legendary editor of Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, was a woman in the right place at the right time. She came of age in Paris during the Belle Epoch, and remembered Diaghilev and Nijinsky dancing across her living room when she was a girl. She danced alongside Josephine Baker in Harlem during the Roaring ‘20s, rode horses with Buffalo Bill, frequented Coco Chanel’s atelier, witnessed the coronation of King Edward, saw Hitler at the Munich Opera, attended Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball, and kept a close friendship with the Kennedys during their first days in the White House. She was in New York during the swinging ‘60s—and a well-respected female editor during the years of Women’s Lib. “The first thing to do is to arrange to be born in Paris,” she once said. “After that, everything follows quite naturally.”

A new documentary, Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel, tells the story of Vreeland’s many adventures—which eventually led her to serve as fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar from 1937 to 1962 and editor-in-chief of Vogue from 1962 to 1971. The film, which premieres at the Venice Film Festival on Saturday and the Telluride Film Festival on Sunday, is, in a way, narrated by Vreeland herself: it is strung together on a series of conversations between Vreeland and George Plimpton, which they recorded while she wrote her autobiography, D.V. Their dialogue (which is reenacted by actors) is interspersed with video of Vreeland’s interviews with Dick Cavett and Diane Sawyer. More than 40 fashion-world stars, including Manolo Blahnik, Carolina Herrera, Franca Sozzani, Diane von Furstenberg, Anjelica Huston, and Calvin Klein, are interviewed about Vreeland on camera.

Above all, Vreeland was a woman of fantasy. In one scene, she recalls sitting outside her family home in Brewster, N.Y. and seeing Charles Lindbergh, aboard the Spirit of St. Louis, fly overhead. It’s a story that, yet again, puts her at the foreground of history—never mind the fact that Lindbergh’s route was nowhere near Brewster. “Do we know that Nijinsky danced through her living room?” asks the filmmaker, Lisa Immordino Vreeland. “We don’t. But it doesn’t matter, because she put us there. She keeps history in a totally different way.” Vreeland was a self-admitted believer in “faction”—the synergy between fact and fantasy. As she put it, “You’ve got to give people what they can’t get at home. You’ve got to take them somewhere.”

ADVERTISEMENT

This sense of fantasy was fundamental to the way Vreeland worked as an editor. She challenged propriety when she ushered in the bikini and blue jeans—“The most beautiful things you’ve ever seen”—and created fashion spreads so elaborate and expensive, they transported American readers into worlds not their own. “She had a taste for the extraordinary and the extreme,” Anjelica Huston says in the film. At Bazaar and Vogue, Vreeland both reacted to the world around her—and captured the zeitgeist of six decades on the pages of her magazines. “For the first time, youth went after life, instead of waiting for life to come to them,” Vreeland said about youth culture in the 1960s, which she captured in several spreads, including one called “Youth Quake.”

“Fantasy was like a pulse to her,” Vogue Fashion Director Tonne Goodman says of Vreeland in the film. “When she felt the pulse, it kept everything alive.” Vreeland discovered talents such as Twiggy and Lauren Bacall, and fostered the careers of Diane von Furstenberg, Manolo Blahnik, and Oscar de la Renta. She’s credited for embracing people’s “faults” by encouraging her photographers to emphasize a long neck or a space between a model’s teeth. “She saw things in people before they saw it in themselves,” von Furstenberg says.

After four decades in publishing, Vreeland eventually was fired from Vogue, because, as she says, “they wanted a different sort of magazine.” She found herself briefly adrift. “I was only 70. What was I supposed to do, retire?” She eventually was invited to become the creative consultant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, where she staged elaborate shows that brought traditional costumes to life. She painted the walls of the museum, carefully styled the mannequins and piped perfume into the galleries. With exhibits such as The World of Balenciaga and Yves Saint Laurent: 25 Years of Design,” Vreeland brought crowds into the Costume Institute—but clashed with the Met’s director over her unconventional approach to curating an exhibition. “She knew the history of fashion, but she didn’t get bogged down in it,” one colleague says of her life. “She was about ideas, and the magic of fashion” more than historical accuracy. To that end, Immordino Vreeland says, Vreeland would have loved the Costume Institute’s most recent (and most-attended) show, Savage Beauty, which focused on the work of Alexander McQueen. “She would have understood his kind of madness and creativity,” she says.

Immordino Vreeland, who is married to one of Vreeland’s grandsons, began the project while researching for a coffee table book on the late editor, which is due out in October. She realized the material was so rich that it deserved to be a documentary—and spent three years on the project. Among the 60 interviews she conducted for the film, Immordino Vreeland speaks with Vreeland’s two sons, who are candid about their mother’s lack of affection. And in one touching scene, Immordino Vreeland’s 9-year-old daughter reads her great-grandmother’s “Why Don’t You…” column, which became a staple during her pre-war years at Harper’s Bazaar. “Why don’t you paint a map of the world on all four walls of your boys’ rooms, so they don’t grow up with a provincial point of view?” the little girl asks. “Why don’t you wear velvet mittens with everything?”

Although Vreeland was known as the “Empress of Fashion,” to the world, Immordino Vreeland says she was “so much more than fashion. She created the fantasy in fashion.” It’s ironic, then that Immordino Vreeland and Diana Vreeland never met. “I’m not sure I could have pulled this off if I met her,” the filmmaker says. “I think she had this strength about her. And I think it would have been hard for me to interpret if I knew what it was.”

An exhibit dedicated to Vreeland will open at the Fortuny Museum in Venice in March.