That Awful Book, Part Two

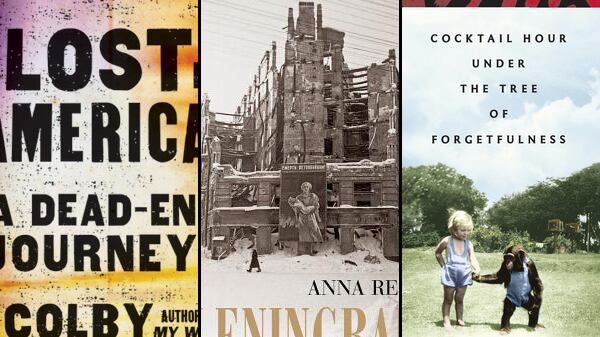

File this under The Things We’ll Do for Our Parents. Throughout her latest book, Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness, Alexandra Fuller makes frequent reference to her first memoir, the extraordinary Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, or as it is referred to in her parents’ household, That Awful Book. That debut memoir described the Fullers’ life as a white family in Africa when colonialism was in its last throes and being white was, at best, unfashionable and often dangerous. The Fullers persevered out of stubbornness, but more important out of an abiding love for their adopted continent. The parents, Tim and Nicola, were also terribly un-PC in many of their opinions—good people but on the wrong side of the fight—and their daughter never hesitated to make this plain in the Awful Book.

Cocktail Hour is a much sunnier book, constructed, as the title implies, as though it were told over drinks at day’s end, with a lot of “Do you remember that time when we ...” lead-ins to family anecdotes and stories. Fuller casts the narrative as a joint biography of her parents—how they wound up in Africa, the countries they lived in, how they got on—but the loveliest part is the generous way she steps back and lets them tell the story. Nicola, in particular, turns out to be exactly the sort of woman you’d travel halfway around the world to have a drink with—she’s as funny, often unintentionally, as she is tough: having costumed a protesting 8-year-old Alexandra for a Fancy Dress Party, she says, “There we go then. I’ll just get my Uzi and we’ll be off.” (The joke here is that she’s not joking.)

There is considerable darkness in this story as well, with the loss of children (drowning, childbirth) and the loss of beloved homes in country after country, as the Fullers move and adapt, though somehow managing to always keep true to who and what they are, a fact summed up in the irreducible list of possessions that accompany them: “dogs, Mum’s collections of books, the two hunting prints, linens, towels, the bronze cast of Wellington (now missing its stirrup leathers) and the Creuset pots.” But sorrow is always in context, a part of the story but not its central point.

Cocktail Hour's dominant theme is love—love for one’s family, love of adventure, and more than anything, love of place, a love that in the end unites the daughter with her mother and father—and woos the reader as well: “A single baboon in the cliffs barks a warning and the warm world feels leopard watched. A breeze picks up in the meadow and blows the cereal scents of grass and old heat-struck earth toward us. On an ordinary evening, we would have moved inside—a central African’s reflex against malarial mosquitoes—but on this inimitable night, none of us stir, the way no one gets up and leaves between movements at a concert.” Any parent who wouldn’t give just about anything to be the subject of such a book would have to be a pretty Awful Parent.

—Malcolm Jones is a senior writer for Newsweek and The Daily Beast.

______________________

Down and Out With the American Dream

“I don’t want to get stale. I don’t want to grow moss. I want to always be in a state of perpetual motion: going somewhere, doing something. If not, admittedly, I drink in my room and think of suicide. Not entirely healthy.”

So writes Colby Buzzell in his new book Lost in America: A Dead-End Journey, explaining his desire to pull a postmodern Kerouac and drive across the country, reverse manifest destiny style. Lost in America’s subtitle isn’t just a hyperbolic hook—this is an exploration of our nation at its most raw and browbeaten. There are a couple “time to shower” moments, particularly when Buzzell observes a pair of men in an abandoned plant submerging themselves into sewage muck for copper pipes that’ll pay their utility bills. From Salt Lake City to Cheyenne to Detroit, Buzzell encounters a Middle America down and out, chronically unemployed and holding on to past glories that aren’t coming back. Lost in America is decidedly not an inspiring book, but it is a defiant one.

The emotional catalysts that propel Buzzell on his road trip, and subsequently power Lost in America, are the recent death of his mother to cancer and birth of his first child. There’s a shameless element of escapism involved in Buzzell’s decision to drive across the country by himself, something he readily admits. Wrestling with the demons of real past failures and imagined future ones, he finds solace in the clarity of the present, one that demands nothing more than to “keep moving.”

Buzzell first shot to fame in 2005, with the publication of his combat memoir My War: Killing Time in Iraq. As in his first book, Buzzell’s prose is lean and deadpan. Unlike the episodic immediacy found in My War though, the long-term effects of Buzzell’s war experience resonate throughout this latest offering—he detests crowds, is proud of his military service while simultaneously trying to distance himself from it, and feels comfortable in a room only if he has full view of it from a corner. The firefights and IEDs of Mosul aren’t just still with him, they are actively a part of him; to his credit, he doesn’t seek sympathy or understanding for this, either from the reader or those he encounters during his travels. It simply is, like when he dons the uniform of a Salvation Army worker and finds it less fulfilling but more natural than when he used to don the uniform of a U.S. Army soldier.

Though spiritually inspired by Kerouac’s On the Road, Lost in America actually has more in common with another American road trip classic, John Steinbeck’s Travels With Charley. While Steinbeck journeyed with his loyal French poodle, Buzzell has only a 1964 Mercury Comet Caliente as a companion. Like Steinbeck, Buzzell doesn’t find much hope in the macro while crossing the continent, but rather is invigorated by the bold, unyielding resolve of individuals.

The Detroit chapters function as the backbone of Lost in America, with Buzzell staying there long enough to flesh out characters beyond the outlines and shadows that mark his other stops. There’s the indomitable Mrs. Harrington, who runs the small hotel he stays at and is determined to maintain her slice of order and cleanliness no matter what occurs outside the hotel’s walls. She serves as Buzzell’s surrogate mother and moral compass in a story of dystopian decay, even after he inadvertently upsets her by revealing he’s an atheist. And then there’s the bearded white apocalyptist who collects metal for a living on Detroit’s streets, melting the scrap down with a torch to turn it into fashion accessories: “I quickly got the impression that he was a bit of a misanthrope,” Buzzell writes. “He went on about how they’re pulling machines out of their factories and shipping them over to China, and we have a shrinking tax base … and how our economy will now be based on importing garbage from Canada and burying it.”

The pages of Lost in America soak themselves in whiskey shots and cigarette smoke, as Buzzell pursues the intoxicated underbelly of the various cities and towns he visits. The constant barroom philosophizing from the locals he meets gets tiring, but this hard-drinking, hardcore posturing isn’t just for show. Last spring, after meeting at a war writers’ symposium, Buzzell and I wandered the East Village on an impromptu pub crawl. On that night, he always seemed dissatisfied with where we were, and wanted to keep moving in pursuit of the literal and figurative “something else.” After ending up at the infamous Mars Bar (RIP) on hour six of our odyssey, I practically crawled outside for a taxi at two or so in the morning, desperate to get back home to Brooklyn. Buzzell, who’s built like a linebacker, looked at me incredulously, said “later on,” and turned to the overly pierced East Village weirdo on his left to chat him up for his life story. Whatever one thinks of Buzzell’s worldview and the means he uses to elicit opinions from the people he meets, just know it’s genuine—something bizarrely refreshing, despite all its grime.

When My War was first published, the late Kurt Vonnegut described it as “nothing less than the soul of an extremely interesting human being.” If he still lived, it seems likely he’d say the same after reading Lost in America. At the end of his bleak journey, Buzzell seems more at peace with the loss of his mother, and ready and willing to assume the responsibilities of fatherhood. How he gets there isn’t clean, direct, or all that uplifting. But it is real. And I can’t imagine a higher compliment for this master chronicler of human behavior.

—Matt Gallagher served in Iraq as an Army Cavalry officer. The author of Kaboom: Embracing the Suck in a Savage Little War, he is currently senior writing manager at Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America (IAVA).

______________________

The End of a Stalinist Fairy Tale

Four hundred grams of bread is approximately equivalent to one decently sized loaf. It is, if you’re eating dinner with friends, a fine introductory course, or if you’re preparing sandwiches for the family, a necessary ingredient. It is not, however, a suitable daily diet for an adult. To begin to understand the enormity of the societal collapse—the “fall down the funnel,” in the terminology of the time—that befell the citizens of Leningrad during the 900-day siege of the city by the Nazis, start with those 400 grams allotted by the Soviet authorities to the old, the infirm, and children. It was a slow form of starvation, death disguised as salvation. And it was only the beginning of the torment.

The perpetually paranoid Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin was said to have never trusted any man, with the lone exception of Adolf Hitler. So when Hitler unexpectedly invaded the Soviet Union in August 1941, Stalin was so taken aback that he initially refused to believe the rumors, even as the German Army moved ever deeper into Russia. By Sept. 24, the Nazis were less than 10 miles from the Hermitage museum, and in Britain George Orwell was picturing “Stalin in a little shop in Putney, selling samovars and doing Caucasian dances.” Museum employees were hastily evacuating the Hermitage’s treasures, removing paintings from their stretchers and hanging empty frames on the wall. Hitler, meanwhile, was having plans drawn up to raze Leningrad and Moscow to the ground, so as to avoid having to feed its hungry citizens.

Stalin and his henchmen, more interested in arresting Army officers and perceived malcontents than fighting back, were fatally slow in evacuating the city, leaving 3 million residents, including 1.1 million children and dependents, trapped when the noose finally tightened. “The Germans are at the gates, the Germans are about to enter the city,” an observer noted, “and we are busy arresting and deporting old women—lonely, defenceless, harmless people.”

Then, the siege ring closed, the residents of Leningrad were cut off from the rest of the Soviet Union, and the plot suddenly warps, from Band of Brothers to a real-life version of The Walking Dead. Families broke apart from the strain of hunger, people began to kill their own pets for food, and the new necessities of the siege were lanterns for light, stoves for warmth, and sleds to move goods, and dead bodies, through the snow-blanketed streets. Pavlov’s dogs were eaten. Women stopped menstruating, and men and women alike lost their sexual appetites. People began to suffer from a skin discoloration caused by hunger, casually known as “hunger tans.” And the terrible lack of food meant that some of the hungry inevitably turned to cannibalism in order to survive another day. If it weren’t for the unpleasant fact of its all being true, it would make for arresting science fiction.

Society was breaking down, with mass starvation marking the end of the fragile Soviet order. Anna Reid in her new history of the siege makes us feel the woozy, light-headed sensation of tumbling down the funnel ourselves, faced with the unbearable decisions that had to be made. Reid is intent on shattering the Soviet myths of the saintly, superhuman residents of besieged Leningrad (“wiping off the syrup,” in the words of one Russian historian), arguing that “far from standing apart from the ordinary Soviet experience, it reproduced it in concentrated miniature.” In her polite, impartial fashion, Reid decimates the Russian mythology of the Great Patriotic War, acknowledging the stories of poet Anna Akhmatova “standing guard duty outside the Sheremetyev Palace” and the (relatively) peaceable evacuation of women and children along the Ice Road while bearing witness to the silent horrors of the siege.

The true heroes, she ventures, were ordinary citizens like Ivan and Olga Zhilinsky, who protected a friend, even at the risk of their own lives: “They invited him to share wine and duranda at New Year—painstakingly cleaning their room and clothes beforehand, and giving him a wash and shave on arrival—took him in when his flat was made uninhabitable by shelling, and finally traded bread so as to give him a proper grave.” Doing their best to survive on their meager bread ration “supplemented with cough drops, glycerine, castor oil, wallpaper paste and carpenter’s glue, washed down with hot water flavoured with orange peel, mustard powder, blackcurrant twigs or salt,” Olga Zhilinsky died on March 20, 1942, and Ivan was arrested by Soviet authorities and convicted of “slandering Soviet reality.”

When spring came, the city’s terrible death toll, and easier access to goods, meant an end to the worst of the famine. The siege, though, would continue until 1944, and by the time the city was liberated, more than 750,000 people had died of starvation. The Soviet authorities honored survivors, even as the reality of their experiences was carefully elided. But the people who lived through the years of famine in Leningrad never forgot it, reminded of their suffering by a piece of stale bread they couldn’t throw out, or a stick of wood abandoned on the street. Now, thanks to Reid, we know something of what they endured.

But human language crumbles in the face of the Leningrad siege, simple words being too bluntly efficient to plumb the depths of the horror. How to describe a mother who “had smothered her eighteen-month-year-old daughter in order to feed herself and three older children”? Collecting firsthand testimony from diaries and letters, Reid tunnels into besieged Leningrad, stripping away the Stalinist fairy tales in order to reveal the unbearably stark landscape of a society torn free of all its moorings.

—Saul Austerlitz’s work has appeared in The Boston Globe, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and other publications.

______________________

Katey Kontent, the cool, nervy star of Amor Towles’s Rules of Civility, is the sort of girl who hangs out in churches after work. But not because she is religious. And certainly not because she is pious. Anonymity is the one thing that comes free in New York City, but Katey, having been raised in Brooklyn, is compelled to work a little harder to feel mysterious. As Towles writes in Civility, “the toughest thing about being born in New York City is the fact that you’ve got no New York to run away to.”

Towles’s debut follows Katey through her mid-20s, from an all girls’ boardinghouse, where Eve Ross spills a plate of noodles in her lap and becomes her best friend, to lavish parties in the Hamptons to the jazz clubs downtown and tiny coffee shops in the Financial District. The notion of a quarter-life crisis didn’t exist in 1938, the year Katey, at 25, made the decisions that would inform her future, and this is what Towles is most interested in: the inclination to visit a certain dive bar on New Year’s Eve, to crash that particular party, and to quit an awful job, even though she’s just been promoted, as she leaves her career ambitions to chance.

Rules of Civility is a love letter to these seemingly random choices that 20-somethings make, but it’s also a paean to the post-jazz age and the city itself. “For however inhospitable the wind, from this vantage point Manhattan was simply so improbable, so wonderful, so obviously full of promise—that you wanted to approach it for the rest of your life without ever quite arriving,” Katey observes. But she does arrive, and before long finds herself toiling under the editor in chief of Condé Nast’s newest glossy magazine, outwitting some of the city’s most manipulative, elegant movers-and-shakers in her spare time—several of whom are desperate to get her into bed, and some of whom succeed.

“Slurring is the cursive of speech,” Katey tells a drunken dinner-party companion one night. Towles’s sparking dialogue is filled with tiny gems like these, which wouldn’t sound out of place tripping from the razor sharp tongue of Gossip Girl’s Blair Waldorf. But the contemporary parallels don’t end there. In fact, Rules of Civility is infused with them, deliciously evoking both a New York that will never again be in tandem with a New York that is unchanging, whether the power players live in an Upper East Side brownstone or a Bedford Avenue railroad apartment. The year begins and ends with Katey’s musings on Theodore “Tinker” Grey, a blue-eyed banker whose obsession with a former president’s book of moral codes shapes both the frame of the novel and the star-crossed chase he embarks on with Katey and Eve, neither of whom cares as much about landing the hottie as they do about making a name for themselves. “I’m willing to be under anything,” Eve tells Katey conspiratorially at the beginning of the end of the Depression. “As long as it isn’t somebody’s thumb.” Rules of Civility is a judgment-free, glorious romp that casts an egalitarian light on elegant and cruel social climbers; poor but pretentious artists and shy, quirky millionaires whose lives organically intersect in the only city where such a thing has always been possible.

—Sharon Steel