Ten-year-old Shiloh Johnson lay in a hospital bed for 43 days as medical tubes protruding from her chest slowly drained suffocating fluid from her heart and lungs. Each day brought a new challenge, many of them life-threatening.

Her veins went flat, requiring nurses to insert an IV. Her kidneys went into failure, requiring dialysis. She suffered cardiac arrest and had to be revived. For three weeks she slipped into a coma, unaware that her mother was sitting alongside her day and night, in utter disbelief that a simple trip through a restaurant buffet line could wreak such havoc on her healthy, vibrant child.

Shiloh and several hundred others who ate at a restaurant in Locust Grove, Okla., back in 2008 were the victims of a virulent E. coli bacterium known as 0111, one of six strains that food-safety experts say are increasingly appearing in meats and other foods across the globe.

Despite the bacteria’s devastating effects in outbreaks from Oklahoma to Japan, the Obama administration took more than two years to officially recognize the six strains as something dangerous that should be screened by federal meat inspectors. Salmonella—which can cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea and which is common in poultry and meat—also has routinely escaped monitoring by federal meat inspectors. An antibiotic-resistant form of salmonella was at the center of a massive recall of turkey meat this summer.

Monday’s decision to regulate the six E. coli strains comes after years of efforts by food-safety advocates like attorney Bill Marler, who celebrated the announcement: “I am more than a little pleased.” But there is much more to be done. “Food safety is one of the things you can’t rest on; government has done its responsibility and now industry has to step up.” He says he has a strong suspicion—and hope—that meat inspectors “will start looking at antibiotic-resistant salmonella in the same way.”

If so, it could be another long haul in a system that remains challenged by limited budgets and manpower. The industry wants a different approach. “The USDA will spend millions of dollars testing for these strains instead of using those limited resources toward preventive strategies that are far more effective in ensuring food safety,” says James H. Hodges, executive vice president of the American Meat Institute.

The industry has long insisted that more testing isn’t the answer and will only add to consumer costs. The administration, which has won accolades for enacting some recent food-safety reforms, says it hopes to continue closing holes in the safety net but worries that a Congress hellbent on reducing the deficit may undercut those efforts with budget cuts starting next year.

Rep. John Dingell (D-Mich.), a longtime siren inside Congress about weaknesses in America’s food-safety-surveillance system, remains convinced that “a lot more people are going to have a bellyache and die” before things get better.

Until Monday’s announcement, federal meat inspectors were required to check for only one E. coli strain, known as 0157. The food-safety agency inside the U.S. Agriculture Department recommended in January—two years after Shiloh’s illness, and more than a year after Marler petioned it—that the six strains be added to the screening list.

The delay in changing our food-safety requirements is just one of several potential weaknesses identified by a Newsweek investigation of America’s safety net against food poisoning and bioterrorism. That review found:

• The two agencies on the front lines of food safety, the Agriculture Department and the Food and Drug Administration, have different risk assessments, legal standards, and resources committed to the effort. • USDA inspectors admit they are stretched so thin that they frequently miss required inspections at some plants, particularly in the populous Northeast. • FDA inspectors physically check only about 1 percent of the food shipped into the United States from foreign countries and get to only about a quarter of domestic plants a year. • The administration is considering permitting raw-meat imports from Brazil, a country that has struggled with foot-and-mouth disease and various strains of E. coli for years and whose inspection system for pathogens—in particular E. coli 0157—has been flagged as weak by the USDA in a recent audit.

This was supposed to be the year that food safety took center stage in Washington. After coming to office, President Obama created the Food Safety Working Group, and in January he signed into law the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act, the first major overhaul of the Food and Drug Administration’s food-safety responsibilities since the 1930s, approved with broad bipartisan support.

But the euphoria of that success has given way to widespread fears that any gains will be undone by budget cuts expected as part of the deficit-reduction deal struck in August. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the new law will cost $1.4 billion to implement, and the Senate Appropriations Committee budget has proposed maintaining food-safety funding, but House budget versions would cut the FDA by $241 million and the USDA’s meat-inspection program by $88 million. Even the president has suggested cutting the USDA’s meat-inspection program by $9 million in 2012.

There’s little dispute about the scope of the threat. The CDC estimates that some 128,000 Americans are hospitalized and 3,000 die each year after eating contaminated food products. It says some 112,000 cases of food poisoning each year are linked to the E. coli strains that will only now begin to face regulation.

Meanwhile, serious outbreaks abound across the globe:

• Cargill issued one of the largest recalls of meat in U.S. history this summer after an antibiotic-resistant salmonella was found in its ground turkey. • At least 53 people in Europe were killed and more than 4,000 sickened this spring in an E. coli outbreak linked to sprouted seeds from Egypt. • Last summer, an outbreak of E. coli 026 in Maine and New York sickened only three people but surprised scientists by its appearance in ground beef.• A 2010 outbreak of E. coli 0145 in several states was traced to likely RV toilet dumping on romaine-lettuce fields, the first such produce-associated E. coli 0145 outbreak in U.S. history.

The outbreaks are only part of the worry. Occasional U.S. intelligence reports in recent years have warned that terrorist organizations have contemplated poisoning food as a means of attacking Westerners.

The FDA, responsible for screening for pathogens in fruits, vegetables, dairy products, and foreign imports, employs about 1,800 inspectors (more than in years past, but still not enough, say food-safety advocates, to meet inspection needs), just sufficient to inspect a quarter of their intended domestic plants one time each year. That means some facilities go years without an inspection, a 2010 HHS report found. At the border, FDA inspectors use electronic screening and risk analysis but physically inspect only about 1 percent of food imports, officials say, a number that leaves advocates at watchdog groups like Food & Water Watch stunned.

Unlike its counterpart, the FDA has long considered any illness-causing strain of E. coli to be illegal and can block any shipment of food it finds tainted by a pathogen. The problem, however, is that its inspections are infrequent, and many times come with a forewarning that allows plants to prepare in advance.

“We always knew before the inspectors came. The only random test would be of the first company they got to,” says Laura Dean, who worked for Mott’s and other food companies for years before becoming a whistleblower with the Government Accountability Project.

The second half of America’s defense is the Agriculture Department’s meat inspectors—8,000 strong, a relatively stable number over the years—who are supposed to inspect meat-packing and -processing plants every day as part of a system that gives the USDA’s seal of approval to meats sold in stores.

But several USDA inspectors told Newsweek they are short-staffed, particularly in the populous Northeast, and often skip required daily visits to plants because they run out of time.

“If you’re going to be asked to cover three, five, six, eight plants a day, you are overworked. The agency says we spend 2.5 hours each day in plants, but if you’re talking five plants a day, that just doesn’t add up,” says Stanley Painter, a Food Safety and Inspection Service consumer-safety inspector in Alabama who spoke to Newsweek in his role as chairman of the National Joint Council of Food Inspection Locals.

Painter says the agency is in denial about the risks inherent in the current system. “This agency has never been or is willing now to admit failure,” he says, a sentiment echoed by other inspectors interviewed by Newsweek.

An FSIS spokesman says the agency has an aggressive recruiting system and that “regardless of our vacancy rate, we maintain a staffing structure to ensure that FSIS is able to meet its statutory mandates and to protect the public health.” He said that as of December 2010 the overall national vacancy rate for slaughterhouse inspection positions was 1.84 percent and that the rate for public-health veterinarians has declined from 11.5 to 7.7 percent. With budget cuts proposed by Obama among others, attorney Marler suggests, “having an inspector in every meat-processing plant is expensive. If we want to cut, it does have an impact on how inspections are now performed. Perhaps money can be saved if an inspector was assigned multiple plants and visited unannounced and frequently.”

For now, however, the new E. coli regulations have been heralded as a significant step, even among hardworking inspectors. Will they add much too much to inspectors’ workloads? “Not a lot, and what it does add is worth it, in my opinion,” says Trent Berhow, speaking in his position as the inspector union’s joint council vice chairman, currently headquartered at a hog plant in Iowa. But new computer duties and a limited number of inspectors often lead to delayed work. “If I have an inspector absent I’m frequently pulled onto the assembly line, and then my job goes undone,” Berhow says.

USDA inspectors also have no legal power to order a recall. They must bargain with the packaging plants where problems are found, with their primary leverage being the ability to pull inspectors from the plant and withhold their good-housekeeping seal.

The inspectors’ haphazard powers are the outgrowth of years of political influence leveraged by the meat-packaging industry and agriculture interests on Congress. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, major agricultural interests contributed more than $20 million to federal candidates in the last two elections. Says attorney Marler: “The problem is not with the inspectors per se; the problem is with the political influence the meat industry has on Congress that then pressures the agency.”

The industry argues that increased screening won’t make things much better but could raise costs to consumers. That’s an especially cogent threat during lean economic times.

“You can’t test your way to food safety,” says Betsy Booren, the director of scientific affairs for the American Meat Institute Foundation, which represents the lion’s share of red-meat and poultry companies in America. “The best way is through preventative measures.”

Salmonella screening poses its own challenges, the industry notes. Mike Martin, a spokesman for Cargill, says there are some 2,400 strains of salmonella. As a result, the USDA admits that if it could test every bit of ground turkey produced in sample sizes, it would expect some 49.9 percent of portions to be positive for salmonella, and it allows for that.

“To get to zero is a real challenge,” Martin says. “If we did nothing but testing for salmonella and non-0157s, there wouldn’t be anything left to eat.”

Meanwhile, food-safety advocates are watching to see if the White House is able to fend off the budget cuts, and they say that while there are good rules and hardworking inspectors in the system, there is still much to be done. When it comes to making our choices in the grocery aisle, we’re all exposed to the benefits but also the risks of our food-safety net, says David Theno, a microbiologist and food-safety expert.

“We’re all standing there side by side, just hoping somebody did the right thing.”

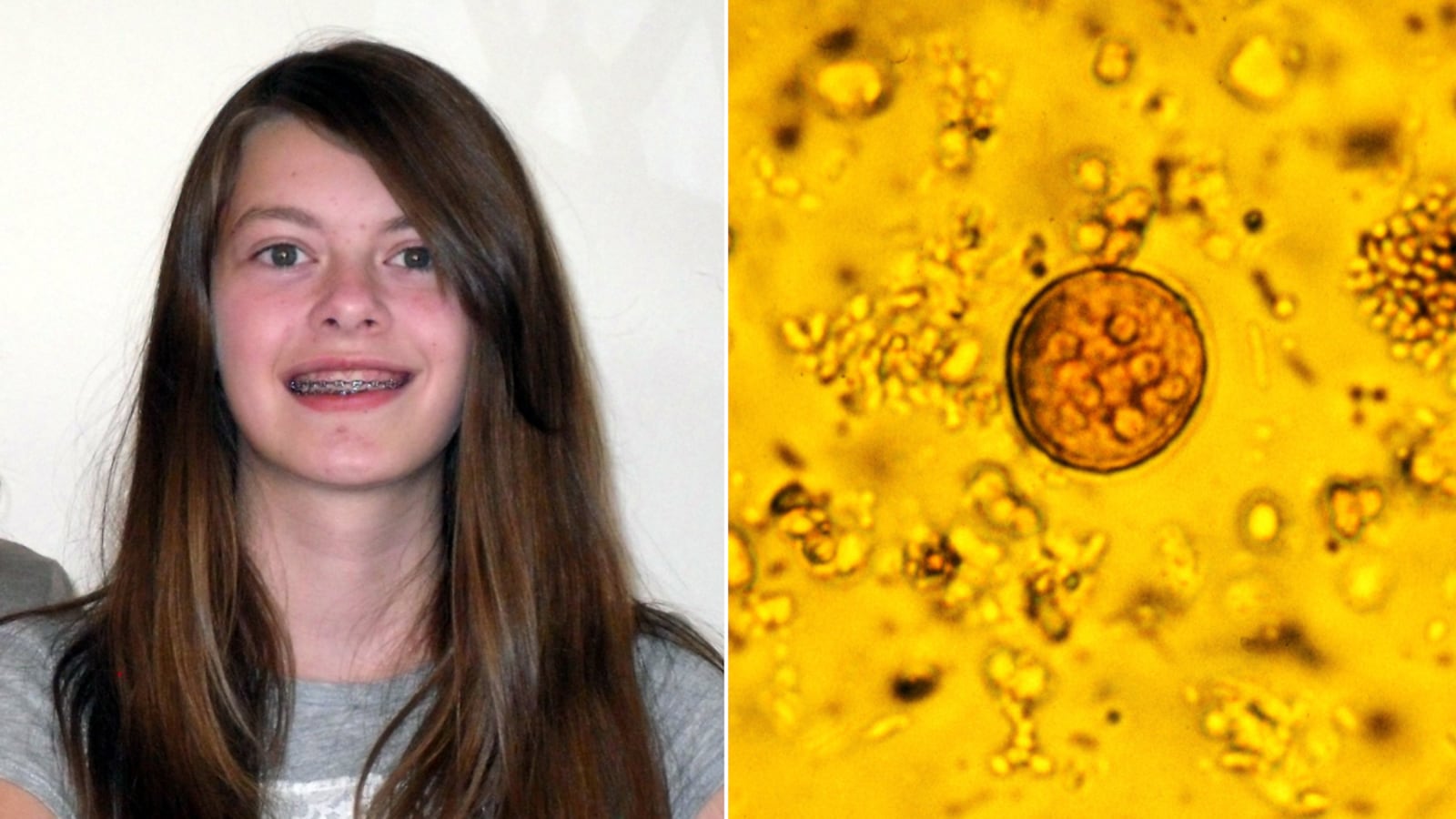

Parents who have lost their children to various strains of E. coli share a heart-crushing awe at the speed and ruthlessness of the illness. Iowa mom Dana Boner watched her daughter, Kayla, whither away after eating food tainted with E. coli 0111, a strain that only this week was belatedly made illegal to distribute in meat.

Kayla—a star athlete—began getting sick on her 14th birthday, and was hospitalized two days later. “My only thought was how to tell her ‘Sweetheart, you probably won’t play basketball this season,’ not that she would die,” Boner recalls. Within a week, Kayla’s kidneys began shutting down, she was put on dialysis and continued to vomit profusely. She was profoundly embarrassed, says her mom, as any teen would be by the uncontrollable diarrhea. “Sorry for keeping you up all night mom. I love you,” Kayla told her mother. One hour after saying those words, she had a seizure and was put on a ventilator, tears in her eyes and a tube stuck down her throat. “That was the last thing she ever said to me,” her mother says. Soon, Kayla would suffer a heart attack and die.Boner contrasts the quick death of her daughter to the years-long process it took to get the new E. coli strains regulated. “If my child had been killed by a gun we’d be looking for the killer,” she said. Now, thanks to the Obama administration’s decision Monday, the killer strain will soon be screened.