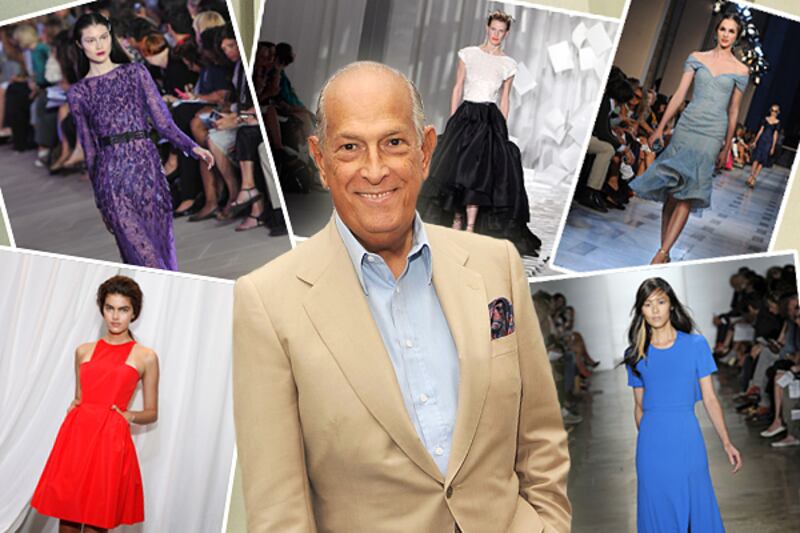

As the Spring 2012 runway shows unfold in New York, younger designers continue to dominate the schedule as the fashion industry experiences its own version of a baby boom. While those designers claim a variety of inspirations, from the California landscape to notions as ethereal as “air” and “action,” one éminence grise has had an outsize influence on the current aesthetics: Oscar de la Renta.

His singular sensibility has informed an entire generation of designers. Its ubiquity in their work is drowning out other voices, blunting fashion’s capacity to empower and equating dressing up with being grown-up.

The elegant and charming 79-year-old has held sway among socially prominent women for decades. Born in the Dominican Republic, the New York–based designer speaks eloquently, using a vocabulary of feminine ruffles, polished silhouettes, joyful colors and embellishments. While he certainly can cut a fine day suit—the likes of which have been particularly favored by Hillary Clinton—he is most highly regarded for his ability to create clothes for the cocktail hour and beyond.

De la Renta has realized inaugural ball gowns for both Laura Bush and Clinton. Jenna Bush was married in one of his creations. And one of his party dresses served as a plot point in the pop-culture juggernaut Sex and the City. If de la Renta has a singular skill, it is his ability to make women—both young and old—look their prettiest. And it is this skill—not necessarily his technical expertise or his personal familiarity with how a certain generation and class of women live—that seems to have captured the imagination of his followers.

Younger designers such as Jason Wu, Prabal Gurung, Peter Som, and Zac Posen seem most interested in dressing a kind of rarefied woman, a fashion butterfly who lives an idealized life rather than one filled with hurdles and hard work. She may be accomplished, but her clothes do not speak of power and authority, ease and confidence. Instead, they suggest a woman who wouldn’t quite know what to do if she happened to be caught without an umbrella and a driver in a rainstorm.

In the eyes of these designers, this woman is more of a damsel than a dame.

Designers commonly riff on history in search of inspiration. Sometimes they bring out the femme fatale who uses her sexuality like a weapon. Or perhaps they embrace the 1960s and 1970s and the rise of the liberated woman. Or they offer a take on the 1950s through the character of the sexy—and quietly controlling—secretary. There is a kind of power, authority, and irony in all of that retro iconography that keeps it grounded in contemporary times. This Oscar obsession is different. It isn’t a riff; it isn’t a cheeky homage. It is an earnest belief in a 1980s opulence that translates into an aesthetic of social isolationism. This isn’t a style that places a woman into the center of our cultural times; it sets her apart from her own era.

“Many of these designers weren’t around during Reaganomics. This is all new for them. For them, it’s the distant past,” says Patricia Mears, deputy director of The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology. “For me, they’re taking it too literally.”

Few of these young men are moved by the group of elders who saw fashion as something empowering—those designers who helped to create today’s modern vernacular of power dressing, strong femininity, or even athletic physicality. The bold minimalism of Calvin Klein doesn’t speak to them. The gray flannel and banker pinstripes of Ralph Lauren do not seem to have made an impression. There is little evidence of the swaggering tailoring of Bill Blass, none of the impassioned sensuality of Donna Karan.

“In the new world of fashion, you find two camps: fast fashion and designers who understand that an affluent woman wants to look like a woman,” says Ken Downing, fashion director of Neiman Marcus.

So what do these designers think a woman should look like in 2012?

She is swathed in color. She is embellished with feathers and baubles. She is accessorized and polished. She is precious, primped, cinched, and controlled. It is exhausting just to look at. Her style is uneasy and self-conscious. She often looks like she’s playing dress-up.

There’s also something decidedly anti-modernist about this group. For while they may refer to “craftsmanship” as their motivating force, they’ve made the decision to apply that skill and expertise to a trussed-up, spit-shined, doll-like woman from another era.

“They’re looking past their own generation. I can’t imagine a 20-something wearing these clothes. In some ways, I guess that’s refreshing: They ‘re not dressing someone who’s 19 but someone who’s 60,” Mears says.

But why are they so captivated, muses Mears. “Is it culture? Gender? No young women are designing that way,” she notes.

Indeed, female designers, both newcomers and veterans, have no use for this kind of Barbie-doll perfection. Doori Chung—inspired by the illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley and trained by modernist Geoffrey Beene—looks decidedly forward with her draped white shirtdresses and loose-limbed blazers and light-as-air skirts. Victoria Beckham’s slim-fitting dresses in blocks of navy and searing orange are as sleek and aerodynamic as a modern sports car. Tess Giberson deconstructs her knits until they are little more than fragile strands, turning them into a kind of abstract art. Nicole Miller turned to pop art, skateboard culture, and street style for her inspiration. Tracy Reese’s Blanche DuBois gowns and juke-joint strapless dresses might be retro in nature, but they are never precious and rarefied.

The Row, by Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen, was a study in modern elegance with its easy-fitting trousers and blazers, airy tunics in ivory and sea foam, and an ivory evening caftan with silver embellishment. And Diane von Furstenberg showed one of her most captivating and energizing collections in quite some time, filled with dynamic prints, draped silhouettes, loose-fitting pullovers, and a kind of easy sexuality that is both powerful and irresistible.

It makes one wonder: With whom are these young male designers spending their free time? Who are the women who might whisper in their ears? What kind of street theater is unfolding in front of them?

The designer Wes Gordon showed his collection Thursday evening in one of the many loft spaces on the city’s far west side. Gordon—a tall, dark-haired Georgia native—is only 25 years old and was presenting his fourth collection. He apprenticed under both de la Renta and Tom Ford. But of those two fashion parents, the one with the greater influence is de la Renta. There is very little of Ford’s signature sex appeal or hedonism.

Gordon created a beautiful line for spring. It is filled with ivory lace boleros, rococo printed skirts and tops, and ribbon-embroidered jackets. The clothes are upscale and pretty. And one needed to look no further than to his mother, who was in attendance, for proof that he knows how to cut a suit to fit a real woman.

Still, the way in which the clothes were styled, with their spindly sandals and a sweet fragility that was almost breakable, one had to wonder: has greater equality in schools, sports, work, life made these young male designers freer to create clothes that are in some cases almost oppressively, stereotypically girly?

Designers Gurung, Wu, Som, and Posen envision—in varying degrees—a kind of uptown, high-maintenance, chauffeur-driven woman whose fashion life seems exhausting but who also gives off the whiff of helplessness.

Wu certainly can craft a magical moment with silk faille coats, feather-embellished skirts, and embroidered dresses. And for spring, he paired many of his lavish jackets with shorts, giving them a more youthful exuberance. But once a woman steps outside Wu’s carefully controlled world and onto the street, she looks a bit like a glass figurine who has somehow escaped the safety of her snow globe.

After Wu’s show, one guest made her way down to the nearest avenue—her jet-beaded bolero twinkling in the afternoon sun—in search of a cab. Her needle-thin heels wobbled on the uneven pavement. She seemed so vulnerable. Clothes don’t always have to be armor, but these seemed to leave her painfully exposed.

Som has always blended polish with an eccentric sense of color and pattern. And his collection for spring, as with so many other designers, was dominated by bold prints. But one can’t help but compare the work he does for his own label—so composed and effortful—with the consulting work he does at Tommy Hilfiger, where the color and edge he’s injected into the preppy label is far more organic and fun.

It may be that what is so distracting and disconcerting about the work of these young male designers is that their clothes often come across as self-conscious. They have embraced an aesthetic that they admire. But it doesn’t seem to be what they inherently know—how could it be when the world is so casual, freewheeling, and fast-paced?

Posen’s collection was almost entirely form-fitting cocktail suits and a seemingly endless stream of elaborate, fanciful ball gowns. They were beautiful pieces, but who will wear them? When? Why?

As Ken Downing of Neiman Marcus noted, women who have the means to buy designer clothes want something that is special. They want to look feminine. But there are a lot of ways to look like a woman while also celebrating the promise of the future rather than meditating on the way life used to be.

It isn’t necessary to go the way of Alexander Wang with his relentless attachment to a dark, disheveled street prowler—one who carries around a Brobdingnagian leather knapsack.

One of the most beautiful collections came from designer Derek Lam, who was inspired by the modernist landscape of California. His models wore a leather trench in a bright geranium red, ivory and red honey-comb knits, tank dresses dripping in paillettes, slim navy trousers cuffed in ivory, and short-sleeve dresses in leather and nubby linen.

Lam’s clothes were expertly executed. His models looked feminine and pretty. Most important, they looked confident, capable—and sturdy enough to deal with a rainstorm all by themselves.