When I set out to write a memoir called It’s Hard Not to Hate You, about embracing toxic emotions and giving myself permission to be an unrepentant rageholic, I knew I had to include a chapter on professional jealousy. Nothing flared my freudeschaden—taking misery in another person’s joy—like New York Times bestselling debut novelists.

The rich. The thin. The beautiful. I’ve got no problem with them. If the world’s wealthiest, hottest woman walked into my office and asked for a cup of coffee, I’d get it. But if she said, “Guess what? My first novel just hit the New York Times bestsellers list!”?

Hate. She could get her coffee in hell.

My first novel was published (with a whimper) in 1991. I’ve written two dozen books since. Most landed with a thud, but some did well enough to eke out another contract. Critically, I’ve earned stellar—and horrific—reviews. I’ve won an award, and been nominated for others. My books have been translated into dozens of languages. And yet, I’m as anonymous an author as Gertrude M. Sneedermann. Who? Never heard of her?

Exactly.

I’ve never made it—“it” being, as any author could tell you, The New York Times bestseller list. When I started out, I fantasized about striking it big. I still do. Dreams of literary stardom didn’t die or fade away. They limped along, dragging tirelessly, like a zombie.

I was fortunate that writing itself wasn’t painful for me, as it was for many of my friends. I loved filling blank pages. Writing was easy. Making a living at it was hard. Making “it” was damn near impossible.

* * *

A first-time novelist sent me a manuscript and asked me to “blurb” her, or supply a quote for the cover. I read it, blurbed it, felt smug in my benevolence and a trifle worried how the author would react when her debut failed to catch fire. A few months later, the book came out, became an instant megahit, a NYT bestseller, readers lapping up more copies in a single week than my last five novels combined, which, granted, wasn’t much.

This exact scenario has happened to me four times.

When it did, I felt a little sorry for myself. Blurbing flops was easier on the ego. I didn’t hate the authors per se. I hated the cosmos that allowed anyone to have so much so fast. I hated the guilt and shame of my jealousy. I should be thankful for my modest success. And I was! But, on some days, gratitude was trampled by jealousy and, worse, doubt. I might lack the talent, skill, depth, understanding of human nature and luck to connect with a large number of readers in a meaningful way.

My next-door neighbor, a famous shrink, once asked me what my professional goals were. I said, “To write a bestselling novel.”

She said, “I once dreamed about that. But then I decided it was too shallow a goal.”

Shallow! She was calling my name.

My bestseller dreams weren’t entirely ego and money driven, though. Entertaining people, linking lives, contributing to the culture via the written word were noble goals. It was the ambition of any novelist to get a reaction, and not just write furiously into a vacuum. Despite 20 years of cycling between expectation and disappointment, I hump along with that aim in mind. Deluded? We all do what we can to get through the night.

Maybe if “it” happened, the freudeschaden would stop. I asked the most successful person I knew if she still felt professional jealousy. “All the time!” said Joan Rivers, American Icon. “Anyone who says they’re not jealous is turning a blind eye to their true emotions—or lying. When friends call to say, ‘I just got a TV show,’ I say, ‘I’m so f------ jealous, I’m going to kill myself.’ That’s my way of congratulating them. You have to say out loud that you’re jealous to keep it from taking over. Pretending it’s not there makes it more powerful.”

Bowing to her wisdom, I spent a month outing my freudeschaden to family and friends. One said, “That’s it? Jealousy is your secret shame? Jesus, I thought you had a body buried somewhere.” Most admitted that they, too, hated nearly everyone of equal age and ability who’d topped them. Joan was right. Talking about jealousy really took the edge off. If I’d known that years ago . . . all the clumps of hair and bitter tears I’d needlessly sacrificed. What a waste.

* * *

The chapter on professional jealousy is the centerpiece of It’s Hard Not to Hate You, a memoir I’m proud of and hopeful about. In an emotionally detoxed state of mind, I began work on the next book, which, ironically, led to my becoming—by proxy—the very creature I so despised: a NYT bestselling debut novelist.

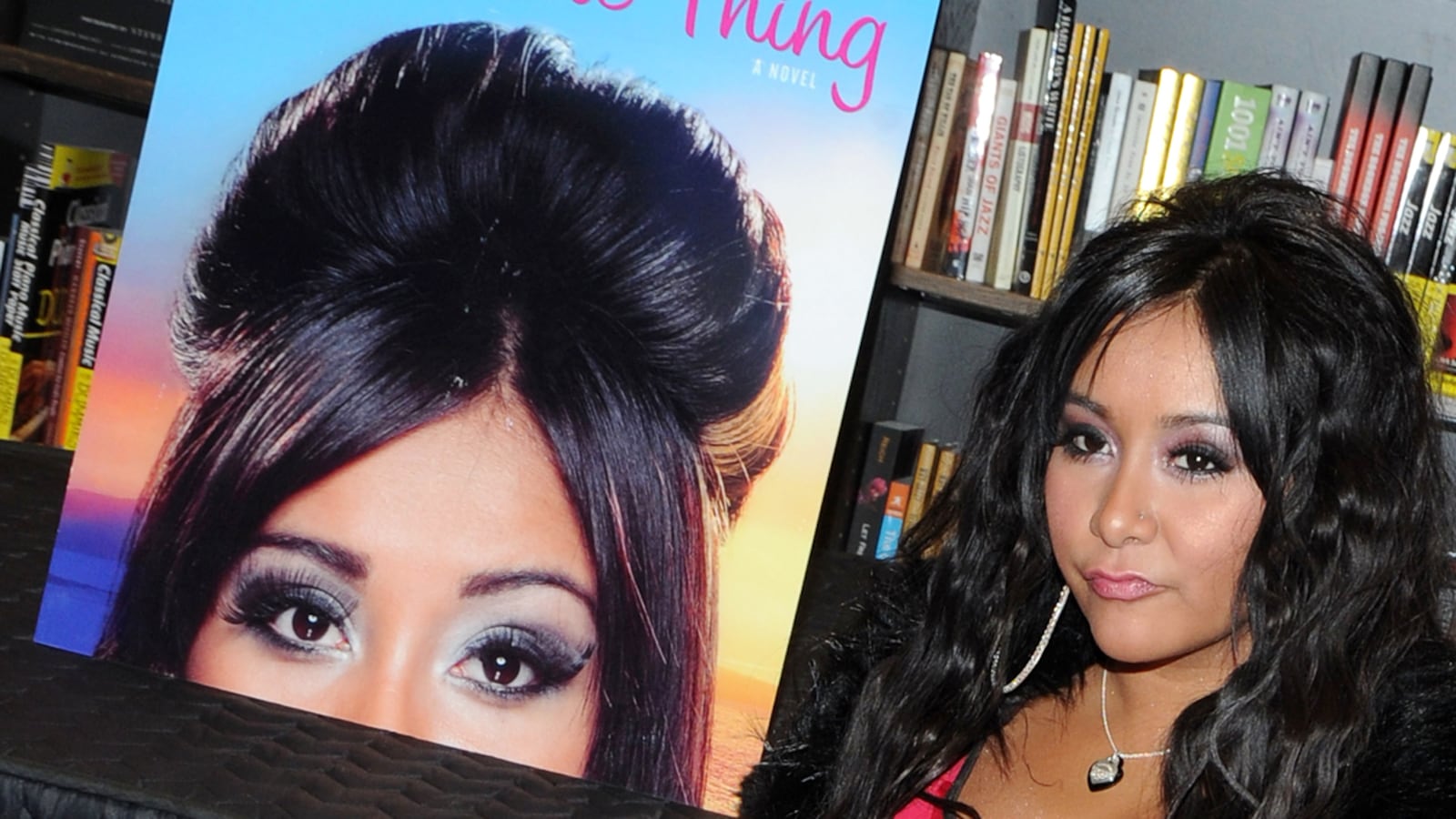

Time travel? Mushrooms? No, the feat was accomplished by the raw star power of Snooki. I collaborated with Nicole Polizzi on her beach romance, A Shore Thing. Although my name isn’t on the cover, Snooki gave me plenty of credit. When Matt Lauer mentioned my name on the Today show, I squealed. Her fans loved the book. Literary types universally loathed it. They called it a sign of the apocalypse, the death of publishing, etc. On Twitter, Jodi Picoult called its release “the end of the world.” If it’d been up to me, I would’ve put that blurb in 20-point type on the paperback edition:

“The end of the world.”—Jodi Picoult

I sympathized and related to the hate. For two decades, the hater was me. I’d lived in the struggle to get attention for my work, to elicit a passionate reaction, to contribute to the culture, even the lowbrow, via the written word. To finally break out of the vacuum was, as Snooki might say, friggin’ awesome. The glory might be shallow and small. But I loved every minute of it.