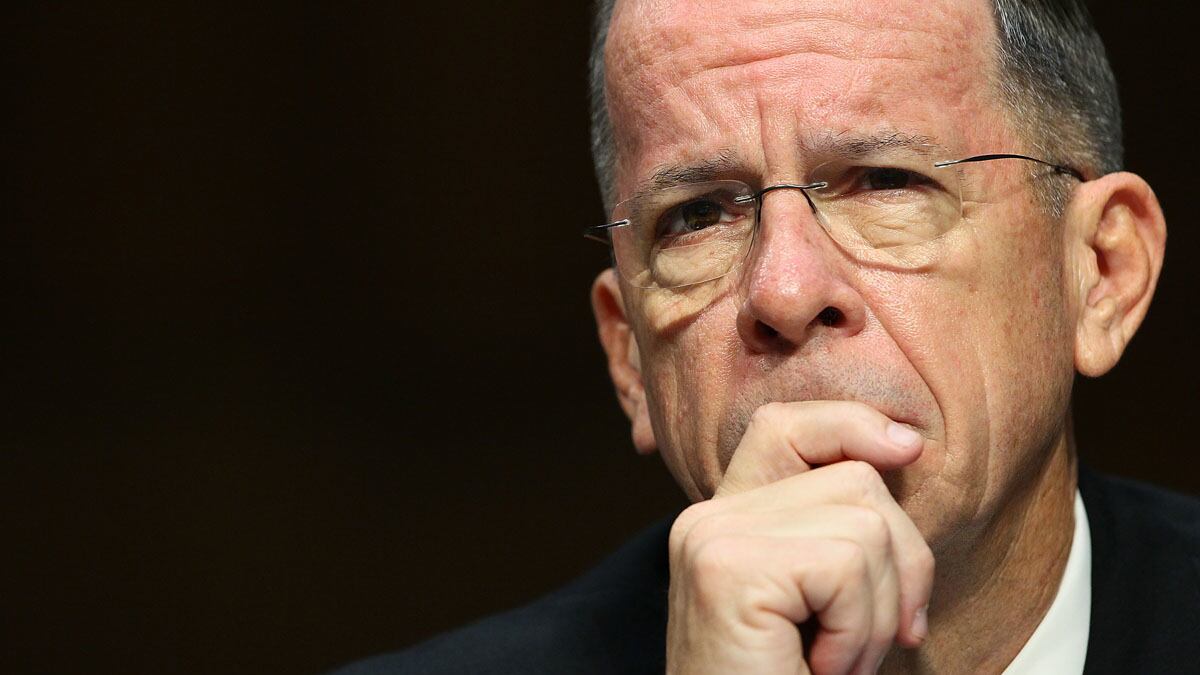

The media have been giving big play to yesterday’s accusation by Adm. Mike Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, that the Haqqani network, accused of masterminding the assassination last week of former Afghan president Burhanuddin Rabbani, “acts as a veritable arm of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Agency,” the feared ISI. Rabbani was murdered by a suicide bomber pretending to be a Taliban negotiator. Pakistan, of course, has issued a stinging denial of involvement. But the Obama administration is unlikely to have made the charge lightly, and the accusations, if true, provide more evidence of ISI’s continued complicity in terror attacks, both inside and outside the Afghan theater.

The question is why anyone would be surprised. It is not as though this is the first administration warning about ISI; or even the first from Admiral Mullen. Put aside the lingering belief that elements of Pakistani intelligence shielded Osama bin Laden as he implemented his hide-in-plain-sight strategy in the city of Abbottabad, less than a mile from the Pakistan Military Academy. The ISI’s history is longer, and grimmer—and no secret.

Just this past February, testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee, Admiral Mullen answered a question from Sen. John McCain by warning that Pakistan “on the political side ... looks worse than it has in a long time.” Mullen added that lots of terror groups, not just al Qaeda, make their headquarters there. At the same hearing, then-defense secretary Robert Gates quoted Mullen as calling Pakistan “the epicenter of world terrorism.”

And at the focal point of the epicenter sits the ISI. Most Americans probably had never heard of the group until allegations came to light that some of its people might have hidden bin Laden. But the ISI has long been accused of being an overt actor, not just a passive partner, in terror operations. India believes that the group has been an integral part of terror attacks within its borders. Britain has long suspected the ISI of involvement in the London underground attacks in the summer of 2005. And the Rabbani assassination is hardly the first time the ISI has been suspected of providing logistical and other support to terror attacks in Afghanistan. When Afghan security forces foiled an assassination attempt on President Hamid Karzai three years ago, they blamed the ISI.

In April of this year, shortly before the killing of Osama bin Laden by American special forces, Mullen traveled to Pakistan, hoping to urge the ISI to crack down on those within its ranks who support the Haqqani network. After the death of bin Laden, the United States tried again. But the ISI has no history of listening. Even as the overt side of the Pakistani military seems more determined than ever to cooperate, with some 140,000 troops along the Afghan border, the ISI seems more determined than ever to continue its ways. True, ISI has helped the United States capture some of its most-wanted terror suspects. But the harm the group now does seems to outweigh any positive contribution to the terror war.

Why, then, does the ISI do what it does? Former National Security Council adviser Shamila N. Chaudhary, in a valuable essay for Foreign Policy, argues that Pakistan wants to remind America that it is an indispensable partner in peacemaking efforts in Afghanistan, and that the insurgency will continue as long as Pakistani power brokers find it useful.

“The reality on the ground,” writes Chaudhary, “indicates that Pakistan’s patience with the United States has also run out.” Pakistan, she says, believes it is the scapegoat for America’s own failure to win decisive victory in its war with the Taliban. ISI’s nefarious activities, then, might be a way of reminding the United States that Pakistan, whatever its faults, is a necessary strategic partner if negotiations are ever to succeed.

Both the administration and congressional leaders seem silently to accept this hard reality, because there is little serious talk of punishing Pakistan. After bin Laden was killed, and Pakistan blustered unpersuasively that no one in its government had an idea where he was hiding, there were calls in Congress to reduce military and humanitarian aid, or even to cut it off entirely, but they faded with time and probably were never seriously meant. It has always been one of the strange and unkind truths of international diplomacy that you must deal with all sorts of countries. If you decide to take as allies only well-behaved liberal democracies, you will not get very much done in the world.

This does not mean that the Obama administration should not continue to press Islamabad to rein in the terror networks with which its intelligence agencies enjoy such intimate relations. We simply have to recognize that our long-term strategic interests are not altered by the horrific terror attacks and assassinations that make headlines. (Indeed, in one of the ironies common to the region, the ISI itself turns out to be, in a sense, our own unruly stepchild. The agency had fallen into desuetude during the 1970s. Its current robust air stems largely from its rebuilding, with American support, during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.)

As the administration begins implementation of its troop draw downs from the Afghanistan theater, the involvement of ISI with terror groups may not even be the biggest long-term strategic problem in the region. Let us not forget, for example, that the Taliban, despite everything, has not been defeated and, as General Petraeus said in Senate testimony earlier this year, would love to get its hands back on Afghanistan.

But the most serious challenge, barely remarked upon by the media, is the growing influence throughout the theater of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Iran operates a huge madrassa in Kabul, and its flow of low-cost goods across the border has been a great boon for Afghan consumers, who have suffered through a long series of oppressions and wars. Yet it also flexes its muscles when it chooses, as in the decision last winter to blockade desperately needed fuel deliveries to its neighbor. The West, with its typical myopia, barely noticed; but Iran’s leaders were clearly signaling to their neighbor that “we will be here long after the Americans are gone.” And the Islamic Republic is still widely suspected of complicity in the January acid attack on Afghan journalist Razaq Mamoon, who has written scathingly about Iran’s efforts to destabilize his country.

The United States has been, for the past decade, the most important power in the region. The forthcoming American withdrawal will leave a power vacuum, one that Afghanistan’s neighbors will be only too happy to fill. Afghanistan is likely to be left with a central government too weak to defeat the Taliban. The only sure path to avoiding domination by Pakistan, and its Taliban clients, might be to look to its more powerful neighbors in Tehran.

That is a dangerous choice to leave behind as we declare victory: an Afghanistan run by the Taliban or an Afghanistan that is a satellite of Iran. Neither would be good for our national security interests, and both would be disastrous for the people of Afghanistan.