All Connected

“Barnes”—that’s the English novelist, Julian—“heads Booker short list as Barry”—the Irish novelist Sebastian—“left out.” So read a headline in a recent edition of the Irish Times. Not to worry. Sebastian Barry’s achievement, enhanced by his latest novel, On Canaan’s Side, may be too great to be defined by the Booker or any other literary prize.

Barry, the greatest prose writer in Irish letters—which by definition makes him the greatest writer of prose in the English language—has fashioned a body of work consisting of five novels, a compact volume of plays, and three slim volumes of poetry that is unique in Irish, British, or American literature. Practically all Barry’s characters are related by blood or marriage. The obvious comparison is to Faulkner’s Snopes family novels, but Faulkner wrote about them in just a single literary medium, prose fiction. His most famous characters all lived in one county; Barry’s are assigned by fate to lost corners of different countries.

The cornerstone of Barry’s work is his great play, The Steward of Christendom, the story of Thomas Dunne, a senior officer for the Dublin police who faithfully served the interests of the British crown for decades. Officer Dunne spent his declining years in the alien world of postrevolutionary Ireland, forever baffled that a life given to service had gone so unappreciated. His youngest daughter, Lilly, recalls him “as the enemy of the new Ireland, or whatever Ireland is now, even if I do not know what that country might be.”

His son, Willie (whose story is told in the novel A Long Long Way) died unmourned by his country while serving the British Army in France during the Great War. One daughter, Annie, stays in the old country to tend to Da; Lilly falls in love with a Black and Tan under death sentence by the IRA. They flee to the New World, where she is dazzled by New York: “I almost laugh at the memory of Dublin, with its low houses, their roofs tipped like deferential hats to the imperious rain.” More than 60 years later, having learned that the sins of the Old World are not so easily left behind, Lilly, like other Barry characters, writes a secret memoir to try to put the amazing circumstances of her life into some order, telling “our own little stories, without importance.”

“I am writing it,” she tells us, “and I spill it all out on my lap like very money, like riches, beyond the dreams of avarice.”

“Willie Dunne,” she writes, recalling the brother whose picture adorns her room on Long Island, “a lost name in the history of the world.” But one whose fate seems to haunt both Lilly’s son and grandson, who volunteer for American wars. Lilly is an astonishing creature, utterly plain and transparent but more resilient than even Yeats knew when he wrote “too long a sacrifice can make a stone of the heart.”

The past few years have seen a light industry of great fiction by Irish writers on America—Colm Toibin’s Brooklyn and Roddy Doyle’s Barrytown trilogy come quickly to mind—and wouldn’t it be grand if their characters met up somewhere and compared stories? But no one on either side of the Atlantic has constructed an oeuvre quite like Barry’s, with so many characters so connected and yet separated by time and space. Lilly, alone in America for many years, nonetheless “senses in my sisters a huge loneliness, each in her own way ...” The reader feels the irony with a stab: we know her sister’s loneliness better than Lilly if we’ve read her story, Annie Dunne.

No other novelist now writing can convey as Barry does the way in which unrighted wrongs continue to reverberate down through the ages, creating new versions of old tragedies for people with no knowledge of their origins. Barry is no kind of a political writer, and it’s doubtful that one reader in thousands who picks up his books, even in Ireland, knows or cares about the ruined lives of the Irish who supported the British Empire and lost.

On Canaan’s Side fits seamlessly into Barry’s unique and expanding vision, seeking to restore with language that which has been taken away by time. Its real subject isn’t politics or even history but memory, a memory which reveals that “a measure of tragedy is stitched into everything if you follow the thread long through.”

—Allen Barra

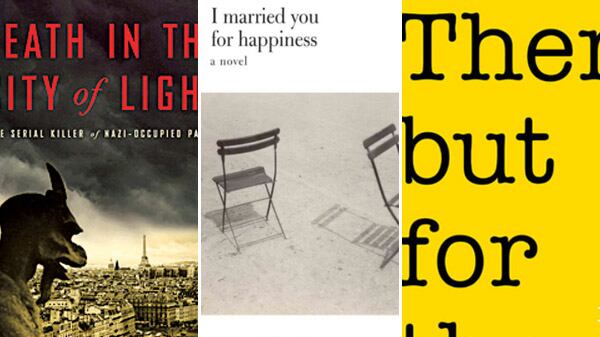

On the Prowl in Paris

In France before World War II, a doctor named Marcel Petiot was elected mayor of his small town. A few years later, he bested his competitors and grabbed a coveted national assembly seat. Petiot was a rising star in provincial politics. He was also a psychopath.

As historian David King writes in Death in the City of Light: The Serial Killer of Nazi-Occupied Paris, much of Petiot’s life seems to have been devoted to thievery, animal torture, drug dealing, and apparent witness removal (he’d often run afoul of the law, but those who were about to testify against him had a habit of vanishing). And in terms of his criminal career, these were just his formative years.

King’s book tells how a family physician and small-time public official used the Nazi occupation of Paris as a means of feeding his homicidal hungers. A statistical footnote when compared to the larger-scale atrocities of the 1930s and ‘40s, Petiot’s tale is nonetheless shocking. Rendered here in encyclopedic detail, it’s a story of almost incomprehensible madness, a uniquely disturbing chapter in wartime history.

With Hitler’s men clearing the city of Jews and others deemed unworthy, countless desperate citizens were seeking a way out of Paris. Posing as a member of the Resistance, Petiot let it be known that he was well connected, and that for a hefty fee he would arrange transportation and secure a new identity for those looking to flee to South America. But instead of finding freedom, King writes, Petiot’s clients were lured to 21 rue le Sueur, an “empty house near the Arc de Triomphe,” where they were murdered and dismembered.

Petiot lived elsewhere, using the rue le Sueur residence for the sole purpose of killing and disposing of his victims. The building caught fire in March 1944, and it was then that police discovered what he’d been up to. Because Petiot would prove a self-mythologizing egotist, it’s impossible to say just how many lives he took, but the number of strangers’ possession he kept in storage suggests the scope of his crimes. “The contents of the suitcases would prove remarkable,” King writes. “Inside, in no apparent order, were a total of 79 dresses, 26 skirts, 42 blouses, 48 scarves, 52 nightgowns” and scores of other items, among them more than 300 handkerchiefs and almost 80 pairs of gloves.

Finally captured seven months after police first learned of his crimes, Petiot was tried in 1946, and though he took responsibility for many deaths, he said his victims were Nazis and others who’d collaborated with the siege of Paris. These were the rantings of a fearful man, for in fact, as King notes, Petiot largely preyed upon Jews and others who were fleeing from Hitler’s enforcers.

The book spends a lot of time in the courtroom—almost 100 pages—but the trial seems to have been a genuine spectacle. At one point, Petiot kissed the hand of a female observer; throughout, he clearly delighted in sparring with prosecutors and court officials. “Indeed,” King writes, “in recounting the introductory overview of Petiot’s life, (the head trial judge) had only gotten to the defendant’s work as a student at the University of Paris, which he called ‘mediocre,’ when Petiot interrupted: ‘I did however get "very good" on my thesis.'” His “very good” marks didn’t spare Petiot from the guillotine.

Death in the City of Light might remind readers of Erik Larson’s 2003 bestseller The Devil in the White City. Like Larson, who told a story of serial murder set against a backdrop of Chicago’s 1893 World’s Fair, King backlights his primary tale with a pair of supporting narratives—one focuses on the hellish nature of Nazi rule, the other offers a social history of the Resistance as fueled by Parisian intellectuals. Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Charles de Gaulle, Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Simone de Beauvoir, and other giants of the arts and politics make memorable appearances in King’s richly reported and engagingly written book. Sartre, King notes, “compared the occupied city to ‘empty bottles of wine displayed in the windows of shops which could no longer manage to stock the real thing.’”

In focusing on Petiot, however, King presents the reader with a genuine puzzle—one that retains several of its mysteries to this day. For instance, the exact method by which Petiot carried out the murders remains unclear. Another ambiguity is just how much his family knew about Petiot’s hidden life as a killer. “Petiot,” the author writes, “did indeed take many of his secrets with him.” But King provides more than a few answers.

—Kevin Canfield

Must Read Aloud

One night in the middle of a Greenwich dinner party one of the guests goes upstairs and locks himself in the spare bedroom. Everyone assumes he is in the bathroom (awkward though his timing is, as the dessert brûlées need torching immediately prior to being served and he’s taking his time), but, when he fails to return and the bathroom is eventually found empty, the conclusion is drawn that he has simply gone home. It isn’t until the following morning—with the discovery of his car still in the resident’s parking space (“already ticketed”)—that his hosts realize his bad manners have, on the contrary, manifested in quite the opposite way: he’s still in their house. His reluctant landlords are left with no choice but to accept their “Unwelcome Tenant,” slipping him “flat packs of wafer-paper-thin-turkey and ham” under the bedroom door. (Their only act of defiance in the face of otherwise complete helplessness—their unwelcome squatter’s one and only communication having been a note that read “Fine for water but will need food soon. Vegetarian, as you know. Thank you for your patience.”)

Meanwhile, outside the house crowds are gathering. Everyone from journalists looking for a story to lost souls searching for the meaning of life all wait and watch with baited breath: “Did he want to know what it felt like to not be in the world? […] Was it some wanky kind of middle-class game about how we’re all prisoners […] Did he inhabit his cell for the good of others, like a bee or a monk? Or was he, say, a smoker and it was all an elaborate ruse to make himself give up?” In desperation the homeowners appeal to Anna for help; a woman whose email address they find in his abandoned phone.

Anna’s is the first of four viewpoints through which the rest of the story is told. Hers is followed by that of Mark, a man haunted by his crude dead mother whose “most recent attention-getting device was rhyme” (“I hate to be reminding you again / that writers are not fucking always men”); May Young, a woman who, despite her surname, is now finally “old”; and lastly, Brooke Bayoude, an inquisitive child with a penchant for puns and a way with words (“Oh my God, Caroline says. Had anything …happened to her? You know, anything (she nods towards the child)—bad? That’s the thing. It didn’t seem to have, Hannah said. But she didn’t know. She couldn’t know for sure. Had anything good happened to her? The child says”). It is with this word play, repetition, rhyme, and rhythm that Smith proves herself one of the “cleverist”—a British author at the top of her game who combines eccentricity and originality in equal measure. And, as I discovered when I heard her reading from the opening pages last week with a cadence rarely found in a fiction writer, There But For The is a story quite literally crying out to be heard. Here we have a novel, and a novelist, delighting in the joy of language itself.

—Lucy Scholes

Memories of a Marriage

Lily Tuck won the 2004 National Book Award for The News from Paraguay, a historical novel in which Ella, an adventuresome Irish-born courtesan catches the eye of Franco, a future dictator, while riding in the Bois de Boulogne, and accompanies him home to Paraguay. Franco is cruel, capricious, and a dunce at statecraft (he declares war simultaneously on Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay). The novel intersperses Ella’s diary entries with a series of elegantly polished vignettes of life in late-19th-century Paraguay to create a vivid, corrupt, and sensual world.

Tuck’s new novel, I Married You for Happiness, is a more intimate drama, but no less kaleidoscopic.

Tuck sets the scene poignantly with her opening line—“His hand is growing cold; still she holds it”—and then follows Nina’s musings in the hours after she discovers Philip, her husband of 42 years, dead in their bed.

Tuck’s moving narrative mostly inhabits the spacious realm of memory, as Nina, shocked into the realization that their life together is over, revisits the past. She sits by Philip’s side through the long night in shock, drinking wine, her mind skittering from the mundane (“Who will mow the lawn?”) to the profound (“Lies of awful omission … Should she tell him? In the dark room, she tries to make out Philip’s features. Can he hear her?”)

In intense compressed scenes, Tuck evokes a long marriage, beginning with the couple’s first meeting at a Paris café (Philip thinks Nina, chic in a men’s leather bomber jacket, a yellow silk scarf, and boots, is French). Nina gives equal weight to the milestones (their rainy-day wedding shortly after the Bay of Pigs invasion, their daughter’s conception and birth, their rocky year in Berkeley, when Philip develops a suspiciously close friendship with a fellow mathematician named Lorna, numerous summer visits to Belle-Île, where one year Nina has a secret lover), and the quotidian remnants (Philip’s “old-fashioned, scuffed-up, lace-up brown oxfords,” the “decrepit rowing machine in the basement” she has been lobbying to throw out).

As an intriguing counterpoint to the love story, Tuck weaves in an ongoing dialogue between Philip, a confident mathematician and professor who is expert at explaining such abstractions as the law of small numbers and theories of probability, and Nina, a painter with an artist’s impressionistic sensibility, attuned to “the vibrations and tremors of feelings on the threshold of consciousness.” In one witty scene, Nina’s urge to paint Philip in the nude is thwarted when he insists on wearing his red boxer shorts. She adds a Gauloise Bleue.

I Married You for Love is a poetic and absorbing novel; the final passages, as dawn breaks in this new widow’s life, are a rare and elegant affirmation of the transcendence of love.

—Jane Ciabattari