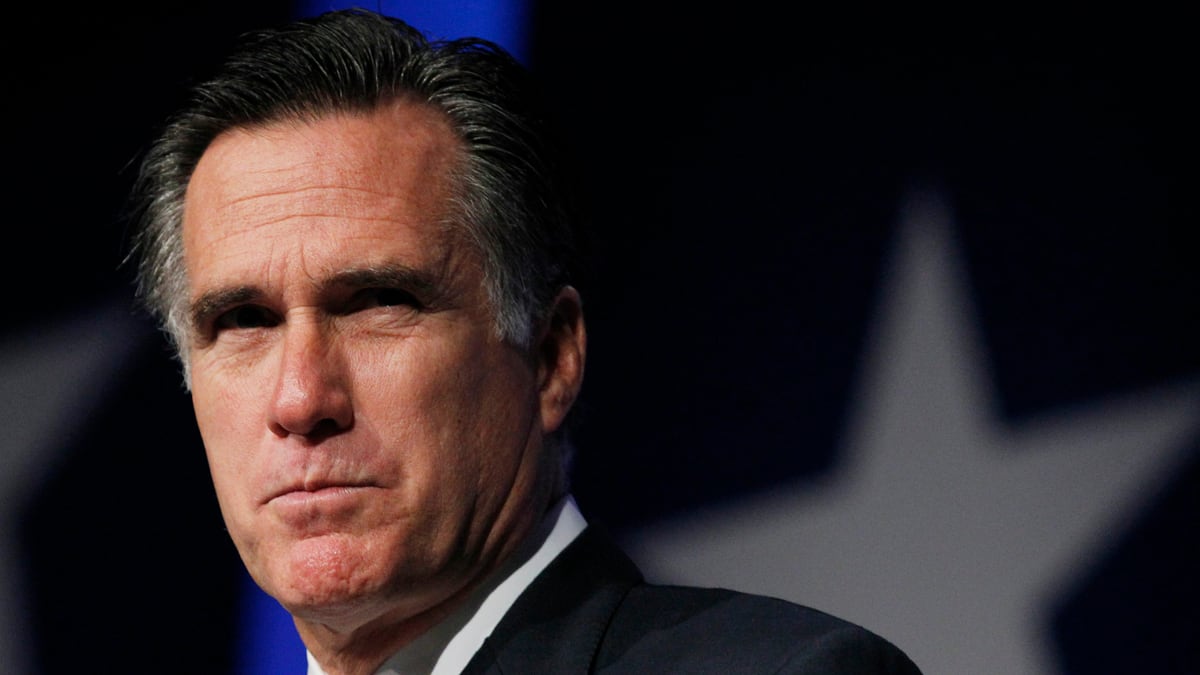

Mitt Romney can’t quite shake the Mormon question. My Daily Beast colleague McKay Coppins obtained some emails from a Perry evangelical adviser to a “leader in the development of Christian talk radio” showing that at least some within the Perry camp want to keep the issue, as they say, alive. The New York Times reported lengthily Sunday on Romney’s years as bishop of the Boston LDS temple. Christopher Hitchens has now declaimed on Mormonism’s “weird and sinister” belief system (rather tame adjectives, for Hitch). Is all this fair? Or, as Romney and his backers have it, is it religious bigotry? I’m not an expert on religion. But I do think I know a thing or two about politics, and from a nakedly political perspective, Romney definitely has a couple of questions to answer. Religious bigotry has nothing to do with it.

Let’s begin with the obvious background. In 1960—121 years after Joseph Smith had an audience with President Martin Van Buren to lay before him the case for action against the persecution of his flock—John F. Kennedy famously established the idea in his Houston speech that there should be no religious test for the presidency. I support this. We all should.

But confusion has arisen in more recent years about what this should and should not mean. It should mean that a candidate’s faith (or theoretical lack of same, although no one admitting to that will get within several area codes of the White House, which is itself another disquieting matter) is not a priori disqualifying. If Mitt Romney wants to believe that Jesus Christ visited a Hebraic civilization in Central America after his resurrection, he is entitled to that belief, and it has little to no connection to how he might make decisions in the Oval Office.

It should not mean, however, that all questions about a candidate’s belief system are automatically out of bounds. This is true whether that candidate be LDS or Jewish or Catholic or any kind of Protestant, or for that matter Bahai. Let us say we had a Southern Baptist—or, to make it less freighted, a Methodist or Lutheran—candidate for president who believed (say, according to something he’d written before he contemplated the presidency) that Jonah really did live inside that whale’s belly for three days and three nights. Incidentally, my hypothetical candidate could indeed be a Muslim, because the Jonah story is also retailed in the Koran.

Would it not be reasonable for us to ask our candidate whether he still believed that? And on what basis? Yes, it is a question that gets right to the heart of our culture wars. The Clarence Darrow-William Jennings Bryan exchange would be exhumed and feverishly relitigated. But it would be entirely fair for “us”—us, the media, and by extension the (I hope) strong majority that does not treat that parable literally—to ask whether the candidate held the story to be literally true. For a sizeable number of Americans, even religious ones who are not literalists, this would be problematic. This, you’ll notice, has nothing to do with whether the religion in question is weird or sinister or even a “cult.” It has to do with the specific candidate’s specific relationship to a specific story.

These questions arose, a bit, and to my mind entirely fairly and not forcefully enough, in 2008, with regard to a certain vice-presidential candidate. Evidence came forth that she was at least an interested fellow-traveler in a school of thought that posited man and dinosaur as contemporaries (read about the Taylor Trail for more). It strikes me as fair that Sarah Palin should have been made to answer this question. If she so believed, it didn’t necessarily cast dark shadows over the question of how she might interpret the Constitution. But it clearly would have cast those shadows over the question of her general judgment and probity. Fair—and useful for an electorate to know. (Fortunately, the electorate sensed the more general problem without it being asked.)

So, Romney. I’ve long thought that if one of the campaign beat reporters really wanted to put him on the spot, the obvious question would be: Do you really think the Garden of Eden was in Missouri? For my part, I doubt the Garden of Eden existed anywhere, except maybe in London in the Swinging ‘60s if you knew the right people, so I consider Missouri only a marginally less plausible candidate than wherever it was supposed to be (which is in fact open to question). But something tells me that most of my fellow Americans have rather firmer views about the matter. Now, I gather that adherence to this literal view, held by Joseph Smith, is not for Mormons today a doctrinal matter. But this is LDS teaching. I’d like to know if Romney believes this plainly absurd thing—even if you embrace every syllable of the Old Testament, logic says you have to put it somewhere “over there.” And I don’t think that’s remotely a bigoted position to take.

Romney could actually perform a service for himself, his candidacy, and his religion by doing what JFK did. Instead of hiding behind Kennedy in a superficial way and braying about bigotry, he could, you know, do what Kennedy did: Give a serious speech in which he discusses his religion seriously, tells us what he does and does not believe, explains LDS doctrine, elucidates his views on church and state, and makes clear (as JFK did) that as president he will serve earthly powers. Needless to say, he will not, which reflects both a weakness in Romney and a problem of our politics these days. The weakness in Romney is his superficiality, and the problem in our politics is... well, its superficiality.

He would not only neutralize these questions, but he would be performing a service for the principle Kennedy upheld half a century ago, instead of trying to cling to it cheaply like a life saver. And he should give the speech—in Missouri.