It’s a story the art world has etched in stone. After Stalin died in 1953, the frozen Soviet Union saw Khrushchev’s Thaw. Artists and intellectuals found themselves suddenly uncensored, which catalyzed an unprecedented period of creative experimentation. But following the humiliation of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Khrushchev refroze Soviet culture. Denounced artists sat in their rooms and produced art as an act of resistance. Eventually they were exiled, and found recognition and respect in America instead.

This standard narrative has served Ilya Kabakov, the godfather of Russian Conceptual art, particularly well. As a creator of ambitious “total installations,” he has become Russia’s most expensive and sought-after artist. His most famous works, like The Man Who Flew Into Space from His Apartment, created in 1984, were read as anti-Soviet manifestos. Even subtle drawings made early in his career brought him into conflict with the authorities—and thus launched his fame. For the first time, these drawings are being exhibited in the United States, in a show called The Study of Kabakov, at Edelman Arts in New York through Dec. 23.

But, for Kabakov, the true story of his life’s work doesn’t quite match the narrative that’s been constructed for Soviet-era artists.

“If you go looking for political meaning you can always find it. If you don’t, you don’t,” said Emilia Kabakov, a formidable artist in her own right who’s collaborated with Ilya since the ‘90s, and who happens to be married to him. Her husband does not speak English well, and Emilia helps him point out how scholars have appropriated his art to justify their views. “If you think about it, any work you want you can give any political meaning.” The misunderstandings happened early and often.

Kabakov was born in 1933 in the Ukrainian city of Dnipropetrovsk. He studied at the Art Institute in Moscow and became a book illustrator, working for the state. In 1965, his Shower series was exhibited in Italy and ran afoul of the Soviet authorities. The drawings show a man standing under a showerhead, but the water that comes out of it never touches him. Critics claimed the work symbolized the lack of material resources in the communist regime, and they ordained Kabakov as the voice of the anti-Soviet generation. But Kabakov preferred a view closer to Samuel Beckett’s, saying that he simply painted a person who’s forever waiting. He was thinking a lot about existentialism at the time.

The publicity made it hard for Kabakov to get work through the state. He began to retreat into his “unofficial” art. In the ‘70s he created oddball “personages” who tell their tales through paper drawings stacked up into “albums,” which became his famous 10 Characters series. (The pictures make up the heart of the New York show.) In one album, a boy named Primakov won’t get out of a closet. In another, the bureaucrat Maligin is afraid of standing out. The decisively Conceptual step was taken when Kabakov represented these quirks in visual ways: the Primakov illustrations are mostly black, since he’s hiding in the dark, and Maligin only draws along the edges, since he’s afraid to venture to the center. The new show plunks down on the table three of the 10 Characters albums. Viewers can dig into them, as long as they wear flimsy white cotton gloves.

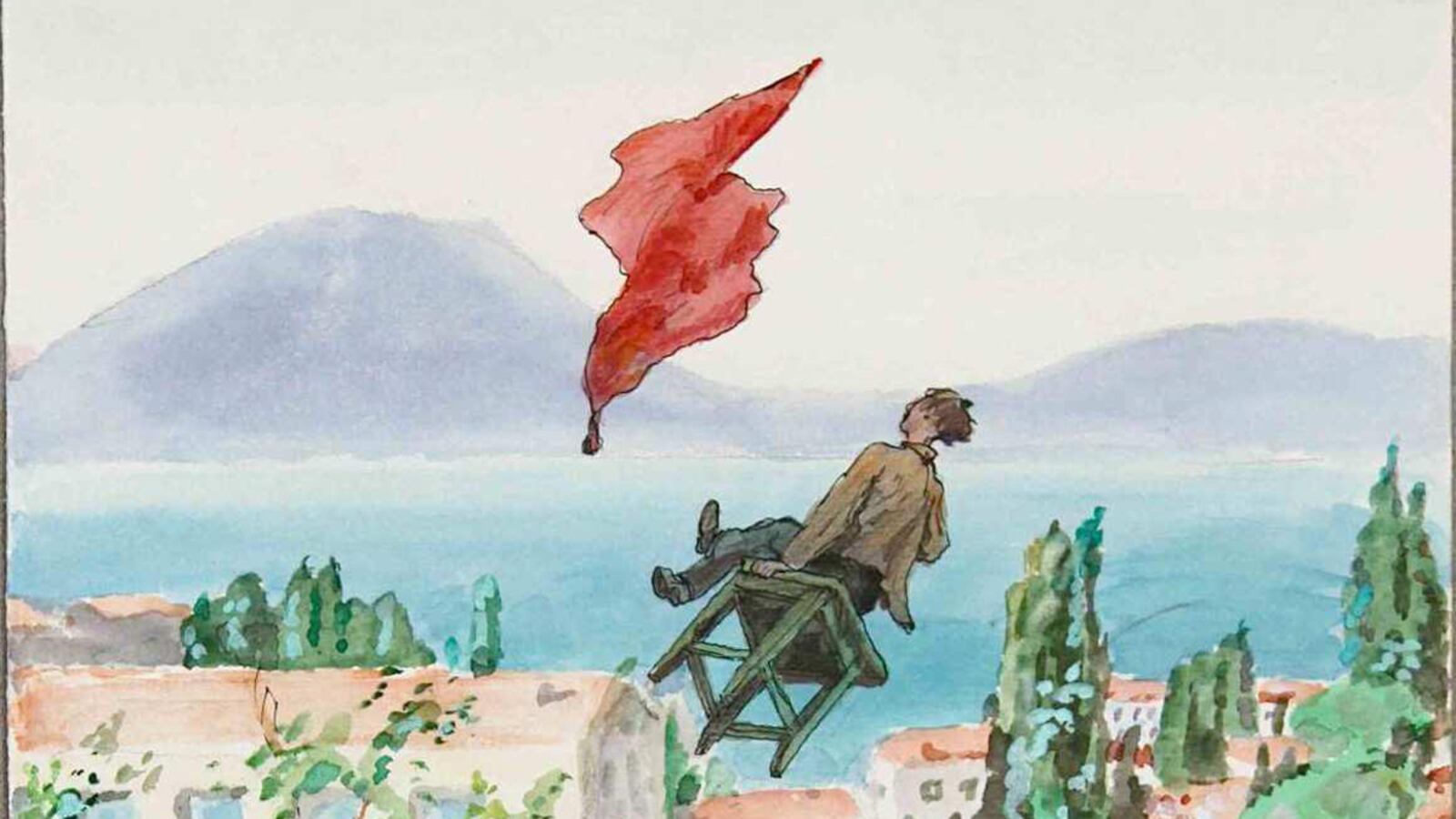

In the 1980s, the album’s cast came alive when Kabakov built the 10 Characters installation, a series of 10 rooms where the imaginary characters lived. The most famous of these was The Man Who Flew Into Space from His Apartment, which featured a hole in the ceiling, a giant slingshot, and a pair of shoes on the ground where the aforementioned “man” had stood before being catapulted out of sight.

The exhibition, which was mounted in 1988 at the Ronald Feldman Fine Arts gallery in New York, became a global sensation. The headline to John Russell’s review in The New York Times was “Ilya Kabakov Portrays Communal Soviet Life.” In the ‘60s, the Thaw introduced young Soviets to the libidinous Western world, but they still lived with their parents in cramped quarters shared with several other families that were called “communal apartments.” Critics thought the installation was an indictment of the lack of freedom in such Soviet environs. It helped that Kabakov was now famous and seemed to be in “exile,” having moved to America. (Emilia insists Kabakov never “emigrated” and doesn’t prefer the U.S. to Russia; it was simply easier to work in New York, where many of his exhibitions took place.)

“One of the biggest mistakes everybody does, unfortunately, is they limit the work together to the Soviet period. They put a label, which limits imagination, limits people’s knowledge, and even limits their curiosity. ‘Oh, because this artist does communal apartments, it’s about Soviet times. Soviet times are in the past, so we’re not interested.’ Which is absolutely not so. It’s not so from the very beginning. But unfortunately this is what happened,” Emilia said. “My closest friend tells me, ‘He does paintings? I didn’t know he does paintings. I thought he only does installations about communal apartments!’”

And now, 20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, such narrow readings might explain how Kabakov has fallen out of favor. He’s not a publicity hound, and still quietly sits in his studio, listening to music and producing art every day, rarely venturing out from his Long Island home. We don’t quite know how to deal with an artist like him, once we free him from the label of “political artist.”

Perhaps a more convincing theme that runs through Kabakov’s art is his propensity to disappear—fly away, as in the case of The Man Who Flew Into Space from His Apartment, or to vanish behind imagined personages, as in 10 Characters. “What people don’t understand is his mentality of escapism—escapism from reality, escapism from the system, escapism from everyday problems, escapism into art.” America, to Kabakov, is as lonely as any village in Siberia. Kabakov is the Beckett of the art world, creating silences and divorcing himself from the cackle.