It was hard to know who were worse at Saturday night’s Republican presidential debate, the candidates or the moderators. With American and European economic might in near collapse, and the world witnessing a once-a-millennium power shift from West to East, Scott Pelley of CBS News and Major Garrett of the National Journal waited until the debate’s closing minutes to ask about the global financial crisis—and when Jon Huntsman and Rick Perry tried to answer, Pelley cut each of them off.

The exaggeration of the threat America faces from jihadist terrorism and the minimization of the threat it faces from Asian economic power is one of the most disastrous legacies of Bush foreign policy. And listening to Pelley and Garrett—and their overwhelming focus on Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran (China was mentioned briefly; India not at all)—was to re-inhabit the world according to Dick Cheney, not the world in which America actually lives.

Then there were the candidates’ answers. In their debates on domestic policy, the Republican presidential contenders described America as a bankrupt nation, too poor to afford even the meager welfare state we have. It would be nice if someone introduced those candidates to the folks who debated last Saturday night.

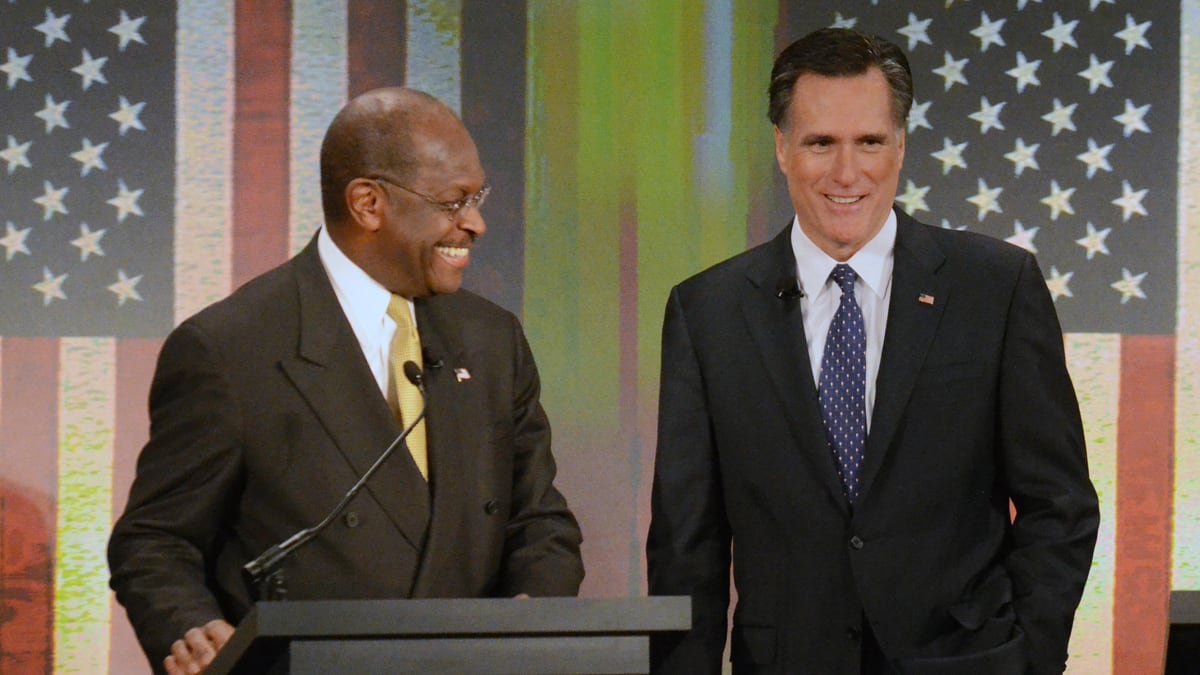

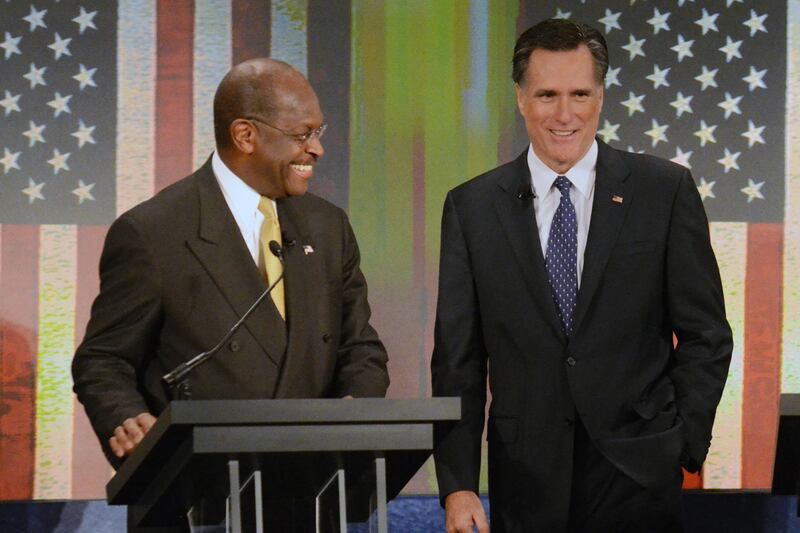

When Republicans discuss foreign policy, something miraculous happens: America’s economic constraints disappear. Oh, sure, Rick Perry and Newt Gingrich called for slashing foreign aid, the foreign-policy equivalent of Amtrak. But when it comes to defense spending, which costs nearly 20 times as much, and the overseas commitments that have sent that spending skyrocketing since Sept. 11, you would have thought America was flush with cash. Perry and Herman Cain criticized Obama’s timetable for withdrawing troops from Afghanistan; Michele Bachmann said Obama had sent too few to begin with; Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich ruled out negotiations with the Taliban; Romney and Rick Santorum declared themselves willing to bomb Iran.

How might war with Tehran—and the resulting disruption of the world’s oil supply—affect America’s economy? Who knows? The question never came up. What are the budgetary implications of revoking Obama’s timetable for Afghan troop withdrawal and refusing to negotiate a political settlement with the Taliban, thus closing off the only plausible avenue for ending the war? Why should the U.S. continue to spend $100 billion a year to fight a war in one of the poorest and weakest nations on earth when mammoth, prosperous nations increasingly threaten our preeminence? And how might it affect our chances of victory in Afghanistan if we go to war with Iran, its powerful neighbor to the east? Neither the moderators nor the candidates thought any of these questions important enough to even raise.

To listen to all the GOP presidential candidates—except Huntsman and Ron Paul—was to witness the power of inertia. When George W. Bush laid out his “war on terror” strategy after 9/11, he built it upon two premises. First, that “radical Islam” was as great a threat as Nazi Germany and the U.S.S.R. had been. Second, that by overthrowing Iraq and Afghanistan and pressuring authoritarian U.S. allies like Egypt and Saudi Arabia, the U.S. could bring liberty to the Middle East, thus sapping militant Islam’s support.

Saturday night, the Republican candidates barely even bothered to rehearse Bush’s arguments about the extent of the Islamist threat. None of the Republican candidates embraced Bush’s democracy-promotion agenda, and Cain and Gingrich denounced Obama for helping oust Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, thus repudiating Bush’s democratization policies in the process. And yet the top-tier candidates largely embraced the policies—in favor of an open-ended commitment in Afghanistan, in favor of war to prevent Iran from getting a nuclear weapon, and in favor of waterboarding and Guantánamo Bay—from which Bush’s “war on terror” derived. Why? Because it’s a dangerous world and America must always lead. It was the right-wing foreign-policy equivalent of Muzak.

The debate contained only three interesting features. First, Huntsman, whose substantive, thoughtful, honest answers to the few questions the moderators threw his way made him look like Yo-Yo Ma at an audition for America’s Got Talent. Second, Paul, who, regardless of whether you agree with all his policy views, at least tried to reconcile his foreign-policy perspective with his support for limited government at home. And third, the audience, which, for the most part, remained mum when candidates waxed hawkish on Afghanistan and Iran and clapped wildly when Paul said the U.S. should go not to war without congressional approval, when Huntsman said the U.S. should do its nation-building here at home, when Perry and Gingrich denounced foreign aid, when Gingrich threatened to reduce U.S. funding for the U.N., when Paul rejected U.S. intervention in Syria, and when Romney proposed tariffs against China.

Some of this simply may have been Paul’s powerful-lunged backers. But listening to the entire debate, it was hard to escape the sense that in the struggle to determine whether Barack Obama is destroying America by engaging too much in the world or too little, grassroots conservatives increasingly want less commitment. According to the Pew Research Center, in fact, the percentage of Republicans who think scaling back U.S. military commitments should be a top priority has risen from 29 percent in 2008 to 44 percent today. Even many of the Republican Party’s most loyal supporters, in other words, don’t find the candidates’ neoconservative belligerence convincing. Too bad they weren’t moderating the debate last Saturday night.