What if they had a trial of men charged with killing millions of people in a country and the wounded nation shrugged?

The world may be witnessing just such a phenomenon, as the Cambodian government and United Nations conduct the second multimillion-dollar trial in a three decade-long quest to bring to justice Khmer Rouge leaders accused of presiding over a 1970s wave of savagery that may rival Nazi Germany.

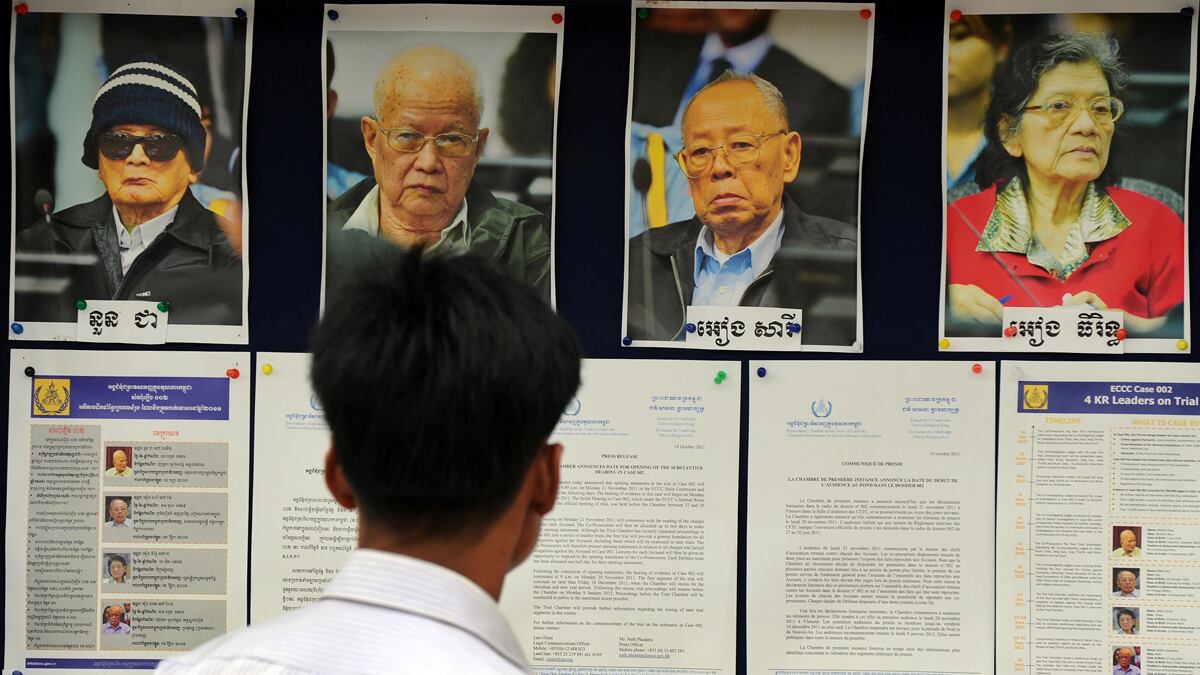

In the dock at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Court of Cambodia, less grandiloquently known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal, are Khieu Samphan, head of state during the Khmer Rouge rule from 1975 to 1979; Ieng Sary, the former foreign minister; and Nuon Chea, “Brother Number Two” behind strongman Pol Pot and the communist group’s chief ideologist. Ieng Sary’s wife, Ieng Thirith, who was minister for social affairs, has been ruled unfit to stand trial because she suffers from Alzheimer’s. The octogenarian defendants face charges including crimes against humanity, genocide, religious persecution, and torture. They are held responsible for the deaths of half a million to 2 million Cambodians, depending on who is counting.

The trial, which began Nov. 21 and resumes Dec. 5, is the second in Cambodia. The first ended in July 2010 with the conviction of Comrade Duch—Kaing Guek Eav—the commandant of Phnom Penh’s notorious Tuol Sleng prison, where an estimated 16,000 men, women, and children were tortured and executed, some by guards who smashed their skulls against trees. Duch admitted his crimes and received 35 years in prison but will likely serve 19 years, with allowance for time already served and other considerations.

The jailer’s “light” sentence provoked some outcry, but the proceedings, including the current trial with its bigger star defendants, appear to be a matter of ambivalence for the nation.

One reason is simply the passage of time. “Many Cambodians I talk to feel it would be better if they just let it go,” Jean-Michel Filippi, a linguistics professor at the Royal University of Phnom Penh, told The Daily Beast. “And to me, this is not genocide—that would imply a specific target. The Khmer Rouge seemed more like a steamroller, with the enemy constantly changing.”

A trial observer who has been in contact with one of the Khmer Rouge defendants was more emphatic: “Most of the Cambodian population doesn’t give a damn about this trial,” said the person, who would not be quoted by name on a sensitive subject. “So many [foreign] people are saying the trial will tell us what happened. It won’t; it’s not supposed to. It is merely supposed to establish guilt or innocence, not establish why those things happened.”

Some Cambodians, of course, do care about the trials. But many seem to regard them almost dispassionately, as a way to draw a line under an era.

“I think the trial is a good thing because they killed many people,” said Army Brig. Gen. Sek Seng. “The U.N. support for Cambodia is very good because we can find out the truth about the many millions of people who were killed. It’s a little too late, but it is a good thing for our nation, and for the Khmer Rouge too.”

Sek, who fought with the Vietnamese and Cambodian armies against the rump Khmer Rouge from 1985 until 2003, displayed no rage, even though he said Pol Pot arrested his elder brother—“We never saw him again”—and forced Sek to marry a woman he did not know in a ceremony that bound 22 couples in arranged marriages.

Leakhena Hun, a 22-year-old student, said she is one of few Khmers her age who are following the trial. She said five of her mother’s nine siblings were killed by the Khmer Rouge. “It’s very important for us as Cambodians to know who we are,” she said. “What they [the defendants] are trying to do is change history, but you can’t. What about the people who were killed?”

A prosperous Khmer restaurateur who spent six years in a refugee camp was more detached. “It’s good to have a good understanding of what happened,” said the entrepreneur, who requested anonymity because he feared jeopardizing his business. “To make the country go forward, get it clear and move onto other things.”

That is a feeling shared by Prime Minister Hun Sen. For years the prime minister, a wily politician who has managed to remain premier since 1985, resisted international pressure to hold the trials. To him, such show trials would eat up resources—not so much money, since the international community is paying most of the bills, but people and time—and would portray Cambodia in a bad light at a time when it is trying to project a can-do, modern image: “Every time CNN talks about Cambodia, they cut away to a pile of bones,” said a Western executive who is in contact with Hun Sen. “It’s a bad PR hit. There’s no way Cambodia comes out good in this thing.”

Moreover, the government long ago cut a deal with the aging Khmer leaders, including Pol Pot, who died in 1998, that granted them amnesty for giving up the rear-guard fight they had pursued from the jungles with their various armies. Indeed, Nuon Chea has publicly protested being hauled into court after receiving a royal pardon in 1998 for defecting from the Khmer Rouge. The prime minister eventually yielded on the trials, but he is adamant that there will be no more after this one, despite the blandishments of the international community.

His resistance has raised the ire of some critics, most of them foreign, who suspect he is afraid the spotlight may eventually be turned on his own past exploits as a low-ranking Khmer Rouge officer, and that any more scrutiny could destabilize the nation and jeopardize his rule, which some see as not only autocratic, but corrupt.

“The people who make these allegations do so because this government came to power with the help of the Vietnamese and they can’t forgive them for that,” said the trial observer. “Corruption is true, but it’s the same as the rest of Southeast Asia, especially Thailand.”

The signs of such corruption are visible all over Phnom Penh. Occupy Wall Street’s vaunted “99 percent” would find plenty of fodder in the capital, where a tiny number of elites live in ostentatious mansions and drive around in luxury vehicles. Generals, said to earn less than $100 a month from their official salaries, live in sprawling, lavish compounds. Interior Minister Sar Kheng is believed to be a hardliner who advocates a return to central planning and a one-party state, but he occupies a palatial estate on Norodom Boulevard—around the corner from Hun Sen’s own massive house on Sihanouk Boulevard.

“Corruption is not unique to this government,” said veteran Cambodia development worker Bill Herod. “It is ingrained in the culture. And corruption is a negative term. Cambodians don’t see it that way; it’s a parallel tax.”

It appears that for many Cambodians, getting ahead is the challenge at hand, not seeking catharsis from expensive show trials. “The international community tries to justify all the money they’re spending on these trials by saying it’s going to bring closure to the Cambodian people,” Herod said. “Nonsense. It is 30 years too late, and doesn’t have any bearing on the real experience of the survivors.”

Those survivors also marvel at the price of delayed justice. Duch’s trial is said to have cost between $150 million and $170 million. The current proceedings are expected to last up to two years, assuming the ailing defendants remain alive, and cost hundreds of millions of dollars more. The trials also have spawned their own cottage industry: many U.N. officials are billeted in luxurious walled residences and are driven around town in sleek black SUVs. Their lifestyle has not escaped the notice of locals, who wonder how it is any different from that of the Cambodian gentry who are maligned for their excesses.