Before we heard about Herman Cain’s 4 a.m. call to Ginger White, there was George Clooney’s in Ides of March, the fall film that featured a presidential candidate making a 2:30 a.m. call to the intern, who was in the sack with one of Clooney's top aides.

We all also remember Hillary’s 3 a.m. phone call ad in 2008, so we’re now in the midst of our third presidential election cycle, two of them real, dominated by early morning siren calls that test White House mettle.

But the mystery of Herman Cain is not whether Ginger White’s phone records will finally disconnect him from his 999 area code.

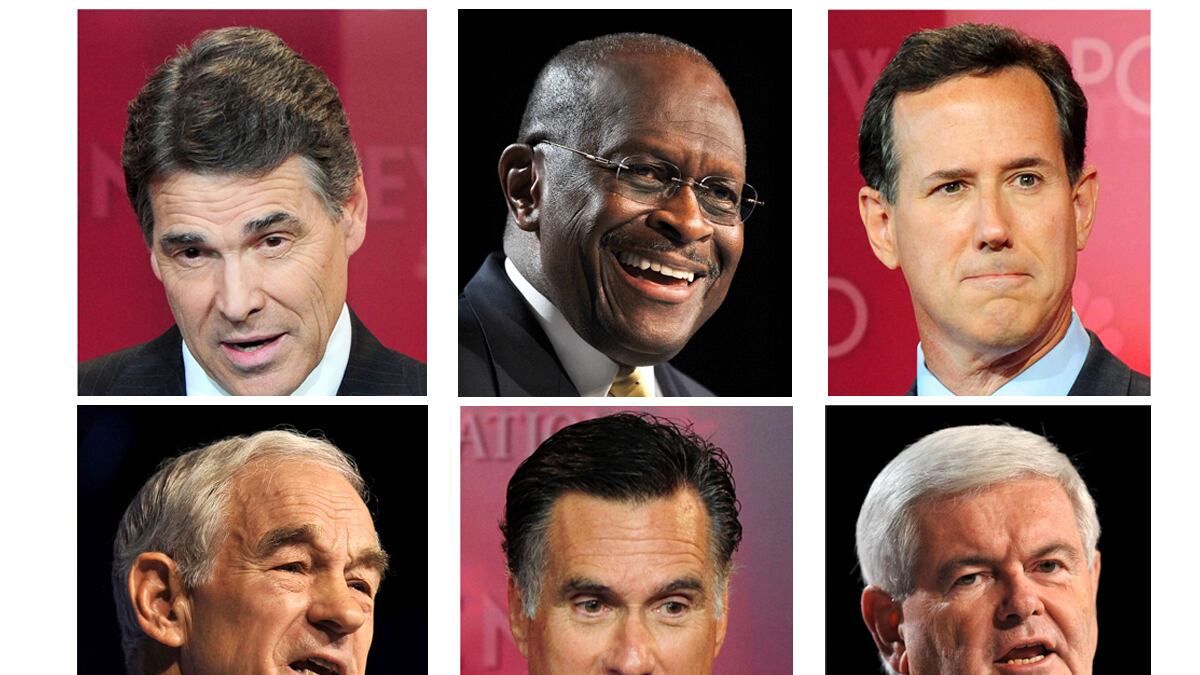

The reason we should all still care about this soon-to-be Invisible Man is the odd GOP phobia that caused his surge in the first place. How he became the biggest Mr. October since Reggie Jackson is a window into the psychosis gripping a party that, in a year, may be ruling all of Washington.

Essentially unemployed since he left the National Restaurant Association in 1999, confounded by Libya, a blogger who insisted there was no 2008 recession as late as that September, Cain nonetheless climbed to the top of the national, Iowa, and South Carolina polls and stayed there until the second week of November. The pizza man even delivered big wins in the Florida and Georgia straw polls. And when four women charged that he took his role as the head of the hospitality industry a bit too seriously, he brushed civil settlements aside as if they weren’t on his tab and still stalked the White House.

Ann Coulter, the poet of the party, explained it best, as usual.

In a careful and dispassionate treatise on race that Coulter performed on Sean Hannity’s show on November 1, just as the first sexual harassment charges emerged, Coulter found the words that would set the rise of Herman Cain to music. “Our blacks are so much better than their blacks,” she hummed, adding that Obama was only “half-black,” and that half could also be discounted because he is “the son of a Kenyan.” Obama, Coulter lectured, “is not the son, the grandson, of American blacks who went through the American experience. That is Herman Cain.” Cain had, in Coulter’s view “many wonderful qualities” but the same Democrats who “used to do lynching with ropes” were now doing it with “word processors” and were telling “vicious” lies to bring down a conservative black, just like they tried to do with Clarence Thomas.

The Cain phenomenon was a spectacular explosion of Obama obsession, a frenzied attempt by a party of white male elites to demonstrate that it has blacks that aren’t merely dancing extras at a Republican National Convention, à la 2004. Trashtalking Herman with his ballyhooed claim that Democrats had “brainwashed” blacks could, with one long smile, put a fake face on a party that included 36 black delegates (1.5 percent) at its 2008 convention, the lowest representation since the year Martin Luther King Jr. was killed.

The party that called affirmative action “racism disguised as a social virtue” in its 2008 platform flirted with it for all the weeks that Herman Cain flourished. When Cain ran for the U.S. Senate in 2004, before the Obama triumph, he was trounced in a GOP primary in Georgia. But a large enough slice of the party in the Obama era wanted so desperately to lay claim to its own black that they embraced the ultimate product of affirmative action, a black businessman whose every step up the career ladder got a black boost, and turned his meteoric candidacy into an example of racial preference itself, conscious or subconscious. There is no way a white man with Cain’s resume would ever have led that field of governors and members of congress, current and former.

Consistent with the party he was charming, Cain has long made his opposition to affirmative action clear, contending during his 2004 senate race that University of Michigan admission bonus points for minorities was “unconstitutional” and opposing what he called any “special government preference” for minorities. “I don’t have a lot of patience for people who want to blame racism for the fact that some people don’t make it in America,” Cain told Hannity, consistent with his celebrated instruction to the Occupy protesters, telling them to “blame yourself” if they don’t have a job. His just-published book is a repetitious rejection of the “black victim mindset” and a salute to those who are up-by-their-bootstraps “CEOs of self.” Asked during a July appearance on a Nashville radio show about the possible effect of race on his career, Cain declared: “I didn’t benefit from affirmative action at any point in my career, because of my performance.”

The startling nearly two-month success of his presidential candidacy belies that. As does the life story that the Daily Beast has taken a long look at, a saga whose significance will not disappear with his candidacy. Herman Cain is the embodiment of the contradictions that haunt a party that’s seceded from Lincoln’s land, and is in search of pretense, even if it requires preference.

The Cain story, as he and the media recount it, has him working his way up at Pillsbury Company and its subsidiary Burger King, flipping hamburgers on the way, then rescuing the floundering pizza franchise Godfathers, before taking the helm of the National Restaurant Association. Despite the presidential campaign’s spotlight, it’s passed unnoticed that Cain’s climb took place within a company plagued for 16 years by a succession of legal discrimination cases and forced to negotiate with Jesse Jackson’s Operation PUSH to reverse a proven pattern of discrimination. Every advance in Cain’s career tracks this timeline of legal tensions, which featured two class-action settlements involving minority Pillsbury employees and another lawsuit centered around Burger King minority franchisees.

Three years prior to Cain’s 1977 arrival at the Minneapolis-based Pillsbury Company, Marceline Donaldson, a former black employee, sued the company on behalf of all female and minority employees. Donaldson’s case, filed by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, was dismissed in 1976. But in April of the following year, the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the lower court’s decision, finding that Donaldson had “made a showing that a significant number of other members of the class have been similarly victimized by the same patterns.” The appeals court warned that Donaldson had “laid a proper foundation to pursue a full-scale inquiry into Pillsbury’s alleged unlawful practices.” The complaint revealed that less than 1 percent of Pillsbury’s officers and managers were black.

Cain was working at Coca Cola in Atlanta in 1977 in a position he describes in his own memoir as a low-level managerial position without much promise of promotion. His former Coke supervisor, who’d moved on to Pillsbury three years earlier, recruited him to come to Minnesota as Pillsbury’s manager of Corporate Business Analysis. With the Donaldson suit hanging over the company during protracted appeals and legal wrangling until 1983, Cain soon enjoyed a series of rapid promotions. In 1980, he replaced his boss, Dr. John Haaland, as vice president of systems and services, the first big title of his life. A Ph.D. in biophysics who later founded Mindsong, Haaland was so accomplished he’d played a key role at Honeywell designing systems for the Apollo space missions. When Haaland was promoted to run Project Galaxy for Pillsbury, plotting its corporate future for the next 20 years, 34-year-old Cain, who earned a master’s in computer science while in the Navy at Purdue, was elevated to his post.

Then, in early 1982, with the Donaldson case still proceeding and Jesse Jackson threatening a black boycott of Burger King because minorities owned a meager 2 percent of the company’s 3000 franchises, Cain was offered a “fast-track” ascension to one of the restaurant chain’s ten regional general manager’s positions that required him to do nine months of training on the ground. Late that year, he became the vice president for the Philadelphia area overseeing 400 Burger Kings.

Donaldson, a Republican businesswoman in Massachusetts today, told the Daily Beast that Cain “calls himself a self-made man,” but “wouldn’t have gotten to first base without those lawsuits.” Cain was hired, says Donaldson, “when Pillsbury realized they had to make some changes. He could get what he wanted but he didn’t get it going down the middle of the street; he’d get it bobbing and weaving.” Donaldson, who’s so feisty she once sued Louis Farakkhan because the Nation of Islam wouldn’t let her attend a public meeting, posted two blogs last month, urging Cain to acknowledge the role that the civil rights movement played in his success, and then condemning him for being “unable to see, respect, or thank those on whose shoulders he stands.”

“You got your job through affirmative action and the work of civil rights groups who intervened and opened a path for you,” Donaldson wrote. In June 1983, Pillsbury reached a $350,000 settlement with Donaldson, part of which would fund an “education, scholarship and internship program for blacks.”

A few months before that and shortly after Cain became Burger King’s first black regional manager, Jesse Jackson announced a $500 million affirmative action agreement with the hamburger group. The agreement called for increased minority participation in “all areas and levels” and laid out specific targets, including raising black employment to 21 percent, black ownership of franchises to 15 percent, and hiring a black advertising agency that would receive 15 percent of Burger King’s promotional work. Asked it the PUSH pressures had anything to do with Cain’s promotion at Burger King, Frank Watkins, Jackson’s top aide, says, “It would make sense in light of the agreement.”

Byron Lewis, owner of the black advertising agency hired by Burger King after the Jackson agreement, recalls meeting Cain and finding him “affable.” But he is distressed about him today, noting, “It’s difficult for me to understand why people would not be candid and say they owe it to affirmative action. Jesse Jackson opened the door for executives in that company. It’s embarrassing to me when people have trouble saying how they got there. Almost every major executive of color that I know of would find it hard to dismiss the real influence of affirmative action. There were no black executives at that time.

Another black business associate of Cain’s at the time was Brady Keys, a Burger King franchise owner from Detroit highlighted alongside Cain in a 1989 Nation’s Restaurant News editorial on barriers facing black executives in the restaurant industry (Cain in this same article, is described as the “Jackie Robinson” of the food service chain industry). “Herman benefited from the same affirmative action I benefited from,” Keys said. “They didn’t tell me that and they didn’t tell him that. It just so happens that I acknowledge it.”

Ron Edwards, chair of the Minnesota Urban League and the Minnesota Civil Rights Commission at the time, got to know Cain fairly well and told the Daily Beast, “In those early years, he was taking advantage of the lawsuits and the significant pressures being exerted by those in the forefront of civil rights in this city. He played affirmative action to the hilt and took full advantage of it. All this rhetoric about pulling himself up by the bootstraps, a single crusader, predicated on his own greatness, it’s hogwash. This is not the Herman Cain some of us came to know here.” Edwards said that Cain “played it safe” and never got involved in the Donaldson suit and other efforts to put pressure on Pillsbury, but then asked him if he could get on a position on the Urban League board. “I said that wasn’t possible,” Edwards recalls. “He couldn’t get out of the nominating committee.”

Cain got high performance marks over the four years he ran the Philadelphia area for Burger King. But his next promotion was also connected with a second Pillsbury agreement with Jackson’s PUSH, as well as the beginnings of a second class-action lawsuit by black employees. Pillsbury acquired troubled Godfather’s Pizza in 1985 as part of a broader deal with Diversifoods, a food conglomerate that also owned 300 Burger King franchises. In March 1986, Cain was summoned by Pillsbury restaurant division brass to Miami and asked to take over the running of the newly acquired company. He’d never worked in the pizza business and never run a company, saying later he was “only remotely familiar with Godfather’s” at all. That December, Jackson signed a five-year extension of his agreement, giving the company until 1990 to reach the 21 percent hiring goal.

Discrimination complaints with equal employment and human rights agencies were also being filed by black employees in the same period, eventually culminating in another class action lawsuit that would not actually appear on a federal docket until 1989, shortly after Cain’s departure from the company. However, settled a year later for $3.6 million, the 274 ex and current black employees covered by the case worked at the company between 1984 and 1989, a period when Cain got his Burger King and Godfather promotions. Paul Sprenger, the Washington, D.C. employment discrimination attorney who brought the case, says he started working on it in 1987, and it was rooted in individual complaints filed as far back as 1985.

“I do remember talking about Herman Cain,” says Sprenger. “My clients had talked to him and he was going in his own direction. I think he was considering becoming involved with my clients and in the end he didn’t. I think he benefited by playing both sides.” Pillsbury, Sprenger recalls, “didn’t want Cain” to join his clients. “Cain is not a dumb guy. He was using that, I think, to get the benefits he has gotten without having to sue anybody.” Sprenger says his clients met with Cain “on several occasions,” and “I have this sense he was negotiating on his own.”

He sure did well. Not only did Cain become Godfather’s president, Pillsbury decided to sell him the company on the cheap. The extent of Godfather’s rebound between the time he took over in April 1986 and Pillsbury decision to sell it to him in January 1988 is a matter of dispute, but it’s generally agreed that he helped slow the slide into red ink. Of course, if it was such a turn-around, why did Pillsbury sell a company generating $242 million in sales for $40 million? Why did it never put Godfather’s, which Diversifoods had purchased a mere two years earlier for over $300 million, on the market, offering it instead exclusively to Cain and his deputy on firesale terms negotiated in two quick weeks? Why did Pillsbury then give Cain nine months to arrange financing, keeping the company on ice until late September, when Cain finally got Citigroup to pony up the puny purchase price?

We called half a dozen ex-Pillsbury executives about these and other Cain questions and no one will answer them. Pillsbury was acquired by a British conglomerate in 1989 and they moved quickly to settle the Sprenger suit (“they weren’t going to waste anytime litigating,” says the lawyer, “so they did pay our clients well”). Since then, it’s been purchased by General Mills and the company’s press office won’t answer any questions about anything that preceded its ownership. But the juxtaposition of the efforts by Sprenger’s clients to draw Cain into their legal battle with the timing of Pillsbury’s otherwise inexplicable deal with Cain suggests that race, once again, might have been a factor.

Indeed, a month after the Godfather’s-to-Cain sale was finalized, another, long-brewing discrimination lawsuit was filed against Burger King. Twelve black franchise holders were behind the $500 million class action suit, which claimed the company had a history of placing minority-owned restaurants in poor, urban locations, and blocking attempts by minority owners to obtain loans. The lead plaintiff’s attorney, Charles Ware, told us that the allegations dated back to 1984, when Cain was still working for the company. Ware says it was eventually dismissed for technical reasons, though the company did settle individually with some franchisees.

“There were truly egregious allegations,” Ware said. “Burger King wasn’t any more than a plantation, and for Herman Cain to have risen during that period, through the ranks, would not have been just on merit.”

This is the history of a man who until recently was the frontrunner for the Republican presidential nomination and became a conservative cause, championed on the right as the very thing he has spent a lifetime denouncing, a black victim. He’s hardly the only one to turn this presidential nominating process into carnival, with people still flocking to his show, but the lust for him on Fox and in other GOP quarters is an embarrassment they should be held accountable for, even after he vanishes from the campaign.

Research assistance was provided by Emily Atkin, Matthew DeLuca, Kelly Knaub, and Fausto Giovanny Pinto.