Back in February, as I watched Herman Cain work a convention pressroom of conservative bloggers, half of whom didn’t bother to look up from their laptops, I could see that the man had an innate charisma—and needed the media as a megaphone.

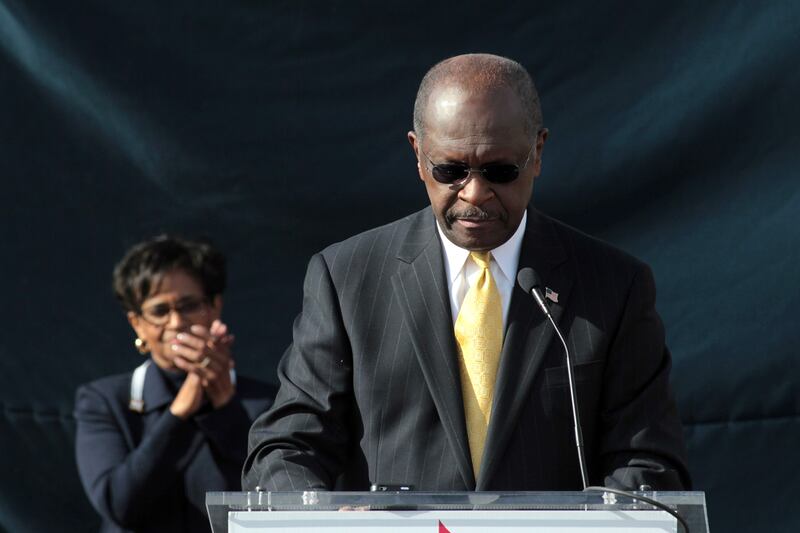

On Saturday, Cain had cable anchors filling time for hours until he finally walked out at his new headquarters in Atlanta and announced he was suspending his presidential campaign—with several hard shots at the media establishment.

“The pundits would like for me to shut up, drop out, and go away,” he declared. That’s not true—the man was hugely entertaining for those of us in the press corps, even as we struggled to figure out his appeal.

Give him this—he made himself a household name. That was a mixed blessing, of course, since it was accusations of sexual harassment by three women, of groping by a fourth, and of a 13-year affair by Ginger White this week that boosted his name recognition into the stratosphere. Cain never came up with clear and convincing denials, especially in the case of White, since he admitted paying her money without telling his wife.

But for weeks he seemed to defy political gravity, despite the disturbing allegations. He would often seem not to know what he was talking about, delaying for an agonizing 53 seconds before attempting to answer a question about Libya. He had trouble defending his 9-9-9 tax plan. Journalists had a tendency to regard him as a fringe candidate, and yet there he was, leading the GOP polls.

And give him this: no African-American has ever risen so high in a nomination contest within the largely white Republican Party. People liked his story—rising to run the Godfather’s Pizza chain, beating cancer, claiming the outsider’s mantle—and they liked him.

There were glib explanations: he was simply the repository of anti–Mitt Romney sentiment, like Michele Bachmann and Rick Perry before him and Newt Gingrich after him. Maybe so. Cain was never going to win the nomination; we all knew that. But he did have an appeal to conservative voters that journalists could never quite figure out.

The irony was that Cain increasingly took to bashing the media as the sexual allegations mounted, even though it was the endless television interviews and cable news debates that formed the basis of his campaign. He was on the cover of Newsweek just a few weeks ago. His was a virtual candidacy, with little money or organization, but for a time, that was all he needed.

Cain was less attractive when he spoke darkly of “character assassination” and media-enabled plots to undermine him. He created his own problems, his former employer having settled two harassment complaints and he himself helping to support the woman who says she was his mistress. There was no concerted effort to undermine him; he undermined himself.

In the end, Cain failed because of a disorganized campaign, his inability to master the issues, his stumbling responses to the women’s charges, and perhaps a naiveté that his personal baggage could remain safely stored in the closet. He couldn’t even make it to Iowa. But he sure livened up the campaign.