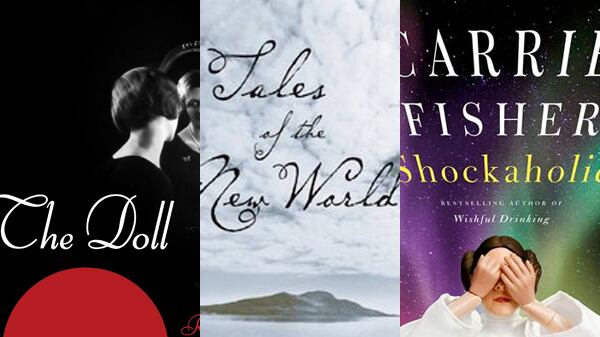

The Doll: The Lost Short Stories

Du Maurier’s pre-'Rebecca' stories provide a fascinating glimpse of a gifted young writer finding her niche.

The worst that can be said of the 13 early stories in The Doll (collected here for the first time) is that they sometimes collapse under the weight of their own willed pessimism. At this point, while she was still in her 20s, Du Maurier was overly fond of creating optimists who you know right away are headed for a fall. She had not learned the lesson that she would put to such excellent use in Rebecca—that to make her character’s paranoia and sense of inadequacy palpable, she would need to get inside the character, not merely stand on the outside and mock. But here’s the real lesson this book teaches: she never had much to learn. These stories are the work of, if not a genius, then certainly a pro. Some, like “Piccadilly” and “Week-End,” are merely accomplished character sketches. But others, such as “East Wind,” “The Doll,” and “The Happy Valley,” blur the line between reality and dreamscape, the territory where she would always do her best work (The Birds, Don’t Look Now). It’s a strange world, resolutely mundane and ordinary, but strange and creepy, too, a world where azaleas and hydrangeas cast their “tentacles” at the heroine, and already unmistakably Du Maurier’s signature preserve.

Mamma Mia! Berlusconi’s Italy Explained for Posterity & Friends Abroad

A socio-political guide to understanding Italy’s tolerance for its 'Emperor of Embarrassment.'

Though they dare not admit it, many Italians are likely mourning Silvio Berlusconi’s recent resignation as prime minister. Beppe Severgnini’s Mamma Mia! explains his popularity at home to “friends abroad” still scratching their heads as to why the beleaguered premier lasted as long as he did. Mr. B seduces Italians, Severgnini says, by living their romanticized dolce vita: “His passion is boundless … It fuels daydreams and provides justification for inexcusable yearnings.” Lest we forget that the Italian psyche is historically rooted in decadence (think Roman bacchanals and Fellini films), Severgnini outlines 10 reasons why the Italians tolerate, even cheer Berlusconi’s lavish lifestyle, along with his machismo manner, flagrant philandering, and power politics. From the Divine Factor (he praises Catholicism despite ignoring its tenets) to the Zelig Factor (like the chameleon-esque character in Woody Allen’s film, Berlusconi is at once “an ordinary guy with Zapatero and a man of the world with Sarkozy”), Severgnini decodes the former premier’s enduring appeal. Shedding light on the country’s shaky political and economic climates, Mamma Mia! is a colorful guide to understanding Italy today.

Pulphead

A collective work of literary bravura from one of the best American essayists writing today.

Though Pulphead centers on American culture, its contents are all over the map—Hurricane Katrina! The Real World! Nineteenth-Century Botanists! But Sullivan’s singular voice, reportorial expertise, and exuberant curiosity tie the disparate topics together, making his collective essays read almost like a memoir. Some are personal, like Sullivan’s account of being a live-in apprentice to Southern literary crusader Andrew Lytle, or his vivid description of his brother’s near-death experience after being electrocuted. His personal essays are deftly infused with subtle existentialist musings. Others are more obviously esoteric: a piece about Constantine Rafinesque, a 19th-century naturalist who nearly beat Darwin to his evolution theory; an analysis of prehistoric cave art in the American South (an oft-overlooked “incubator of civilization”). The rest of his “pulp” nonfiction covers Bunny Wailer, Axl Rose, Michael Jackson—not groundbreaking territory, but Sullivan makes it fresh. Regardless of the subject matter, Sullivan maintains a brilliant balance between gentle humor and profound insight throughout this standout collection.

A Convenient Hatred: The History of Antisemitism

An unparalleled education on discrimination against Jews.

A Convenient Hatred tells the long history of anti-Semitism, from ancient Egypt to the 21st-century Vatican. Published by an educational group, Facing History and Ourselves, dedicated to fighting racism, hatred, and prejudice around the world, the first chapter of the book takes us back more than 2,500 years to the anti-Semitic stereotypes that arose in Egypt under Persian and then Roman rule. Goldstein weaves powerful stories throughout history that still, alas, resonate today, illuminating how our wont of distinguishing “us” and “them” can breed hatred. In the book’s foreword, Reuters editor-at-large and Daily Beast contributor Harold Evans defines anti-Semitism as a “mental condition,” “a very peculiar pathology that recognizes no national borders,” yet still spans the globe. He points out how the fear of difference— “of faith … of custom … of culture”— readily manifests through discrimination: “the poison proliferates in receptive minds, where it congeals into an unyielding conviction.” A Convenient Hatred reminds us to beware the world’s purveyors of ill will.

Shockaholic

In her second memoir, Fisher peppers absurd tales with unexpected poignancy.

In her latest self-mocking monologue, Fisher revisits her bipolarized Hollywood misadventures while undergoing memory-zapping electroshock therapy. Fans familiar with Fisher’s various addictions and mood disorders plumbed in her 2008 memoir, Wishful Drinking, will appreciate fresh offerings from an “eager-to-please fucktard blathering on about her drug addiction and mental illness and her poor sad life.” Shock treatments have nearly shaken her manic-depression, but they’ve also chipped away at her short-term memory. Fearing permanent amnesia, Fisher jots down lurid details of her neuroses and celebrity exploits with characteristic acerbic humor. “Wishful Shrinking” chronicles how she became a Jenny Craig “poster girl for enormousness.” (Sure, the lucrative deal made her a “whore of giant proportions,” but if it were just about the money, she would have sold “Star Wars–scented laxatives.”) Fisher brilliantly skewers Ted Kennedy in “The Senator,” recounting his casually misogynist dinner-party banter. Shockaholic ends with a pitch-perfect tribute to her father: when he told his daughter months before dying, “I wish I had your life,” Fisher reassured him, “You did, Daddy. That’s why you’re in bed.”