The Greatest Punishment of All

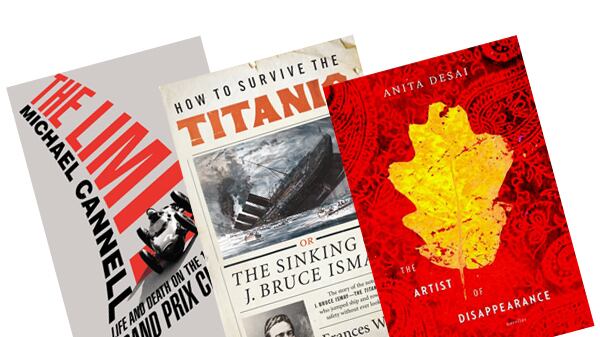

Frances Wilson is the thinking man or woman’s biographer. In her fourth book, she takes J. Bruce Ismay—managing director of the White Star shipping line and survivor of the sinking of the Titanic (one of his own boats)—and, alongside a meticulously researched and eloquently written account of one of the 20th century’s most iconic disasters, explores a man “mired in the moment of his jump.” Ismay was ever after resigned to a “survival with no future,” a “posthumous existence” that, Wilson argues, mimics the fate of the central protagonist in Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim.

Of the 2,340 passengers and crew on board the boat, only 705 (325 of which were men) survived the disaster, despite there being lifeboat spaces enough for 1,100. Wilson jumps right in at the deep end with a multitude of conflicting supposed eyewitness, accounts of Ismay’s actions that night, the “most common accusation was that Ismay had not behaved as a gentleman.” Gentlemen put on their dinner jackets and stood on the deck bravely going down with the ship; Ismay on the other hand cowardly boarded a lifeboat still dressed in his pajamas.

At the U.S. Senate inquiry held into the sinking immediately afterward in New York, and again at the British inquiry held at a later date back in London, Ismay was unable to satisfactorily account for his decision to jump ship. Stuck as he was in a sort of no-man’s land between customer and crew, he had “nothing to conceal and everything to conceal, he was both a passenger and not a passenger,” and on repeated questioning he contradicted his own account as much as those of others. Ending up listing what he didn’t see (“I saw no passengers in sight when I entered the lifeboat”; “After I left the bridge I did not see the Captain”; “I saw no women and children waiting when I entered the lifeboat”) rather than what he did, these “non-answers,” Wilson argues, “resemble nothing so much as the trial of the Knave of Hearts in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where the King confuses what is important with what is unimportant.” Wilson continually uses examples from literature such as this one here to illuminate the real life events that played out, but it is to Lord Jim and Conrad himself to whom she is most indebted. Conrad’s story, she explains, “can be told in a single sentence: Jim jumps from a sinking ship and then faces a life without honour”: Jim is Ismay, Ismay is Jim.

Some might note a somewhat slower pace in the second half of the book, after all, once Ismay has abandoned ship his life effectively draws to a halt, but this is the point where Wilson comes into her own, for this is exactly the problem with which her study contends. “The second half of lives, as well as novels,” she writes, “can also be of limited interest.” For while “Conrad used the half of his life spent on land to translate into romance the monotony of the half he spent at sea … what is curious about Ismay’s life is that having jumped from the Titanic into Conrad’s world … his story was quickly given a Conradian second half.”

But Wilson doesn’t let her analysis of the relationship between the two end there. “Using Jim’s story to reflect on Ismay’s,” she argues, is also “to see how characters who live in fiction have more appeal than those who do not.” Ismay may be “less sympathetic” than Jim, but equally “an evening spent with Hamlet in a hotel bar” would be “less engaging than an evening spent watching him perform his indecision on stage,” and Emma Bovary would quickly become a “bore” if she was always moaning down the telephone to us. “As with a mirror,” Wilson explains, “the distance afforded by art adds depth of vision; art increases our capacity for sympathy.” And seen through Conrad’s “hooded eyes,” Wilson ultimately proves that Ismay has indeed “something of the tragic hero” about him. Sometimes the greatest punishment of all is being “forced to live on.”

—Lucy Scholes

The Speed Artist

In 1951 a young racecar driver named Phil Hill inherited some money after his parents died within a few weeks of one another. Hoping to bolster his professional fortunes, Hill went shopping for a Ferrari. He found one with a pedigree—just a few months earlier, Frenchman Jean Larivière had driven the Italian-made car in the storied 24 Hours of Le Mans. But as Michael Cannell writes in The Limit: Life and Death on the 1961 Grand Prix Circuit, the vehicle had a harrowing flaw: “a hole in the floor drilled to drain Larivière’s blood.”

Though Larivière was decapitated when he crashed the car on one of Le Mans’ demanding corners, Hill wasn’t put off. After all, fatal accidents were an all-too-common part of midcentury auto racing, and drivers learned that the ability to compartmentalize their fears and superstitions was a crucial part of the job. For Hill, this was never easy. He was a bundle of nerves throughout his career, but as Cannell recounts in this winning book, Hill would prove to be a groundbreaking figure in the history of international racing—even as his accomplishments were met with a collective shrug of the shoulders in his native country.

Ostensibly about a single Grand Prix season, The Limit is also a biography of a man whose ambition and fascination with technology embodied America’s post–World War II ethos. A child of the 1930s, Hill grew up wealthy in an era when millions of Americans were suffering the aftereffects of the Great Depression. The Hills neighbors included Shirley Temple, and Phil attended school with the grandson of William Randolph Hearst. Hill, however, found speed far more thrilling than status. As teens, he and fellow car lover George Hearst Jr. “drove the private roads of the Hearst estate in Santa Monica Canyon,” Cannell writes, “and they staged races on a quarter-mile horse track on the property, skidding their way around the dirt oval.”

At the end of the 1940s, after dropping out of college and learning that his sinus troubles would preclude military service, Hill went to work for a team that raced small speedsters, so-called midget cars. He was a fish out of water—as Cannell notes, this brand of competition was “taken up by tough young men from blue-collar neighborhoods”—but Hill seems to have made an easy transition. Hired as a mechanic, he would soon find himself behind the wheel, yet “he found oval racing a deadening merry-go-round.” Hill longed for a shot on the road courses that were so popular in Europe.

That Ferrari, with its frightening history, gave Hill reason to believe he might get there. He acquired the car through a deal brokered by Luigi Chinetti, an Italian racing champion who served as a link between Enzo Ferrari’s Modena-based company and up-and-coming American drivers. Chinetti began to offer career advice to the young American, and by 1953 Hill was an alternate member of a team that took part in that year’s 24 Hours of Le Mans. But a series of accidents would soon kill several of his fellow drivers, and though Hill “wanted to keep racing,” Cannell writes, “his psyche rebelled.” He considered calling it a career.

Hill found off-screen work in the movies—he taught Kirk Douglas how to drive Italian sports cars for the Henry Hathaway’s The Racers—but he felt the need to compete again. In 1955 he returned to Le Mans as a competitor, and this time he witnessed perhaps the worst moment in the history of his sport when an accident involving French driver Pierre Levegh’s Mercedes killed more than 80 people, most of them spectators: “The last thing Hill saw before taking his first laps was a gendarme with his leg neatly severed.”

Hill steeled his nerves, and he would enjoy some success in the late ’50s. But his strong showing at races in Italy, Morocco, and Germany were just a prelude to the 1961 season. Though the book’s subtitle suggests otherwise, less than a quarter of The Limit focuses on ’61. But this is a canny move on Cannell’s part. He tells his story slowly, takes time to add context and sketch portraits of the circuit’s key figures, and then, in the book’s final two chapters, he spins a tense race-by-race narrative.

Hill’s chief rival would be fellow Ferrari driver Wolfgang von Trips, a German count who developed a reputation as a driver who was always a threat to win—as long as he didn’t wreck his car. In the years leading up to 1961, von Trips crashed at least eight times, and during a round of handwringing about racing’s safety in the German press, his mother was quoted as saying she wanted Wolfgang “to put a stop to his gruesome sport.”

Cannell does a thorough job of portraying the contrasts between the two drivers—von Trips was a playboy; Hill a relative recluse—and he conveys the epic nature of the intercontinental contest without ever overselling the facts. Von Trips and Hill battled it out on courses in Monaco, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Britain, Germany, and Italy. Racing diehards, of course, will know the outcome. But the rest of us will come to this story blissfully unfamiliar with the thrills and sorrow contained in the book’s last 70 pages.

—Kevin Canfield

A Fading India

Regret, disappointment, and despair color the lives of the characters of The Artist of Disappearance, author Anita Desai’s latest book, which is made up of three novellas. In these stories, Desai casts her gaze backward to conjure a fading era. Though “details of time and place are left deliberately vague” (as Desai notes in a recent interview), the India of this volume is clearly not the “new India” of booming economic growth and rapidly shifting fortunes; it is an older India of fading dynasties and postcolonial habits.

Desai has been nominated for the Booker prize three times in her long career, and her authority as a seasoned storyteller is on full display in her latest work. Each novella in this book unfolds slowly, ambling through expository digressions with confidence. Fittingly, the most intriguing tale in this volume, titled “Translator Translated,” examines a literary life. The story follows the fortunes of Prema Joshi, a discontented, spinster English literature instructor at a girls’ college. Prema’s career has been at a standstill ever since she stubbornly elected to focus on an obscure provincial language writer—rather than a more conventional figure from the canon—for her undergraduate thesis. When her work gets no special recognition, she is relegated to a middling teaching position, and left with “a small smouldering ember deep inside her soul (so she designated its location, no other would do),” Desai writes, “where it released an odor of heated rubber, threatening to destroy whatever pleasure or satisfaction she might court.”

When she gets a late-life opportunity to embark on a second career as a translator, Prema’s elation at being at last able to put her talents fully to use quickly balloons unchecked.

Translating the rural writer she passionately studied so many years before fills her with uncontrollable pride. She takes liberties in her translations, is found out, and—just as quickly as they began—her adventures in translation come to an end. Like Desai herself, Prema is caught between languages and cultures; unlike Desai, Prema is unable to put a voice to her own experiences. It’s a lesson in the seduction of a life in letters and capriciousness of fate, but also in the extent to which we each have the power to write (and unwrite) our own success.

Desai, at her best, offers enchanting, subtle, and deeply observed portraits of layered characters trapped between worlds. Unfortunately, the title story, “The Artist of Disappearance” misses the mark. Ravi, the adoptee turned orphan turned recluse “artist” of this story never exists fully enough on the page for his “disappearance” to be missed, and though the secondary figures of this title novella briefly sparkle with life, none has a lasting presence in the story.

Where the book hits its stride is in “Museum of Final Journeys,” a story that follows a young civil servant in training to his first rural outpost, where he is met with mosquitoes, drudgery, and isolation. It’s a far cry from the adventure that drew him into the service, and he confesses that, filled with loneliness and self-doubt on the job, he nearly “shed a tear or two in my flat grey pillow” in his first night on the job: “I came close to it but morning rescued me.”

Just as he begins to grow accustomed to the suffocating routine of work in his remote station, the young government officer is approached by a strange servant of a crumbling estate, who begs for his help: he can no longer adequately preserve the many beautiful artifacts accumulated by the estate’s former owners. His curiosity piqued, the officer agrees to make a visit to the “museum,” but after touring the labyrinthine property his mood changes sharply:

As for me, all desire I had ever felt for adventure had been drained away by seeing these traces that he had left of his, this gloomy storehouse of abandoned, disused, decaying objects. Their sad obsolescence cast a spell on me and I wanted only to break free and flee.

The final artifact is a live elephant whose capacious appetite is slowly eating into the estate.

Years later, when remembering back on the strange servant of that strange house, the no-longer-young civil servant fleetingly wonders if he did enough: “But it is not for us to do everything for everyone,” he reasons. Why, when finally presented with the glimmer of opportunity to take on a project more dynamic than his usual, dreary work, did he flinch? There may be only one “Artist of Disappearance” in this volume, but Desai presents the reader with many experts in lost identities, squandered promise, and missed opportunities in this melancholy—but memorable—new work.

—Mythili Rao