When she showed up in the pages of newspapers across the country this week, she looked utterly winsome and holy. Kateri Tekakwitha, a 17th-century Mohawk Indian and Catholic convert, clutches a crucifix to her breast in many of the illustrations. She gazes skyward beneath long, lovely lashes. She is garlanded by flowers. A tiny halo encircles her glossy black hair, and we’re not surprised to read that this week Pope Benedict XVI credited Kateri with a new miracle. The pope decided that when Catholics prayed to her in 2006, she in turn lobbied God to spare the life a 6-year-old American Indian boy, Jake Finkbonner, who was being ravaged by a flesh-eating bacterial disease.

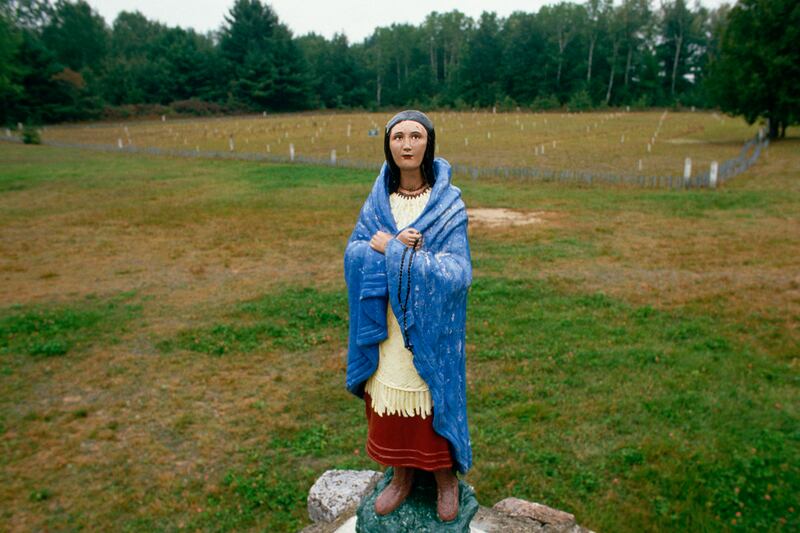

Soon—probably next October—Kateri will be canonized. She will join the church’s list of 1,500 or so Vatican-recognized saints. She will become our nation’s first American Indian saint—and almost certainly images of a beguiling and pious Native maiden will proliferate on prayer cards and in the little niches where churches keep their statues of saints. In the mythology of the Catholic Church, Kateri is “The Lily of the Mohawks.” She is a serene and almost otherworldly icon of purity.

Which is a shame because Kateri Tekakwitha (1656-1680) was a flesh-and-blood historical figure whose life was far more interesting—and far more complex and shadowed—than the charming Christmas miracle tale being broadcast by USA Today and other media.

Kateri lived in what is now upstate New York and Quebec as French immigrants were Christianizing the region and warring with the five eastern bands of the Iroquois, including the Mohawks. When she was 4, she contracted smallpox. The disease left her almost blind. Her parents and her brother died in the same epidemic.

Meanwhile, in 1665, a leading French general, Alexandre de Prouville, arrived in New France. As church bells pealed in Quebec City, the bishop of the colony received de Prouville at the entrance of the local church. He offered the general holy water and led him to his own clerical prayer stool. The following year, de Prouville burned down Kateri’s village as she and others took refuge in the woods.

It was in this manner that the Jesuits gained entrée to the Iroquois settlements. Kateri’s uncle and guardian didn’t want her to convert, and through most of her teens, she steered clear of the priests. But then, one spring day when she was 18, a Jesuit father happened by her cabin and charmed her. “The first words that Catherine [the Jesuits’ name for Kateri] spoke to the father revealed the feelings in her heart,” wrote Claude Chauchetière, a 17th-century French Jesuit.

After she converted to Catholicism, Kateri had a friend whip her almost daily so that she could experience the agony that Christ felt on the cross. She put hot coals between her toes. She shunned men and sex. She spent much of her last years lying in a bark-covered longhouse, sick with fever. Yet she still fasted, in penitence, and ministered to other sick people and to the elderly.

There were about a dozen Native ascetics in Kateri’s village, all of them women, but Kateri was “the most fervent,” according to another Jesuit priest, Pierre Cholonec. She exuded a “sacred fire,” and early in 1680, when she was wracked with a fever, she elected to sleep for three successive nights on a bed of thorns. The ordeal may have quickened her death, which came that April.

Why aren’t we reading about Kateri’s anguished trials in the news this week? In part because the Vatican is masterful at public relations. The Vatican has known about Kateri for centuries and been aware of Jake Finkbonner’s sudden cure since at least 2008. But did Pope Benedict confirm the miracle on the anniversary of General de Prouville’s bonfire? Or on Canadian Thanksgiving? No, he chose to celebrate the recovery of a small boy at Christmastime. So we have a made-for-TV holiday tale: Jake Finkbonner, now 11, is Tiny Tim, and the darker narrative, the war with the Iroquois, slides into the background, as do the problems that Pope Benedict, calcified and old school in his politics, is promulgating right now. In the 21st century, should the Catholic Church still be telling AIDS-afflicted Africa that condoms are evil? Should it still be regarding women as incapable of serving as priests?

Benedict is by no means solely responsible for sugarcoating Kateri, though. The Catholic Church’s saints are almost inherently kitsch. They are real people who’ve been turned into statues and miniaturized so they can be sold in the gift shop. Kateri is hardly the first saint whose bio has been conveniently tweaked. Consider Saint Francis of Assisi, the patron saint of animals. Day to day, Francis was a righteous jerk. Once, when a fellow friar happened to chat with some nuns, Francis told the guy that “the company of women is poisoned honey” and forced him to jump into the freezing river as penance. We remember Francis as gentle in part because in 1236, just 10 years after his death, a British monk named Roger of Wendover wrote a story about a sweet-voiced saint who induced the birds to rest on his arms and shoulders.

Of course, mythmaking isn’t endemic to the Catholic Church. We inflate our secular heroes too—John F. Kennedy wasn’t really a Camelotian prince. And perhaps what’s most important now, as the Kateri story breaks, is that we embrace the saints for being both holy and human. They lived, as all of us do, amid the weather and hardship of everyday life, and yet they did extraordinary things.

My own favorite saint is Saint Martin of Tours, a 4th-century Gallic bishop who I know about mostly from long-ago homilies written by my uncle, a Catholic monk and priest. Martin lived, my uncle wrote, “just as the Church was first falling prey to an unholy union of irresponsible political power and ecclesiastical authority. Martin was made a bishop against the opposition of those who objected to his unconventional dress and behavior, and as bishop he would not live in a palace or wear fine clothing.” When other bishops allied with western Rome’s emperor, Maximus, to have a rival religious leader put to death for heresy, “Saint Martin objected strenuously,” my uncle wrote. “Moreover, Saint Martin went to Trier and confronted the emperor.”

Saint Martin was a hero. He took action. And Kateri did as well. She found in Catholicism a new calling and—even though her life had been broken by war and by illness—she followed her path, with devotion and fortitude. In these darkest days of the year, as we search for light and hope, we can find it shining out in the miracle of Kateri Tekakwitha’s passionate living.