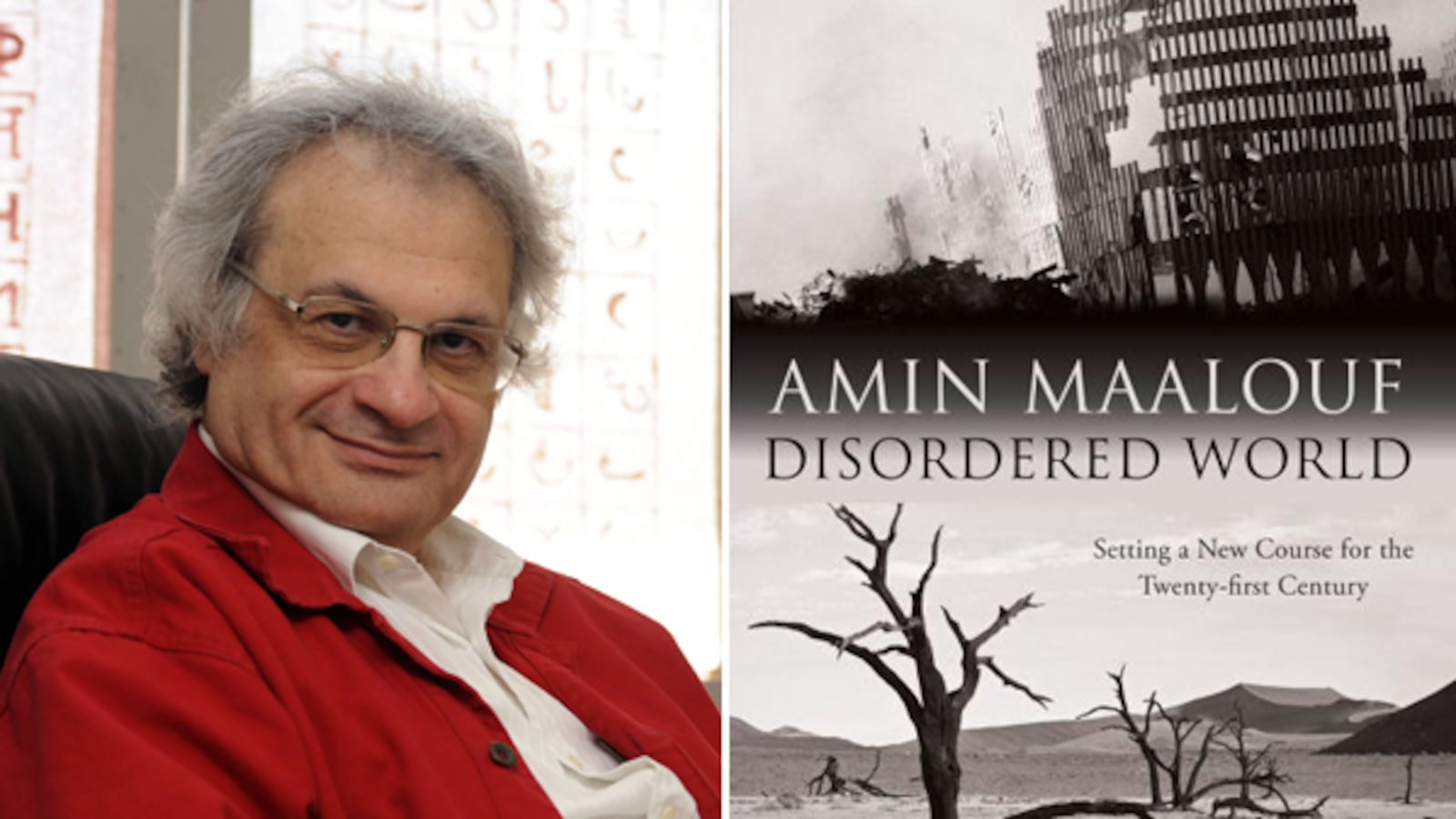

You wouldn’t know it to hold Disordered World in your hands, but it’s a big book. Subtitled “Setting a New Course for the Twenty-first Century,” this nonfiction offering by Amin Maalouf (famed Lebanese-French author of novels such as Leo Africanus, The Rock of Tanios, and Balthasar’s Odyssey) not only attempts to pinpoint when, how, and why humanity went astray; it assumes the ambitious task of outlining the means by which the world might be restored to its proper trajectory. This is precisely the sort of undertaking to provoke a snicker on the part of the cynical and a pitying shake of the head on the part of the pessimistic. But Maalouf is so earnest, and his arguments so cogent, that he may well convince the doubters, or at least briefly silence their naysaying.

So, what’s wrong with the world? Climate change, for starters. In Maalouf’s view, this is the biggest threat to earth and humanity. Yet perhaps inevitably, given the extensive news coverage of the issue, those sections of the book in which Maalouf discusses climate change feel overly familiar.

Far more original are Maalouf’s views on how belligerence has increasingly come to inhere in contemporary religious and other identities. You might expect as much from the author of In the Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong. But Maalouf’s thoughts on this subject have probably influenced—to one extent or another—his entire oeuvre, most of which is fiction. Essentially, Maalouf has been warming up to write Disordered World for quite some time. And in a way, this nonfiction book serves as an exegesis of Maalouf’s sprawling historical fiction, spelling out the beliefs and values he has interwoven into his novels, and hinted at wanting to disseminate among humankind.

Nevertheless, the author is not one to write in a theoretical manner detached from the sociopolitical realities of his day. The beginning of the 21st century is a propitious time for the publication of such a book, and Maalouf keeps his discussion firmly rooted in contemporary history. He believes that the end of the Cold War, which could have ushered in an age of peace and prosperity, served instead to multiply differences between people. This was due principally to a resurgence in the importance of ancestral ethno-religious identities and concomitant “inherited allegiances,” which filled the vacuum left by a half-century-long conflict that promptly petered out. He notes that “with the end of bipolar confrontation we went from a world in which divisions were mainly ideological and the debate incessant to a world in which the divisions mainly concern identity and leave little room for debate.” Maalouf goes so far as to lament the coincidental rise of the internet during this time, as he believes it exacerbated matters by creating “global tribes” of transnational communities.

Unfortunately, because the book was written before the Arab Spring (it was published in French in 2009), the author’s almost uniformly gloomy picture of the Arab world is dated. (His occasional lazy generalizations regarding a supposed Arab psyche are also not of much use.) Nevertheless, those parts of the book focusing on Arab history and politics include a couple of fascinating segments, especially a discussion of leadership and legitimacy, and (slightly fanciful) musings regarding the possible benefits of having a Muslim pope, whose centralized authority would in Maalouf’s view ensure the entire Muslim world’s progress.

Perhaps the most important part of Disordered World is the author’s discussion of culture and universal values. Maalouf is no retrospective imperialist, yet he does imply that he might have judged European imperialism differently had it been underlain not by economic avarice and strategic considerations, but by a missionary desire to spread humane socio-political values. “Contrary to the received idea,” he asserts, “the perennial fault of the European powers is not that they wanted to impose their values on the rest of the world, but precisely the opposite: it is that they have constantly renounced their own values in their dealings with the peoples they have dominated.”

Maalouf points out that things are not much different today. Indeed, installing democracy in Iraq was an afterthought on the part of the George W. Bush presidential administration. But it is in a certain understanding of multiculturalism that the double standards of ostensibly egalitarian Westerners manifest themselves most starkly. Acquiescing in non-Westerners’ inegalitarian treatment of women or minorities, while intended as a mark of respect, strikes Maalouf as contemptuous in the extreme, and reminiscent of European imperialists’ idea that natives do not deserve the same rights as Europeans. In a hugely important and necessary move, he challenges Westerners to stop viewing Islam as the be all and end all of a Muslim’s identity, and expresses alarm at the tendency of many in Europe to almost forcibly bind nominally Muslim immigrants to archaically minded Muslim clerics and self-appointed community leaders. Ultimately, he makes it clear that his notion of respecting a culture consists of exploring what it has to offer in the way of literature and the arts—in which may be found elements of universalism—but not condoning any form of bigotry or discrimination.

Crucially, in Maalouf’s view, when it comes to building bridges between people, the onus does not fall on the host countries, despite their responsibilities toward immigrants. In the struggle for social harmony in a globalized world, the immigrants will have to take the lead. Maalouf sees redemption through cultural understanding, and specifically through the learning of languages. “Religious identity is exclusive; linguistic identity is not,” he points out. It follows that he considers the immigrant the primary agent through which the desired change can be realized. Every immigrant is also an emigrant, he reminds readers, meaning that an immigrant has a head-start when it comes to achieving the biculturalism he views as the surest way to break down barriers between people. He does not like the British approach to immigrants, which allows them to retain their culture but views them as constituents of communities separate from the main populace, and is uncomfortable with the French model, which accepts immigrants into French society so long as they shed their original culture. “[I]n spite of their differences,” Maalouf observes, “these two policies start from the same supposition, namely that a person cannot belong fully to two cultures at once.”

Looking at the world today, one cannot but conclude that the arena in which Maalouf’s prized biculturalism could best be nurtured is the West. The countries of the Arab-Muslim world do not play host to sizable numbers of immigrants—only migrant workers and refugees. Not only that, but many Arab and Muslim countries display a marked demographic trend toward religious (and ethnic) homogenization. In other words, the non-Muslim minorities are leaving (and sometimes being pushed out) en masse.

Maalouf, who was born in Beirut to Lebanese Christian parents, does not shy away from this sensitive subject. He laments the plight of non-Muslim minorities in Iraq today, highlighting that of the Mandaeans, and reminds readers of the fate of Jews across the Arab world in recent decades. Addressing the contemporary situation of Christians in Arab countries, he observes: “Having become strangers in their own land, despite living there for centuries and sometimes even millennia, several of these communities will disappear in the course of the next twenty years, without it causing much distress among their Muslim compatriots or their fellow Christians in the West.”

There is a cruel irony to this story. Following the leading role played by Levantine Christians in the Arab literary and cultural renaissance (nahda) of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which was set in motion by Egyptians’ contact with French and British colonial powers and furthered by Levantines’ contact with American Protestant missionaries, a newer crop of Levantine Christians set their sights on the West itself. Beginning in the early 20th century, westernized intellectuals, historians, and political activists from the Levant came to serve as ambassadors of the Arab world, explaining to Westerners the finer points of Arab culture and the Muslim religion, lobbying for Arab political causes, and even defending Islam.

The phenomenon these men embodied continued into the latter half of the 20th century. Like fellow historian Philip Hitti, who established the first Middle East studies center in the United States (Princeton University’s Program in Near Eastern Studies, inaugurated in 1947), Albert Hourani was only briefly involved in political advocacy (in his case at the start of his career in the late 1940s), but through his academic work, he deepened the West’s understanding of Arabs and their past. Think also of a man cut from a different cloth: literary and cultural critic Edward Said, stalwart defender of the Palestinian cause and vehement opponent of generalized, widespread, and often condescending assumptions concerning Arabs and Islam.

The (moderate) successes of these Christian Arabs in changing Westerners’ negative perceptions of Arabs were due in part to their considerable intellect and erudition. But their achievements also owed something to provincial Westerners’ need to see a bit of themselves in Arabs in order to sympathize with them—that’s where their Christian identity and facility with Western languages came in handy. With time, as western education spread among middle-class Muslims in the Arab world, and as the West began to feel more comfortable with its post-Christian identity, the value of this previously indispensable species of interlocutor began to diminish. After all, Westerners and Muslim Arabs could now communicate directly.

As the 20th century ground on, Christians started to leave the Arab world in droves. Lack of economic opportunity, political autocracy, the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Lebanese civil war, Islamic fundamentalism, the Iraq wars and sanctions, and a steadily decreasing birthrate among the increasingly middle-class Christians made this inevitable. Today, the question is no longer whether Christian Arabs and non-Arab Christians in the region will find new ways to earn cultural prestige, but whether their communities will continue to exist in sizable numbers. With a paradoxical mixture of resignation and stoicism, Maalouf declares: “I in fact belong to a species which is headed for extinction, and I will refuse to my dying breath to consider as normal the emergence of a world in which communities which have lasted for millennia, and which are guardians of the most ancient of human societies, are forced to pack up and abandon their ancestral homes to seek refuge in foreign lands.”

Maalouf’s book, written in French and now very ably translated into English by George Miller, may well conclude a lengthy and important historical episode. Maalouf, of course, will continue to be a fine novelist and occasional essayist. And the future of Christians in the Arab world may not be quite as bleak as he predicts. But an era that enabled his role as cultural interlocutor (recall that his first book was The Crusades Through Arab Eyes) has likely come to an end. For some years now, there have been Muslims writing major works in European languages about the challenges involved in integrating large numbers of their coreligionists into western societies. Disordered World is a swansong of sorts. It is a remarkable book dedicated in large part to convincing Westerners of the worth of Muslim and other immigrants, written by a man who represents the tail end of a noble century-long attempt by Christian Arabs to convince the West of the worth of Arabs and Islam.