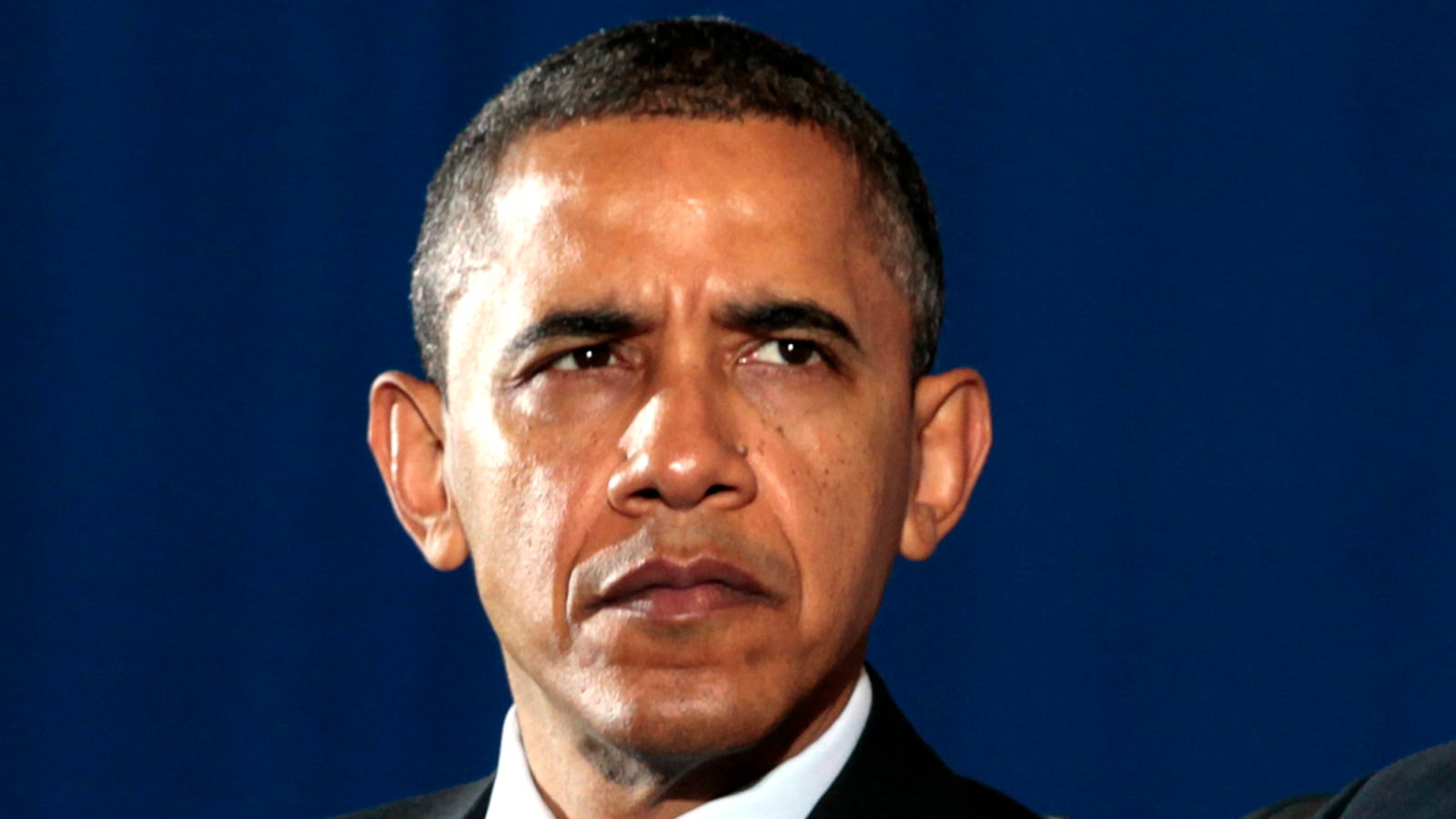

The American people are deeply frustrated with elected officials in Washington, D.C., right now. But imagine if the Republicans retake the U.S. senate and President Obama squeaks out a narrow no-mandate reelection victory?

Will we be destined to witness endless partisan brinksmanship and “small-ball” incrementalism? Will our incapacity to govern efficiently and effectively further weaken our image as a global leader? What will this mean for urgently needed tax reform and creative debt-reduction initiatives?

It’s time to start thinking about these questions and possibilities, for the Democrats’ hold on the U.S. Senate is tenuous. Democrats lost six seats in the last cycle, counting Scott Brown’s special-election win in Massachusetts—leaving them well short of the 60-seat “supermajority” needed to pass major and, of late, even ordinary legislation. This November, with 23 seats to defend compared with 10 for Republicans, they risk further losses in tough races in Nebraska, North Dakota, Missouri, Montana, Virginia, and elsewhere.

Sure, the Democrats might pick up a seat or two elsewhere, but they can’t bank on this, and just a four-seat swing would shift control to the GOP.

Meantime, President Obama’s coattails have been notably short, if not nonexistent, since 2010. Remember Ted Kennedy’s seat? Obama’s seat? Anthony Weiner’s House seat? And of course the Tea Party blowback year in 2010?

Can a second term get worse for Obama? For America? History instructs that second terms are marked by more trials and disappointments than triumphs.

Quick: Name the two-term presidents whose second terms were measurably better than their first terms? A few such as Washington, Andrew Jackson, and Teddy Roosevelt might qualify, but this is going back a ways.

Second terms in the past hundred years have been problematic. Wilson had a stroke and became both a physical and political invalid. FDR’s second term was his least successful (his third term was an exception in so many ways). Nixon was thrown out. Clinton was impeached.

Eisenhower and Reagan had decent seconds terms yet by no means as successful as their first ones. George W. Bush’s later trials and tribulations were the very definition of second-term blues.

The 22nd Amendment, limiting presidents to two terms, has the effect, or so many people believe, of having the sun starting to set forever the very day a president’s second term begins.

So what are chances for leadership in Washington come 2013? For an embrace of the Simpson-Bowles commission plan for debt reduction and a streamlining of the U.S. tax codes? For responsible immigration reform and smart investments in making Americans more innovative and more competitive?

One of Obama’s best hopes for implementing such changes should he win reelection, paradoxically, is that voters, even as they continue to embark on yet another anti-Washington “wave election,” may decide that they will reluctantly retain Obama because next summer’s political forecasts predict a Congress wholly controlled by Republicans to go along with the already red-leaning Supreme Court. Americans like mixed government, and enough people could split their tickets to make this happen.

Conventional wisdom suggests we’ll have a lot more gridlock in this scenario—that senators will continue to hold up presidential appointments, House leaders to hold the president over a barrel of artificial deadline crises and short-term budget deals, and the president to try and bypass Congress by governing when possible through executive orders.

But some presidents have defied the odds of dealing with an opposition-controlled Congress in their second terms. Eisenhower and Congress worked to enact the Interstate Highway System. Reagan helped broker with Congress a reasonably important (at the time) tax-reform act in 1986. Clinton, even with Gingrich riding high in Congress, made progress on budget and debt issues.

Our presidential-congressional separation-of-powers system has traditionally moved slowly, and typically becomes bold only in response to crises. That’s the way it was designed. “Where the country is not sure what ought to be done,” wrote historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., “it may be that delay, debate and further consideration are not a bad idea. And if our leadership is sure what to do, it must educate the rest of us—and that is not a bad idea either.”

Presidents, working even with a Congress wholly controlled by the other party, can get important measures passed. The key in almost every case is that a competent teaching president figured out what needed to be done and then creatively collaborated and compromised with the Congress and persuaded the American people about the merits of the proposed action.

The presidency often seems an impossible or near-impossible job. It has humbled most of its occupants.

But 21st-century America requires presidential leadership. The only way to reduce the need for a strong presidency is to adopt the Ron Paul politics of greatly reducing America’s role in the world, retreat from global economic leadership, and dramatically reduce the size of government. Some people favor this. But this is not going to happen.