The literary anthology has long been a tool for herding together a group of like-minded writers or themed stories, but in recent years, we’ve seen something different: the appearance of anthologies devoted to some political or social cause. The organization Words Without Borders, which is dedicated to promoting literature-in-translation, is in the vanguard of this movement, producing anthologies of fiction from the Muslim world and the so-called Axis of Evil countries, as well as one commemorating the fall of the Berlin Wall. These are books with a thesis behind them, but it’s one not so different from a fundamental aspect of fiction itself: that is, they help to make the world a smaller place.

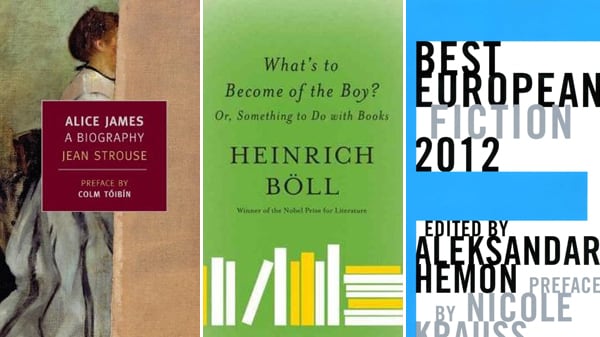

Dalkey Archive’s Best European Fiction series, now entering its third year, belongs more in the Words Without Borders camp than, say, Akashic’s anthologies of noir fiction, each of which is set in a particular city, from Mumbai to San Diego. Best European Fiction 2012, whose latest edition is attentively edited, like its forebears, by Aleksandar Hemon, is fiction as cultural ambassador. It aims to open readers’ well-guarded gates to work from far-flung writers, to show that these ostensibly exotic imports both have something vital to say and are, in the end, not so different from the writers we treasure at home. Hemon’s book is also a responsum to the oft-cited lament (one that frankly has been leaned on too much by certain members of the critical establishment) that, depending on the figures one uses, only 3 percent or less of fiction published in the United States has been translated from a foreign language.

The problem with these sorts of anthologies is that they are often given credit simply for showing up. Their conceit is so obviously admirable—who would refuse to read a more human, less politicized depiction of life in Tehran or Moscow?—that they tend to pass through reviewers’ hands with the kind of pat affirmations that are better suited to cheering on a child’s struggling Little League team. Great try!

That is a preamble to say that there is much to admire about Hemon’s choices for this anthology, but some of them do fall flat. “The Owners,” Serhiy Zhadan’s comic tale of (heterosexual) mobsters opening a gay club in Kharkiv, Ukraine, has some funny moments, such as when one character disbelievingly asks whether a band as famous as U2 actually played in Kharkiv (they canceled). But the story, which tries to lodge an attack on homophobia in Ukrainian society, relies too much on the inherent novelty of these men running a gay club. When one of the owners hits on a woman who turns out to be a lesbian, her response—“Don’t you get it? I’m a lesbian. And you aren’t even gay. You’re just the owner. You know what I mean?”—seems like an outtake from a mid-'90s American sitcom. In the end, the story is more interesting for how it shows a culture debating, however awkwardly, certain cultural mores.

“The Owners,” though, is one of only a few weak selections in the book. Zhadan’s story does leave one wanting more of his humorous take on the Ukrainian underworld. And while many of the anthology’s stories could, with a bit of fiddling with the details, take place in the United States, “The Owners” is a reminder that fiction sometimes should knock us off-kilter, if not emotionally then by causing us to ask, What’s going on here? Why doesn’t it seem to work? What, in turn, might that say about us?

Part of the pleasure of Best European Fiction 2012 is that process of socio-cultural comparison. The stories are organized by broad categories—crime, war, love, art—and each lists the writer’s home country and the story’s original language. Rarely does one get to read a story originally written in Serbian, much less Rhaeto-Romanic or Galician. Writers who choose to compose in minority or embattled languages, like Gabriel Rosenstock (Irish), deserve special praise, both because their linguistic choices represent an attempt to ensure a culture’s survival and because, ultimately and more importantly, their work is so good.

Publishers, then, should turn to this collection as a kind of farm system from which to draft future stars. But readers should too. Whether it’s Jiri Kratochvil’s World War II story narrated by a Soviet cavalry horse; Armin Koomagi’s report from a support group called Logisticians Anonymous; or Patrick Bolthauser’s unexpectedly stirring, second-person story about a family outing, there’s profit here.

We can never quite be done with World War II. Every updated history and culminating analysis—no matter how convincing—leaves an unresolved sourness hanging in the air. Heinrich Böll’s What’s to Become of the Boy? Or, Something to Do With Books, translated by Leila Vennewitz and just released by Melville House, recalls what it was like to have been a schoolboy in Germany as the sour cloud of Nazism descended. “[I]t was a matter not of après nous but avant nous le déluge,” Böll writes in the slender memoir of his high-school years between 1933 and 1937.

Böll recounts this time in a series of overlapping vignettes that combine nostalgia with a wakening sense of the political miasma seeping through the cracks. His reveries do not enumerate the conditions and methods that brought Nazism to majority rule, but instead describe how his youthful interest in Latin, sex, and bicycle riding as oppressively intruded upon by them. “The Nazis had become an eternity,” Böll writes, “the war was to become one, and war plus Nazis were a double eternity—yet I wanted to try to live beyond those four eternities.”

Böll’s family was lower-middle class; neither mother nor father had gotten past elementary school. His father made money doing odd jobs in a workshop and renting out spare rooms in the family home. The family lived with a contradictory sense of parsimony and indulgence, “both beyond and below our means.” Since so many basic necessities depended on lines of credit with local merchants—the distorting effect of a decade of incomprehensible hyperinflation—they scrounged to pay the electric bill and buy groceries and yet indulged in calculated bourgeois luxuries of movie tickets, coffee, and fresh rolls with boiled ham.

Böll came to love literature and language study, especially lessons in Latin and Greek. He found himself bored by the slow proctoring of school sessions and often favored reading ahead in the evenings, ditching class to wander the streets of Cologne, imagining himself a traveler without luggage (from Jean Anouilh’s play of the same name). By his own estimate, Böll spent only half his days in school, with the remainder dedicated to roaming, reading, and bartering with locals for the packed French cigarettes that the Nazis would soon prohibit.

Böll describes the aftereffects of the execution of the Communist conspirators blamed for the Reichstag fire in 1933 as producing fear and shock, “the kind that before a thunderstorm makes birds flutter up into the sky and seek shelter.” In the months following the formation of a Nazi-centered coalition government, the effects of militarization and social scapegoating began to pock Cologne. “The non-symbolic purges were visible and audible,” Böll remembers, as the Nazis rounded up political opponents in the Communist and Social Democratic parties, “expressions such as ‘protective custody’ and ‘shot while trying to escape’ became familiar; even some of my father’s friends were caught in the process, men who later, on their return, maintained a stony silence.”

As with Victor Klemperer’s mesmerizing diaries, Böll’s recounting provokes a frustration that no one seemed more inclined to forgo their daily struggles to do something to resist the coming deluge. Böll does not avoid the question but earns an extraordinary amount of sympathy for how overwhelmingly difficult a task it would have been in context. He recalls why his family hadn’t even considered emigrating: “we found it hard to explain that such an idea was simply beyond the realm of our imagination: it was as if someone had asked why I hadn’t ordered a taxi to the moon.”

What’s to Become of the Boy? is a remembrance without forgiveness, neither for its author nor the villains that darkened the crevices of his childhood. It makes a beautifully lucid case for politics as the antithesis of beauty in human life. The two cannot be separated, but they repel one another. The areas where they overlap are cryptically blurred, impossible to anticipate what monstrosities might come from them.

The book closes with an ominous description of Böll’s final exams in his last year of school. Biology was the only mandatory subject for all students. The exam entailed circling with red, white, and pink chalk genetic pairs based on the work of Gregor Mendel, the Austrian founder of genetic theory. In closing Böll wonders, “in how many thousands of schools—and not only during final exams—was Mendelian pink drawn on the blackboard by how many hundreds of thousands of students?” We know what became of Böll, and we have some idea of what those other hundreds of thousands of students did with their heads full of Mendelian genetics, too. The deluge eventually came and the question was no longer how to prevent it, but simply how to survive—the paradoxical point at which the boy became a man.

—Michael Thomsen

In Susan Sontag’s 1993 play Alice in Bed, the bed-ridden neurasthenic sister of William and Henry James proclaims: “I have these grand thoughts, moments when my mind is flooded by a luminous wave that fills me with the sense of potency or vitality of understanding, and I feel I’ve pierced the mystery of the universe, and then it’s time for an emetic or to have my hair brushed or a sheet changed.” The contrast between Alice James’s potential for genius and the limitations placed on it is the central theme of Jean Strouse’s biography, originally published in 1980 and reissued recently by NYRB Classics.

Alice James (1848-1892) was the last-born child to a distinguished, well-off, yet deeply bizarre family; her father, Henry James Senior, was a religious yet practical man who believed in children’s “divinely endowed natural instincts,” and who once gave his daughter permission to kill herself. Her mother, Mary James, was the embodiment of Virginia Woolf’s Angel in the House, yet she did not believe that “her children should disturb her sleep at night.” Alice James, in the diary that would make her a feminist icon a century after her death, often wrote that there was never enough love in the family to trickle down to her. In her well-researched, excellently contextualized biography of James, Jean Strouse calls this the “bank-account theory of family intelligence” and health: when some James children were succeeding, others were floundering; when some were well, others were sick. Strouse’s biography devotes much room to this oddly symbiotic relationship among the James siblings, and contends that as the only daughter in the family, Alice was always fighting for more than what she got.

Throughout her life, James would suffer numerous psychological and physical breakdowns, leading to a diagnosis of hysteria, for which she received the standard range of eccentric Victorian treatments: the rest cure and the exercise cure, the massage cure and an early version of electroshock therapy.

Her invalidism kept her in a constant state of “potent capacity.” Henry James’s description of Winterbourne’s aunt in Daisy Miller is bitterly apt: “Mrs Costello was a widow of fortune, a person of much distinction, and who frequently intimated that if she hadn’t been so dreadfully liable to sick-headaches she would probably have left a deeper impress on her time.”

What Henry James could not know was that it was precisely because of these “sick-headaches” that his sister would become a feminist icon, and leave an impress if not on her own time, then on times to come. In 1889, Alice James began to keep a diary, which was published after her death, and in which she recounts the distance between her family’s view of her and her view of herself.

Strouse lays the blame for James’s mental illness partly on her epoch and partly on her family. It was not the most beneficial of environments for a little girl to grow up in, or even for an effeminate little boy: the young William James refused to play with his little brother Henry, claiming: “I play with boys who curse and swear!” Alice’s education was, she said later, “accidental”: it was never a priority for her family. She herself was self-deprecating in the extreme, signing letters to her brothers “your idiotoid sister, Alice.” Strouse shows Alice outwardly accepting her role in the family hierarchy, but inwardly fighting it, and it is to this attempt to repress these violent feelings that Strouse attributes James’s mental illness. James described herself as “an emotional volcano,” and said that writing her diary provided her with “an outlet to that geyser of emotions, sensations, speculations and reflections which ferments perpetually.” One of Alice’s doctors, the 19th-century physician Charles Fayette Taylor, prescribed an exercise cure for James, claiming that hysterical women who were overexcited by intellectual and emotional stimulation needed an outlet for their excitement. Strouse tells us that while Taylor was wrong about many things (notably the adverse effects of education on women), he was right about the need for “some kind of release from brooding self-absorption.” For James, the diary was that release.

But for someone so well-known as a diarist, we hear remarkably little from Alice herself. Strouse renders Alice’s internal life in only the most general terms, so that it is difficult to develop anything more than an impersonal sympathy for James. More use could have been made of James’s diary, which we learn “shows Alice groping to find a voice in which to talk about her private experience and the world around her.” Nevertheless, Strouse writes, the diary “conceals as much as it reveals.” The same could be said for Strouse’s biography.

—Lauren Elkin