At a fashionable art gallery in New York City, the work of a mysterious psychiatrist who practiced in the 1940s is getting a second life.

In the exhibit Free Associations, now at the Lori Bookstein Fine Art gallery, the artist, author, and New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm has created a beguiling array of collages of the unknown psychiatrist’s work. In a statement posted in the gallery, she says simply, “Last winter, I came into possession of the papers of an émigré psychiatrist who practiced in New York in the late 1940s and 1950s.”

Malcolm goes on to describe the psychiatric case notes she unearthed—notes that caused, as she puts it, her “collagist’s imagination to stir.” Indeed, it’s hard to resist the mysterious case notes, with their staccato descriptions of long-gone anxieties.

Says one typewritten vignette: “Feels worse—desperate—last week felt there is some progress—yesterday and today just wretched—feels worst than when he first saw me.”

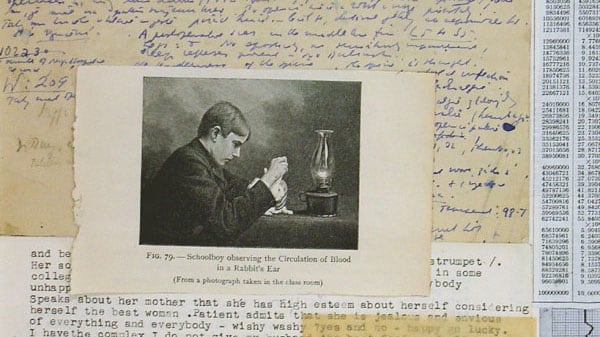

Accompanying the words in these collages are images in musty, muted colors: old-fashioned pictures, and index cards with the names of strange neurological diagnoses: “Ouch ouch disease.” “Maple syrup disease.“

In one collage, there’s a faded photograph taken at Marienbad, an old Czech spa. (Malcolm herself was born in Prague.) In the photo, a group of men lounge by a water fountain, some in full suits, others in elegant striped bathrobes.

“There’s something so wonderfully preposterous about these guys,” she says, laughing. “I just love this picture.” The photograph comes from a book a friend sent her years ago, a book of communist imagery and glorified visions of Iron Curtain Eastern Europe. She clipped out the photo and tucked it away, waiting to find just the right place for it.

Freudian terms—“externalization,” “hysterical anesthesia”— snake their way through the collages in this show’s yellowed, bygone aesthetic.

Malcolm has written two books about psychoanalysis, both published in the 1980s. In one, Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession, she describes psychoanalysis as a “system of thought … which has detonated throughout the intellectual, social, artistic, and ordinary life of our century as no cultural force has … since Christianity. The fallout from this bomb has yet to settle.”

But, in a sense, it’s not surprising that Malcolm has found such a natural second form in collage.

Her writing has always reflected a similar instinct.

Last year, in her unforgettable New Yorker piece, Iphigenia in Forest Hills—Malcolm’s account of the murder trial of Mazoltuv Borkukhova—there is a moment that leaps off the page.

In the midst of the trial, Malcolm receives an unexpected phone call one evening. It's from a legal guardian who had delivered a key piece of testimony during the proceedings. What he says is even more surprising than the fact that he's called at all. Malcolm summarizes the crazed spiel with a list:

“Banks do not lend money. They have no money.All of the banks are zombie banks.The system is run by useful idiots.We need enemies.There will be genocidal austerity.”

The list stretches on and on. It’s a pivotal moment in the unfolding drama of the piece. But it’s Malcolm’s technique that makes the passage so memorable.

We get the man’s deep-dyed peculiarities, but we also get what it is to be the journalist on the receiving end of the phone call, caught without her tape recorder, nothing to do but to snatch up the central bits and pieces of what is being said.

It turns out that the bits and pieces woven together in this way tell more than the full story.

Malcolm does not often give interviews. Earlier this year, when she was the subject of The Paris Review’s storied series of writers on writing, Malcolm provided most of her answers via email. But she agreed to meet to discuss her collages.

Malcolm lives in New York, in an apartment of wood floors and oriental carpets, overlooking Gramercy Park. She is small and feline and elegantly dressed; she answers every question with thought.

Her current show raises an obvious question: whose case notes were these? Who exactly is this émigré psychiatrist whose original writings, both handwritten and typed, Malcolm has disassembled, cut, pasted, and reassembled, in this fascinating display?

“I’ve decided I’d like to keep that kind of a little bit vague and mysterious,” Malcolm says in reply.

One doesn't necessarily want to pry.

However, it’s no secret that Malcolm’s father was an émigré psychiatrist and neurologist who practiced in New York in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Make of that what you will.

The show “Free Associations” runs through Jan. 14 at Lori Bookstein Fine Art, 138 Tenth Avenue in New York City.