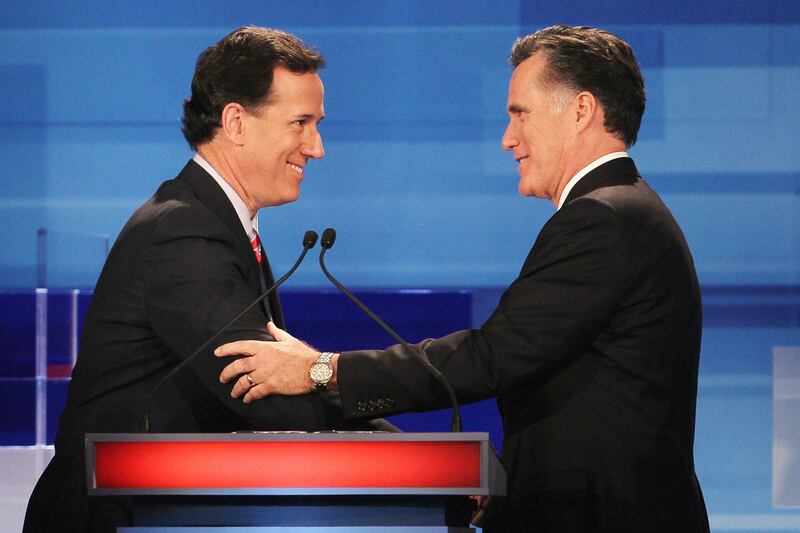

Rick Santorum finished a mere eight votes behind Mitt Romney in the nail-biting Iowa caucuses, catapulting himself from nowhere into a virtual tie that defied the professional prognosticators.

As recently as two weeks ago, almost no one in the political and media establishment gave the underfunded ex-senator much of a chance to win the first presidential contest of 2012. Now, after Tuesday night, Santorum is the story.

With Romney pulling 30,015 votes and Santorum 30,007—both at 24.6 percent—it was a cliffhanger dulled only by the fact that bragging rights, not delegates, were at stake. Romney survived a tough state for him, one in which he barely campaigned, and is in a commanding position to win New Hampshire next week.

On the flipside, Romney, with a huge financial advantage, failed to draw more than a quarter of the voters—just like 2008—and lucked out with two other contenders splitting the bulk of the conservative vote. He doesn’t get much of a bump.

And while the little-known Santorum will be flooded with donations as he tries to gear up for the coming contests, he will face a wave of attacks and media frisking that he dodged in Iowa by surging so late. What’s more, the evangelical Christian vote—Santorum captured a third, according to entrance polls—won’t be as large in other contests. (He thanked his wife and God, in that order, in his post-midnight speech.)

In the end, the results were rather muddled: Romney won with the lowest percentage in GOP-caucus history, breaking Bob Dole’s record from 1996.

In placing a strong third with 21 percent, Ron Paul went from fringe character four years ago to solid candidate this time, despite some out-there views and a newsletter controversy that would have sunk just about anyone else.

The Paul bubble lost a bit of air after it briefly seemed he might win the caucuses. His campaign was perfectly constructed for Iowa, but he’s unlikely to play as well elsewhere. Some of the obscure lines in his gold-standard speech to supporters—“We’re all Austrians now”—underscored the oddball nature of his adventure.

Fourth place usually doesn’t mean squat in Iowa, but in this case it does. By squeaking past the bottom tier with 13 percent of the vote, Newt Gingrich stays alive, if just barely, and made clear he’s going to make life hell for Mitt. (He told supporters that “we survived”—before savaging Romney for a record of managing “decay.”)

Rick Perry skidded to an embarrassing fifth-place showing, with 10 percent, after once leading the field, and all but signaled he is dropping out. When a politician says he’s going home to “assess” the results, as Perry did Tuesday night, that’s code for folding his campaign.

Michele Bachmann placed last, with 5 percent, a stunning fall for the woman who won the Ames straw poll, which should now be dismissed as the joke it is.

You can make the case that Romney should have won easily, that he’s been running for president for five years, had a big chunk of the establishment behind him and a well-oiled campaign apparatus. But Romney didn’t really play in Iowa until the end, when he stumbled by predicting he would win. His Mormon religion remained a problem for some evangelical voters, who wield an outsize influence in Iowa. And he’s not exactly Mr. Excitement.

You also can make the case that Santorum had no business finishing at the top. He’s a somewhat dour campaigner who talks like a legislator and got clobbered by 18 points in his last Senate race. But even if he was the last plausible not-Romney standing in a field of flameouts, his perseverance paid off.

The questions now are as numerous as they are difficult to answer:

Will Bachmann join Perry in packing it up? She has to worry about hanging onto her House seat, just as Perry, as a sitting governor who jumped in late, doesn’t want to be unduly embarrassed in front of his fellow Texans. Paul, for his part, has no reason to drop out, since he sees himself as leading a movement and can always raise adequate cash online.

Will Gingrich, an experienced attack dog, draw blood by biting Romney as a “Massachusetts moderate”—even if his own chances of winning the nomination are fading? Revenge can be a powerful motivator in politics. Neutron Newt could do serious damage.

Will social conservatives now rally around Santorum? Does he have enough pizzazz to broaden his base and enough agility to survive the coming wave of opposition attacks?

Can Romney rally support from conservatives who aren’t wild about him but want to evict Barack Obama? Can the electability argument attract those who had their hearts set on more right-wing rivals?

Perhaps it doesn’t matter, as it’s hard to see who can go the distance with Mitt now that the likes of Perry have imploded. If Romney does wrap this thing up early, how does he stay in the news for months against an incumbent president, especially since he can’t overtly move toward the center until Tampa?

And what does the photo finish tell us about Iowa?

Santorum won his spot the old-fashioned way, by campaigning his heart out at one Pizza Ranch after another, unmolested by journalists as he made 381 appearances in all 99 counties. Santorum’s success vindicates the shoe-leather rationale for these first-in-the-nation caucuses. Paul, too, spent a vast amount of time in the state.

It’s also apparent that Iowa voters performed their winnowing function. They examined the goods and rejected Perry, Gingrich, and Bachmann to varying degrees.

In the past, candidates have been wary of going too negative and alienating “nice” Iowa voters. But the Citizens United decision changed that. Romney’s PAC pals were able to savage Gingrich with more than $3 million in attack ads because there was no need for the tag “I’m Mitt Romney and I approve this message”—the donors remain anonymous for now as well. Gingrich had plenty of baggage, but the ads knocked him from a lofty perch in just four weeks.

What’s clear after this first contest is that the Republican Party remains deeply divided, and that could be a problem when the Iowa results are long forgotten.