Rick Santorum missed his bullhorn moment.

The surging crowd at Manchester’s Belmont House restaurant was packed so deep that fire marshals ordered half of them evicted, forcing the candidate’s lone advance man to move the event outside. The former senator was mobbed Friday as he made his way through the parking lot, and as a local pol strained to be heard above the din, a loudmouth protester offered his bullhorn, which the man used to great effect.

But Santorum refused the amplification, and as he started to talk about an obscure health-care bill he introduced in Congress 20 years ago, most of the unruly crowd couldn’t hear him, his voice no match for that of the bellowing protester.

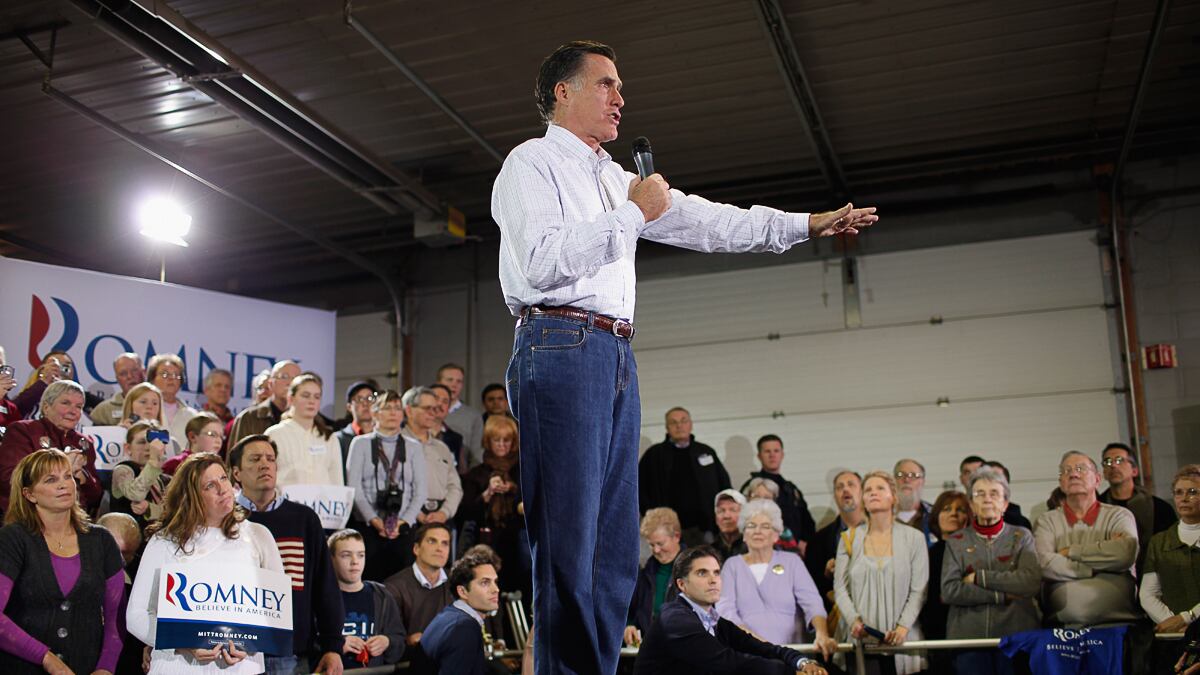

An hour to the north, at the rural Tilton School, Mitt Romney faced his own overflow crowd beneath quietly humming ceiling fans. After a lavish introduction by South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, Romney delivered a well-paced speech punctuated by frequent applause, at one point noting that he had just seen a 1968 yearbook with his father’s picture and “of course it touched my heart.”

The former next-door governor didn’t sound particularly touched, but no matter: he concluded with the picture-perfect scene of handing out spaghetti dinners on a cafeteria line, genially announcing, “Come on through, come on through!” like an exuberant principal. The metronomic precision was broken only when a young woman lingered to tell Romney that taxes should be raised on the rich, before aides hustled her off.

The contrast, days before the New Hampshire primary, was inescapable: One campaign a smoothly functioning machine, the other a ragtag operation scrambling to keep up with an explosion of interest in a onetime also-ran.

But the differences went deeper than that. Santorum is an exceedingly earnest man with the soul of a legislator, lacking the slightest flair for the dramatic. Romney, despite his occasional awkwardness, especially on television, has emerged as a polished performer who is hitting his stride with growing confidence.

Amid the sound-bite warfare and attack ads that define the modern White House campaign, an important truth is often missed: Americans generally gravitate toward the candidate they can imagine coming into their living rooms for four years. That comfort factor helps win elections.

Romney isn’t there yet. He’s still the rich guy with the perfect hair, a governor’s son who had to learn how to chat with voters in a diner. The one discordant note he faced Friday was when a young woman said he was a “multimillionaire with four houses. Would you be willing to give up some of that to help middle-class Americans get tax cuts?” Romney tried to laugh it off, saying he doesn’t own four houses. That’s true, he has three.

Santorum has a rare opportunity in the wake of his virtual tie in Iowa. He won’t win New Hampshire, but the press would trumpet a solid second-place showing, enabling him to consolidate support as the conservative alternative to Romney. A new NBC poll has Romney leading with 42 percent and Santorum in third with 13 percent, behind Ron Paul.

When Santorum emerged in a white shirt and gray sweater-vest to the overflow crowd outside the Manchester restaurant, where many people had sat on the floor awaiting his arrival, there was a sense of excitement that stirs when an underdog breaks out of the pack.

But as Santorum began speaking about limited government and Medicare and capital gains, he delivered his message in a monotone that would have hampered him even if the parking-lot acoustics had been better. His rhetorical appeal to local pride surrounding the first primary failed to produce a raised voice or signature gesture. It was all prose, no poetry.

One might think the grandson of a Pennsylvania coal miner might make more of a visceral connection with a raucous New England crowd, but there was little evidence of that. Even Santorum, who spent the year talking to small groups, seemed taken aback by the wild scene—which included a demonstrator with a boot on his head—at one point likening it to “a Fellini movie.”

Santorum thinks, and reacts, in Beltway terms. When a questioner asked about President Obama’s recess appointment of Richard Cordray to run the new consumer-protection board, Santorum offered a discourse on how this was improper, even unconstitutional, because Congress hadn’t been out of session very long. Only after this procedural detour did he get around to calling the consumer agency “a pretty scary thing.”

Romney doesn’t bury his applause lines. Tieless in a navy blazer, white shirt, and jeans as he surveyed the schoolhouse crowd, he was on the move with a wireless mike, his voice rising to a crescendo as he hit his marks. Obama did nothing to stop a dangerous Iran, not enough to lower unemployment (though the rate dropped to 8.5 percent Friday), swelled the deficit, engaged in crony capitalism, wasted money on solar energy, keeps apologizing for America.

The biggest change from the Romney of 2008, or even of a few months ago, is that he genuinely seems to be enjoying himself. It doesn’t hurt that he’s on the verge of winning the campaign’s first two contests, but there is a verve and a looseness to Romney that has not been seen before. Even when he recites the lyrics to "America the Beautiful," as he regularly does now, the former governor seems unembarrassed by the contrivance.

He can, to be sure, dance around questions with ease. When a woman in the audience said she was struggling with 8.5 percent government-backed loans to put her four children through college, Romney avoided a programmatic answer. Instead, he congratulated her on getting through life as a single mother. He pivoted to the “mind-boggling” failure of education and called for “more competition in higher ed.” But on her complaint about costly loans, Romney simply said “we’ve got to do better” without offering a syllable on how the burden on parents like her might be eased.

The candidate took only a handful of questions and, perhaps mindful that he was at George Romney’s alma mater, briefly sounded amazed that he was running for president. “I saw my dad do it. I never thought I’d follow in his footsteps,” Romney said. “What a thrill it is.” Then he was off to serve spaghetti, dispensing an occasional hug along with the pasta.