When George W. Bush signed No Child Left Behind legislation into law 10 years ago this week, it seemed like the perfect expression of his brand of “compassionate conservatism,” while also redeeming his campaign pledge to use education reform to overcome “the soft bigotry of low expectations.” NCLB passed Congress by overwhelming bipartisan majorities (87 to 10 in the Senate; 381 to 41 in the House) and a beaming Ted Kennedy stood alongside President Bush at the bill-signing ceremony.

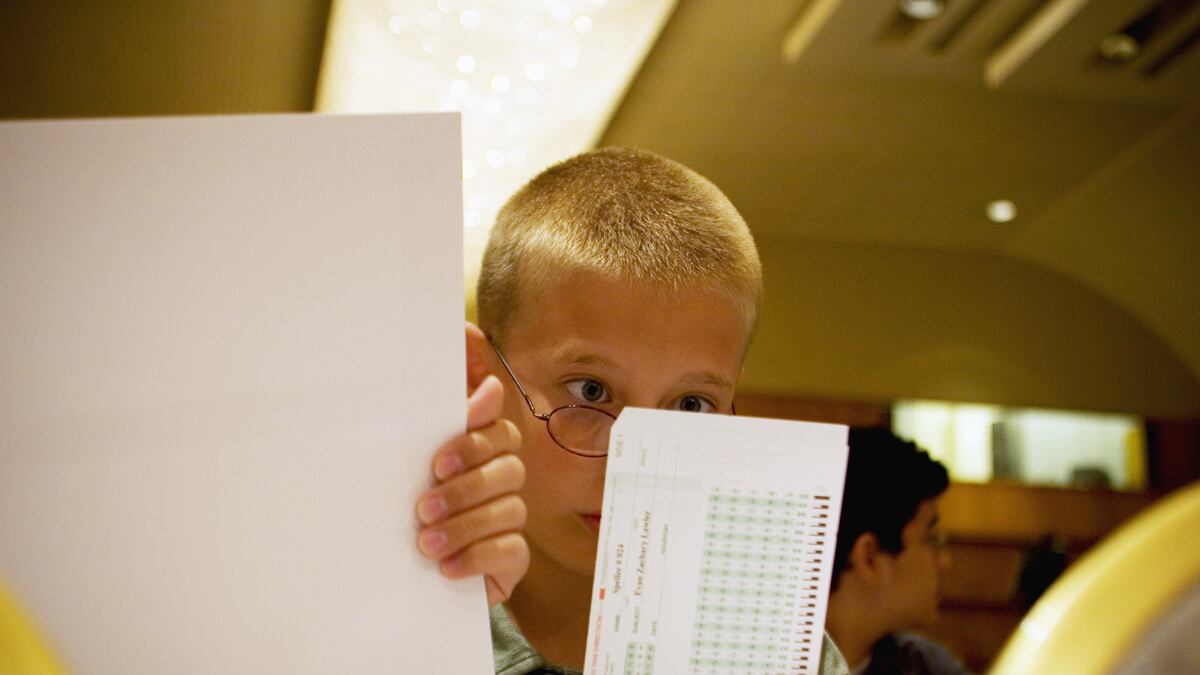

Before NCLB, the federal government had attempted to achieve some degree of educational equity through the Title I compensatory funding program, which sent nearly $200 billion to the nation’s highest-poverty schools over four decades. This massive transfer of funds yielded meager results, however. With the new education law the Bush administration pushed for a results-oriented approach to education reform. The federal government now would require school districts to meet specific goals in return for their Title I funds. The states were required to conduct annual tests in reading and math for all children in grades three through eight, with the results—broken down by race, sex, and socioeconomic status—made public. Narrowing the racial achievement gap framed the measure as a “civil rights” reform that conservatives could easily embrace.

Though well intentioned, NCLB’s perverse incentives left the door wide open to the corruption of educational standards. The law stipulated that all American students must become “proficient” in reading and math by 2014 --- a hopelessly utopian goal – and then set sanctions for those states that didn’t make “adequate yearly progress” in meeting that goal. But the law also allowed each state to determine its own proficiency standard. Since men are not angels, it was inevitable that state and local education authorities would dumb down the tests to make themselves look good to the feds and to the voters.

The framers of NCLB might have avoided this outcome if they had familiarized themselves with the work of the great American social scientist Donald Campbell. According to Campbell, “when test scores become the goal of the teaching process, they both lose their value as indicators of educational status and distort the educational process in undesirable ways.” That’s exactly what seems to have happened.

The best evidence of test-score inflation over the past decade was the growing gap between the number of students that states deemed proficient on their own tests—those administered under the terms of NCLB—and the number deemed proficient by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often referred to as the “nation’s report card.” One reason the NAEP tests are the gold standard in student assessment is that they can’t be gamed by teachers or administrators. Every two years, NAEP math and reading tests are given to a statistically valid sample of all fourth- and eighth-grade students in each state. Teachers aren’t able to teach to the test, and school districts can’t offer students practice tests because no one knows ahead of time which students will be tested.

Most states in the union have reported huge gains on their own tests while their NAEP results haven’t budged. In New York, for example, the percentage of eighth-graders reaching proficiency on the state’s math test rose from 58.8 percent in 2007 to a stunning 80.2 percent in 2009, while the NAEP math scores remained flat over the same span with less than 30 percent of students deemed proficient.

It’s hard to escape the conclusion that states were gaming their tests—not only to satisfy NCLB regulations, but also to celebrate the education miracles that their elected officials have supposedly worked.

One other perverse incentive in NCLB: Because the law emphasized mere “proficiency” and rewarded schools for getting their students to achieve that fairly low standard, teachers and administrators were pressed to boost the test scores of their lowest-performing students but were given no such incentive to improve instruction for the brightest students – the nation’s future engineers and scientists.

A decade after the signing of NCLB, education reformers finally seem to understand the legislation’s conceptual errors and the degree to which it has contributed to a false picture of education progress. Unfortunately, the Obama administration seems determined to double down on the same flawed approach to federal education policy. The administration has offered waivers on the absurd 2014 proficiency goal, but only if the states accept new federal mandates linked to progress on the same unreliable state tests.

“We have to stop lying to children,” Obama’s education secretary, Arne Duncan, announced last year at a meeting of the National Governors Association. “We have to look them in the eye and tell them the truth at every stage of their educational trajectory.” A nice sentiment, but Mr. Duncan concocted the biggest lie of all when he replaced NCLB’s 2014 proficiency goal with the pledge that all American children will be prepared for college-level work by the year 2020.