Next week, art collectors and bibliophiles will have the chance to bid on what’s often called the world’s most expensive book—the last copy to go up for sale, in London two years ago, went for $11.5 million.

But calling John James Audubon’s masterpiece of ornithological art, The Birds of America, a book is to stretch the limits of the term. The four volumes are three feet tall and among them contain 435 massive hand-colored prints. Opening one is a two-person job. Christie’s auction house in New York, where the work goes on sale on Jan. 20, expects this complete first edition to fetch between $7 million and $10 million.

Audubon’s work has always been expensive, in part because of the Frenchman’s exacting production standards. He insisted each bird be life-size, requiring double-elephant folios, the largest paper available at the time. His obsession with detail prompted him to opt for aquatint printing, rather than the cheaper lithography then coming into dominance, and to seek out the best engraver in England, William Home Lizars. In 1838, when Audubon finished his 200-copy run, 14 years after he began, his total cost had reached $115,640, more than $2 million in today’s dollars. He covered it, barely, by selling subscriptions to wealthy collectors. For $1,000, they received several prints at a time, which they could have retroactively bound. Only 120 complete sets are believed to exist today.

The book was a passion project for Audubon. He had drawn and painted birds since he was a boy in France, where he was raised by his father’s wife. (He was the illegitimate son of a French sea captain and his Haitian chambermaid.) He continued in America, where he moved at 18 to avoid Napoleon’s draft. And Audubon continued to paint birds as his business ventures faltered and failed. When his Kentucky trading business finally went under in the panic of 1819, he set out to travel the Mississippi with his watercolors and his gun, shooting birds, posing them, and painting them for eventual printing.

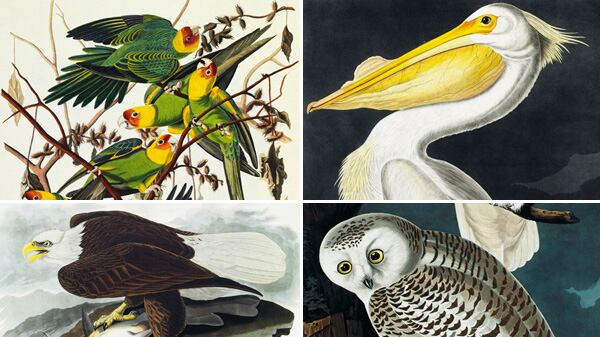

Audubon’s decision to paint his birds in lifelike poses was revolutionary, says Christoph Irmscher, a professor at Indiana University and the author of a book on the artist. Before Audubon, ornithologists depicted birds flatly and schematically. Audubon’s birds fly, swim, and hunt, a dynamism the artist borrowed from French history painting and then brought to the American frontier. A fabulous self-mythologizer, Audubon claimed to have learned his technique from Jacques-Louis David, who was Napoleon’s personal painter.

Audubon posed his birds dramatically, but also accurately. Previously, even though images of birds were flat and used mostly for scientific citation, they would all be the same size, so an eagle would have the same dimensions as a sparrow. Audubon’s insistence on life scale—pinning the stuffed models onto a grid of wires so he could transfer their image to gridded paper at a 1–1 ratio—and his use of aquatint printing, with its nuanced gradations, added to his images’ lifelike physicality. The scale also gave his images their unique compositions: he filled the page with whole flocks of small birds, like the Carolina parakeet (now extinct), while larger ones, like the flamingo, he contorted to fit the page.

“Audubon merged science and art in a very new way, elevating the whole idea of ornithological art,” says Tom Lecky, head of books and manuscripts at Christie’s. “His ambition to do this monumental project has made the book the most valuable in the world and made his name known throughout the world as a great observer of nature.”