Underlying the debate about Mitt Romney and Bain Capital, and whether he and his colleagues were capitalism’s scavenging vultures or its nurturing mother hens, is a larger debate about the nature of wealth in this country. It’s an argument my side has been mostly losing for 30 years, in no small part because of the admitted effectiveness in the media of shallow and shameful remarks like Romney’s quip on the Today show last week that any caviling about either his fortune or Bain’s work constitutes a “bitter politics of envy.” In fact, there is very little envy. But there is a lot of anger. At the heart of what I’m angry about, but also what Mitt’s own father, George Romney, might have been angry about, is the death of what we used to call civic virtue.

Let’s start this way. There are fortunes, and there are fortunes. And there are differences between them, depending on how they’re made. Creators and inventors, nearly everyone would agree, have earned it. Take someone like, say, Paul McCartney. Fine, make your jokes about “Silly Love Songs.” But the fact of the matter is, he has arguably brought more happiness to more of his fellow human beings than any other living person. He’s worth $800 million. Should be five times that, as far as I’m concerned. The drum part on “Dear Prudence” alone (yes, he played the drums on that!) is worth about $40 million. No envy there.

Now take Bill Gates. He invented (or at least popularized and made accessible) technology that revolutionized life. He is worth many, many billions—59 of them, says this website. That’s a little obscene. But hey, he did come up with one of the truly world-historical ideas of our time. Ditto, more or less, Steve Jobs. I put Mike Bloomberg in a somewhat different category. Gates and Jobs changed our lives, all of us, touched the plebeian classes; Bloomberg invented this machine that is used only by the wealth-creating class. But still, it was obviously an invention that many people value.

Athletes and actors? Lots of people think athletes are the most overcompensated of the bunch, but I disagree. Whatever else you want to say about athletes, they are objectively the very best in the world at what they do. Michael Jordan didn’t get to be Michael Jordan because he had a winning smile. There is no Auto-Tune machine for the jump shot. There’s something that’s a little unfair about the endorsements market, but basically, he earned every penny he made with his talent. With regard to actors, it cannot be said as definitively that Leonardo DeCaprio, the highest-paid actor of 2011, is the world’s greatest; but he’s obviously good enough.

By and large, liberals believe that while these people may all as a class be overpaid—a second point, to which we’ll return—they have nevertheless done something creative or inventive to benefit society and/or inspire people. Now we turn to Romney. Private equity isn’t creative or inventive in the way I mean the words above—it’s not writing a beautiful song that moves millions or designing the coolest device humankind has yet known. It’s just about making more money for the investor class—very much including himself.

Sometimes this benefits society, in the form of some jobs, and sometimes it doesn’t. But even when it benefits society, the gains are offset. Is the world better off because Staples and Domino’s, two Bain startups, thrive? No. The world would have just as many paper clips and pizzas if they never existed, more often sold not by mega-chains but by the kinds of mom-and-pop stores the chains drove out of business. And for this—and for stripping companies, loading them up with debt, and sending them out into the world, sometimes to make it and sometimes to fail—Romney nets a quarter-billion dollars? He did not put that much into society, and he should not be getting that much out of it.

Even still, I am not envious. Believe me, I wouldn’t want a quarter-billion dollars ($10 million would be plenty, thank you). Romney’s fortune is, however, mystifying and kind of maddening to millions of us. But it’s not even about him per se; rather, it’s about how haywire the high-end economy in this country has gone since the 1980s. And this is my second point: to the extent that people are angry about high-end salaries, it’s because those salaries have exploded beyond all reason and proportion. Everyone knows that CEOs who used to make 12 times the average worker’s salary now make 300 times, or whatever it is. Defenders of this try to say the job is much more complex in a global age. But it’s not just CEOs. It’s everyone mentioned above (musicians, athletes, etc.), along with white-shoe law-firm partners, university presidents, television news anchors, and so on. It’s insane. And, as we so often see, the compensation is only haphazardly tied to job performance. Walter Cronkite, who almost always led the ratings, never made more than $1 million a year (he retired in 1981; that would be $2.6 million in adjusted dollars). Katie Couric, who rarely if ever led the ratings, made $15 million a year.

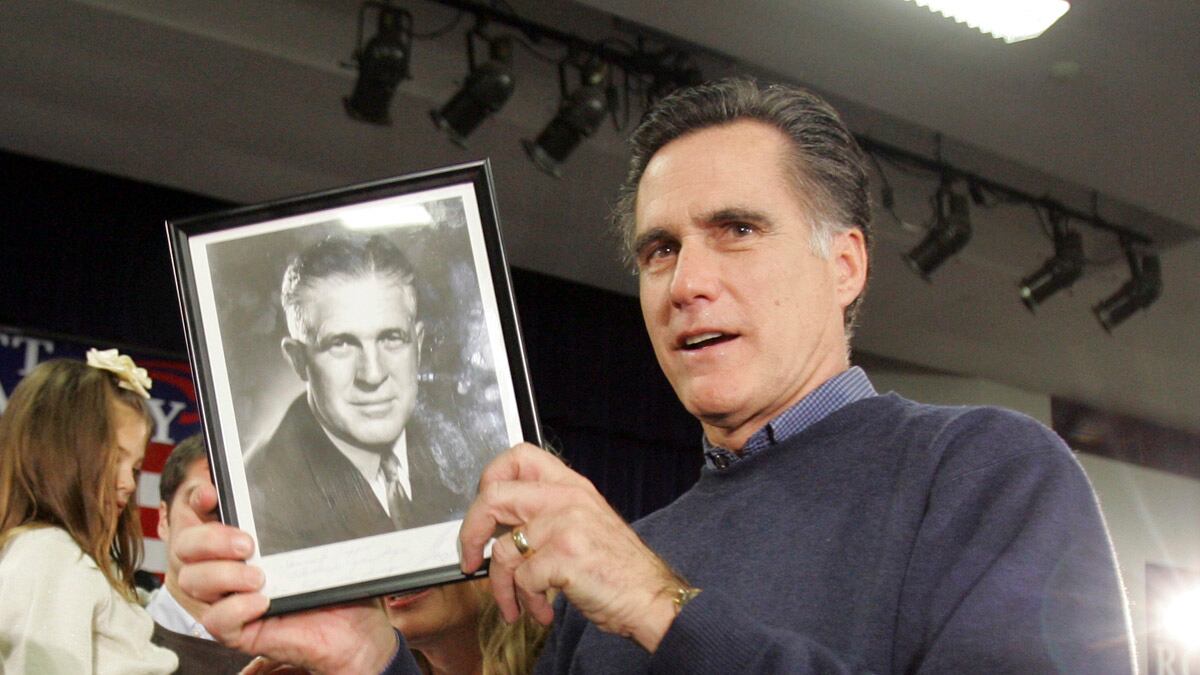

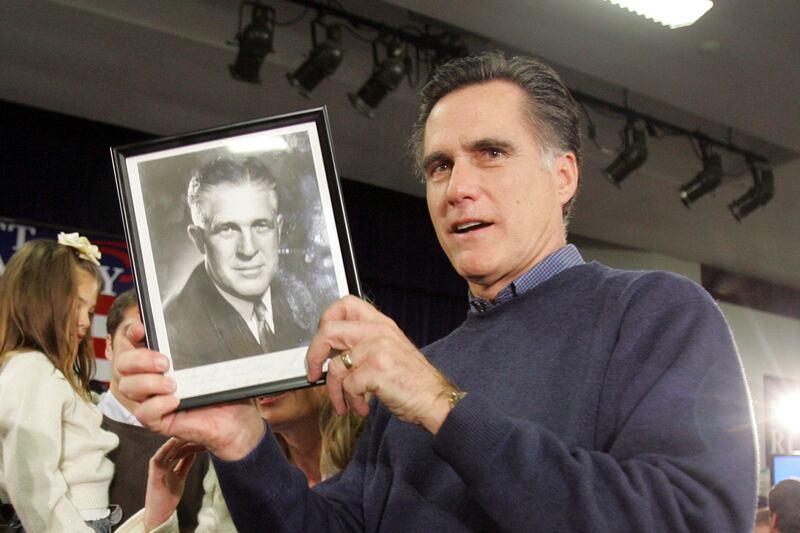

What check is there to keep these numbers from just spiraling upward forever? Probably nothing. But there used to be something that did. It was called civic responsibility, or civic virtue. Or plain decency. We once had a collective sense in this country that TV news anchors simply didn’t need to make $15 million a year. Interestingly enough, a former famous and very successful American CEO, back in 1960, refused a bonus of $100,000, saying that no executive needed to make more than $225,000 ($1.4 million today), his salary at the time. That was George Romney, whose son Mitt was 13 at the time and who one might have hoped was listening.

Romney (Mitt, not George) is appallingly wrong about “envy.” In assuming envy, he assumes that everyone wants to get rich but isn’t “good” enough. That’s a risible insult to the teachers and social workers—or, if you prefer, the priests and farmers—who do what they do out of passion. It’s no wonder he can’t connect with these people. We may not be able to solve the civic-decency problem, but we can solve the problem of the apple that evidently fell rather far from the tree.