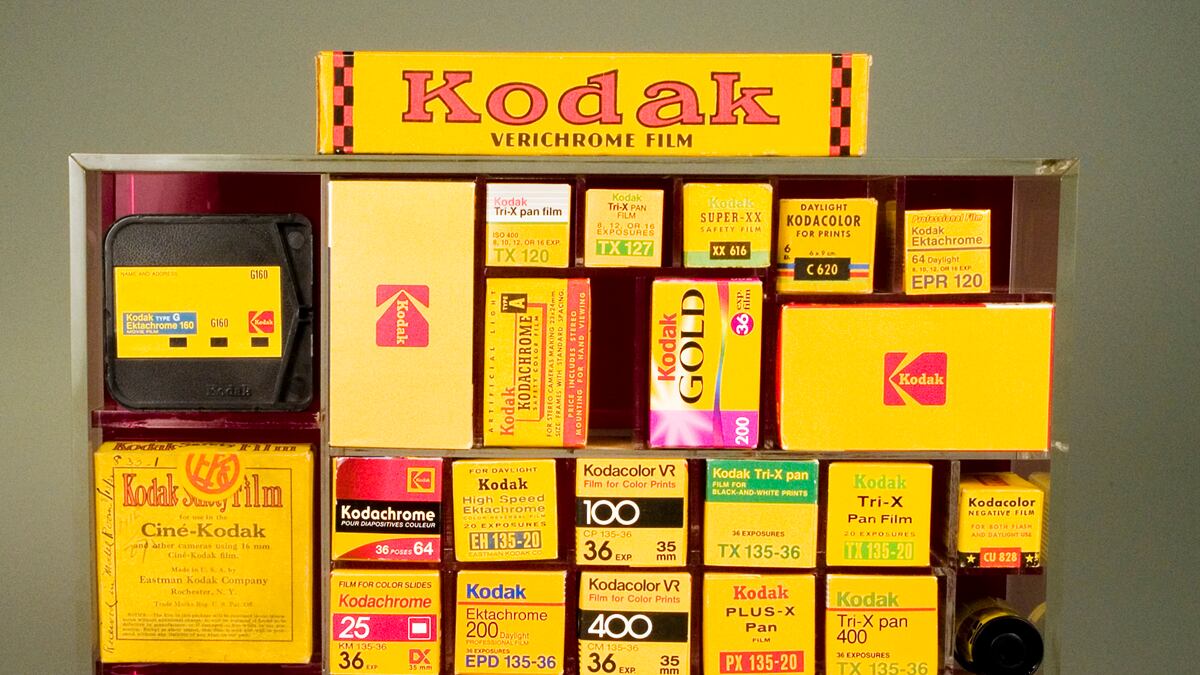

Stack upon stack of yellow boxes, in all sizes and shapes, with the single word Kodak spelled on each one in red—in photo stores across the country, these didn’t stand for just another brand of film, or enlarging paper, or developer. For generations of hobbyists and pros, camera hacks and artistes, those two colors stood for photography.

With yesterday’s announcement that Kodak has gone bankrupt, that image may have faded for good. “They were known as the Great Yellow Father,” says George Tice, a dean of American photography and a famous darkroom magician. And now Dad is, if not dead, at least in the ICU, and his old friends can do nothing but think back, and worry.

Tice has built his art around Kodak supplies, he says, and of late he’s been watching them slowly thin out. “I’ve been using Kodak Tri-X all my life—and you used to be able to buy 8 by 10 [inch] Tri-X in 50-sheet packages, and now you can only get it in 10 sheets.” The Kodak selenium he tones his prints with used to come by the gallon, “and now I have to buy four quarts, and pay twice as much.”

At least he still has the Kodak darkroom funnel he got when he was 14, which was 59 years ago. The bankruptcy “is a sad day,” he says. “But the saddest day was when they first stopped making [black-and-white] paper.”—That was in 2005—“Then I knew this day was coming…. You’d like to know that products you use would be around. But now you don’t know. So do you stock up on things, and get a few years’ supply? You don’t know.”

Kodak insists that the bankruptcy doesn’t change anything. (Yet.) Spokesman Chris Veronda says that although Kodak’s traditional business has been declining “at high double digits” since 2003, thanks to some massive cuts in spending (13 factories and 130 labs shuttered; 47,000 layoffs) Kodak’s analog production has now become “sustainable and profitable.”

That doesn’t make it less painful for photo buffs to hear the words “Kodak” and “bankruptcy” in the same sentence. “You’re really coming to the end of an era,” says Yossi Milo, a prominent New York photography dealer. In 10 or 15 years, the analog techniques of the Great Yellow Father may seem “something completely historical,” he says. And there will be a real loss when that happens. “There’s something so magical about traditional prints,” Milo says, and mentions how several of his younger photographers still seek out that magic.

Mike Brodie, a 26-year-old who is one of Milo’s newest finds, shot teenage train-hoppers on 35mm color Kodak film, and then hunted down a frozen supply of old Kodak paper for the photos to be printed on. “It still has this beautiful vibrancy. And once this paper is gone, that’s gone,” says Milo.

Jim Megargee, the 65-year-old cofounder of MV labs in New York, was once Annie Leibovitz’s personal printer—in the days before she’d gone digital. Now he runs one of the country’s few all-analog labs, in business for almost two decades. He’s not surprised at the bankruptcy news. “This has been coming for a long time—you could see them nibbling away at the edges,” he says, noting that he’s watched many of his favorite Kodak supplies gradually disappear from the lineup. “We’ve been advising our clients not to get too attached to Kodak materials. I’m hard-pressed to say, ‘Maybe you should use Tri-X.’ Maybe in two or three years, there won’t be any more Tri-X.”

He can imagine Kodak’s most storied black-and-white film going the way of Kodachrome, its most famous color stock, which ceased production in 2009. “Everything’s up in the air, and we’re waiting to see what happens. We’re waiting to either put the one shoe back on, or for the other one to drop.” Megargee knows that, one way or another, someone, somewhere, will always meet the boutique demand for analog photographic supplies—just as there are suppliers to be found if you want to do daguerreotypes or wet collodion work. He worries, however, that some current analog mavens may be so deeply dedicated to particular Kodak materials that if those disappear, they might throw up their hands and make the jump all the way to digital.

That’s what Marilyn Minter has done. Although her images are as hip and contemporary as anything could be, she’s been known as a hold-out for old fashioned film and paper. But—you read it here first—she has just now switched over to digital. Hunting for analog supplies and technicians has been getting to be more of a pain by the day, she says, and she no longer sees the quality gap she once did between silver emulsions and bytes.

“Digital is starting to match analog in terms of detail. … Digital is catching up—I never thought I’d say that.”