The Last Holiday: A MemoirBy Gil Scott-HeronGil Scott-Heron’s death in May 2011 reminded us that hip-hop, a commerce machine today, once found at its center a devotion to righting social wrongs through the force of simple words.

The musician and poet did not care for the label “godfather of hip-hop,” despite having released the still-powerful “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” But he should have found no shame in influencing second-generation rappers, like Chuck D, with his uncompromising political tongue. With this posthumous memoir, Scott-Heron—who throughout his career not only released 20 albums but also two novels and three collections of poems—can at last be recognized as a top-notch writer. The Last Holiday is one of the most unpretentiously aware autobiographies by a musician. Here are the opening sentences: “I always doubt detailed recollections authors write about their childhoods. Maybe I am jealous that they retain such clarity of their long agos while my own past seems only long gone.” Everything you need to know about his legacy is there, from the doubt against authority figures and his gentle self-deprecation to the cognizance that he attributed to others while it was he himself who actually possessed the clarity of conviction. The motivation for this chronologically loose but thematically tight book was to give Stevie Wonder the recognition he deserves when he pushed for a national Martin Luther King Jr. Day, in a 1981 tour. Even in these final words, Scott-Heron denounced an “all eyez on me” attitude and chose to be a social observer. A class act.

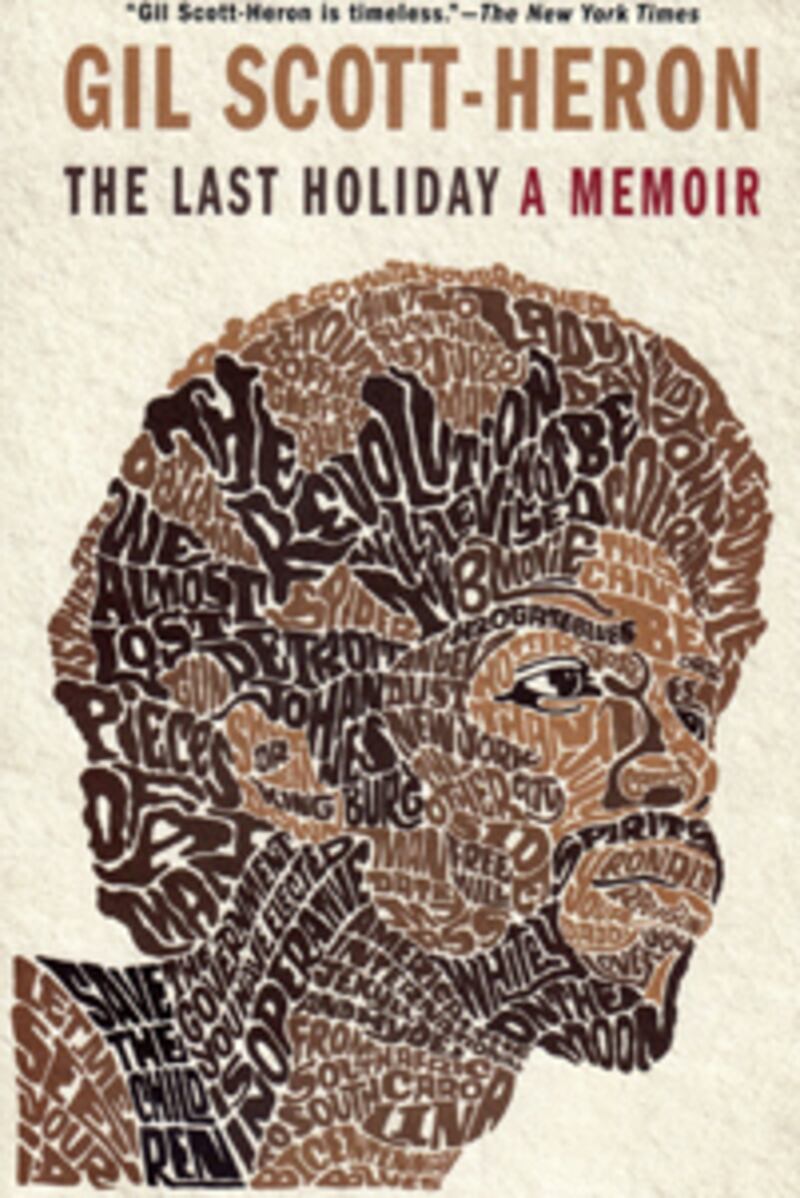

The Last NudeBy Ellis AveryA dashing, brash painter begins an affair with her beautifully innocent model in 1927 Paris.

There’s a rich tradition of fictionalized artist biographies—consider The Agony and the Ecstasy, Moon and Sixpence and Girl With a Pearl Earring. The appeal is to be allowed into the absurdly exclusive inner circle of enigmatic figures prone to uninviting you if you so much as look at them the wrong way. The Last Nude takes a gamble. Instead of choosing as a subject one of the blockbuster masters like Michelangelo or Vermeer—which would have guaranteed great sales—Avery imagines the life of Tamara de Lempicka. Who? You might not be familiar with her name, but you’ve seen her jazz-age nudes. The advantage of relative obscurity (I wouldn’t call her a particularly “important” figure) affords Avery the chance to project on her subject a flexible, elastic style, whereas the masters wouldn’t let anyone mess with them. De Lempicka, as a character and as an artist, carries the metallic, American sheen of art deco, the angular hostility of the Italian futurists and the French and Spanish cubists, and the expressive decadence of the German Neue Sachlichkeit. All of which is to say that her story stands as something like a portrait of the splintering West—the shattered idea of the West—at a pivotal time. “Her English was like sandpaper, Slavic and pained,” the 17-year-old narrator Rafaela, who’s also de Lempicka’s model and muse, says. That’s a marvelous line, and I wish there were more like it.

Joseph Roth: A Life in Letters.Translated and edited by Michael HofmannThe poet Michael Hofmann has compiled and translated the letters of Joseph Roth, and they heap into a dense, dark portrait of a remarkable life.

“One must bury the old world, but one must give it a decent burial,” says the narrator of the story “The Bust of the Emperor.” Its author Joseph Roth, who was born in 1894, dedicated his life to just that proper memorial for his beloved Austro-Hungarian empire, in novels (The Radetzky March most famously) that rival the brilliance of Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann, and Robert Musil. Roth’s inner life was overwhelming, and the letters with his fellow Austrian writer Stefan Zweig are particularly devastating, as Roth begs endlessly to his friend to save him from the bottle and the crumbling world around them: "I want to live, but I can't go on. I am getting sicker, and I have no one. My loneliness is such that I will cling to anyone at all, so as not to sleep, or rather not to lie in bed, not sleeping." The letter reminds one of Max Demant, an Army surgeon in The Radetzky March, who is enslaved by military rules and must accept a duel in the name of honor, and resigns to the fact by drinking and drifting into a half-sleep that's not unlike death. He goes to the duel and is killed. Roth himself died in 1939, four days after collapsing from hearing the news that his friend, the playwright Ernst Toller, hanged himself in New York. Three years later, Zweig died in Brazil in a double suicide with his wife.

The World We Found By Thrity Umrigar The author of the hit novel The Space Between Us gives us something like The Big Chill for 40-something Indian-Americans.

The immensely popular novel The Space Between Us became successful on the strength of Thrity Umrigar’s commitment to everyday English while dramatizing India’s exotic terrain. The Indian-American novelist hasn’t changed her approach much, and with The World We Found, she serves up the reunion of four women who were university friends in late 1970s Bombay. The reunion genre sells sentimentality and nostalgia by the bucketful, but it takes an author unafraid of revealing herself to pull it off. There are times when you wish this finely crafted book would be less careful and take more risks and provide more comedy, but it's hard to fault a writer for not living up to the great sentimentality of Dickens.

Perlmann’s Silence By Pascal Mercier Mercier this time paints a portrait of a man covering his tracks as he gets increasingly mired in academic games and psychological purgatory—they’re pretty much the same thing.

Mercier’s U.S. debut, the exceptionally successful Night Train to Lisbon, dealt with a stale Swiss high-school teacher who becomes undone when he pursues the story of a persecuted Portuguese poet—it was literary and haunting, recalling Name of the Rose, Steppenwolf, or The Magus. In his fourth novel—but only the second to be translated into English—he again ruins the life of someone: Philipp Perlmann, a widowed linguistics professor who tries to plagiarize the paper of his colleague Leskov. (Mercier is himself a philosophy professor in Switzerland.) Guilt has a similar force here as in Patricia Highsmith, Vladimir Nabokov, or even Henry James’s The Golden Bowl. But what a translation of Mercier lacks is the vanity of style that those masters conjure up. He doesn’t deal in pretty language, but his advantage lies in his “everystyle,” like Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Leskov is, in fact, Russian, and stalks the novel like a conscience you have to worry about.