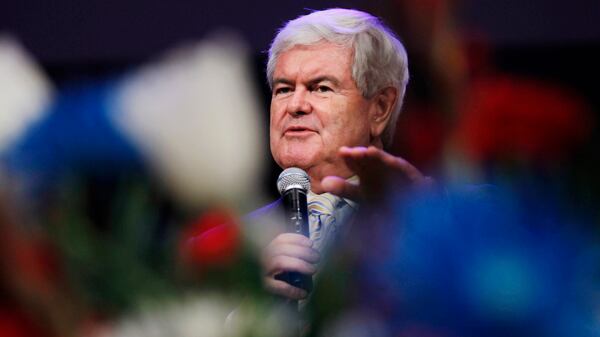

Are the media about to bury Newt Gingrich for the third time, shoveling extra dirt on his campaign casket to just to make sure?

That’s a distinct possibility if Gingrich loses Tuesday in Florida.

A little over a week ago, Gingrich looked like a serious threat to capture the Republican nomination. He had just won a smashing victory in South Carolina, he was dominating the debates, and he had shot into the lead in the Florida polls while Mitt Romney was getting tangled in his taxes.

If Gingrich could somehow pull out a win in Florida, it would be devastating to Romney, who would be in the position of having lost three out of the first four contests. But that seems unlikely at this point, and Newt is looking more like a one-hit wonder.

Be wary of all prognostications, of course. The media’s track record in this 2012 campaign has been nothing short of embarrassing.

The press wrote off Gingrich for the first time last summer, when most of his staff quit after he took Callista on a cruise and generally failed to follow their advice. Yet somehow, by December, the former House speaker had surged into the lead in Iowa.

Gingrich collapsed under a barrage of negative ads from a pro-Romney group, and that led to the second round of political obituaries. The pundits never seem to learn. Then Gingrich tore up the script by pulling off a double-digit victory in South Carolina, which usually serves as a bulwark for establishment candidates against insurgent challengers.

Has Newt now run out of resurrections?

Suddenly, Gingrich found himself under fierce assault in the Sunshine State from what remains of the GOP establishment. Party war horses such as Bob Dole surfaced to denounce Newt as a wild-eyed head case who would ensure Barack Obama’s reelection. The conservative media, led by the National Review, Matt Drudge, and Ann Coulter, trashed him in an obviously orchestrated assault. This wasn’t the handiwork of the liberal press, it was a vast right-wing conspiracy—and all the more devastating coming from those who should be his ideological allies.

At the same time, Gingrich lost his footing in trying to make the transition from protest candidate to plausible nominee. When I watched him campaign in Florida, he seemed flat, sticking to his stump speech and allowing himself only brief jabs at Romney. He was also undisciplined at times, wandering off into digressions about the U.S. buying aircraft from Brazil that left his audience puzzled.

And then there were his underwhelming performances in the two Florida debates, in the forum that was supposedly his greatest strength. Romney clearly walloped him in the CNN debate, portraying Gingrich as a failed leader forced to resign from the House who later cashed in as a Beltway insider. Gingrich seemed unprepared, especially when he accused of Romney of having holdings in Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and Mitt parried by saying that Newt did as well. What’s more, Gingrich’s patented denunciation of the media, which had worked so well against John King, boomeranged when Wolf Blitzer fought back, saying he was merely quoting Newt’s own inflammatory words against Romney.

Gingrich was left to sputter to The Washington Post that Romney had turned in “the most blatantly dishonest performance by a presidential candidate I’ve ever seen”—so dishonest, said Gingrich’s spokesman, that his man was stunned into silence.

To make matters worse, Romney and his super PAC greatly outspent the Gingrich side on television ads in a state with costly media markets.

One Gingrich blunder may resonate beyond the complicated back-and-forth about investments and lobbying rules. In campaigning near Florida’s NASA facilities, Gingrich revived his idea of building a base on the moon. While he may view such a call in JFK-like terms, it reinforced the notion of Newt as a space cadet.

If Gingrich loses the Florida primary, he faces a rough February. There are caucuses in Nevada, Maine, Colorado, and Minnesota, and working a caucus requires the kind of well-organized and well-financed campaign that Romney has and Newt does not. There are also primaries in Missouri (where Gingrich failed to make the ballot), Arizona, and Michigan (a Romney stronghold where his father was governor and an auto industry executive).

Oh, and no more debates until Feb. 22.

Gingrich vowed on Saturday to campaign all the way to the convention. He has shown an uncanny knack in this campaign for defying political gravity and confounding the oddsmakers. He can obviously stick around and cause Romney more damage, hoping for another comeback when 10 states vote on Super Tuesday, March 6. But if Romney continues to methodically pile up delegates, at some point the math becomes impossible to deny.