In the Land Where Time Disappears

It’s 2013. America is ruined after a second financial crisis, which caused the dollar to lose one third of its value in the course of a day and the price of gold to skyrocket. China’s economy—guided by leaders employing a mix of communism and state capitalism—emerges as the triumphant global hegemon. Chinese conglomerates gobble up American firms, including Starbucks. The Communist Party presides calmly over a nation of deliriously happy citizens. The problem is, no one in China can seem to remember the tragic month of February 2011, when the chaos all began …

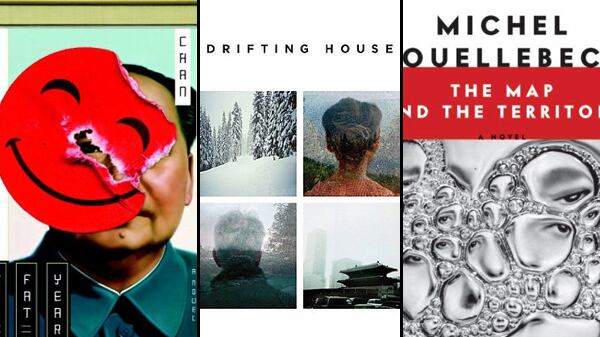

Thus runs the premise of The Fat Years, a novel that sent shock waves through the Chinese blogosphere when it was first published online in 2009, and which was released recently in the United States.

The novel’s protagonist, Old Chen—a Taiwanese writer living in Beijing and struggling with the myopia of mainlanders—is based on the author himself, a shy media mogul and cultural commentator named Chan Koonchung. In an interview in a Starbucks last fall, Chan told The Daily Beast that he was surprised his book received so much mainland attention—it spread like wildfire over email and was smuggled across the border in print form from Hong Kong. The country’s rightists (the rough ideological equivalent to America’s Democrats) praised it for describing the “counterfeit paradise” of modern China, while leftists appreciated the notion of a strong China taking its place as first among equals. “The liberals probably see it as a criticism, and the anti-liberals see it as a vindication,” says Chan.

Like all dystopians, Chan sees the responsibility for mass delusion in China falling not only on the party but also on the people themselves. His protagonists kidnap a high-ranking government official who explains to them the secret of the missing month: As the second American financial crisis began, protests erupted around China. Normally the Chinese government would crack down on protests immediately; this time it didn’t respond. Days passed. The looting and violence escalated and the country slowly slipped into chaos—the prevention of which sits at the heart of the Communist Party’s claims for existence. “The machine of the state was waiting for the people of the entire nation once again to voluntarily and wholeheartedly give themselves into the care of the Leviathan,” says the official. The Army entered; the people welcomed them—and the ensuing violence—with open arms. After ruthlessly crushing dissent and restoring order, the government added a derivative of the drug ecstasy to the water supply to make people happier. But the leaders don’t go so far as forcing people to forget that February—the Chinese nation decides to abandon the month itself.

“Most people see it as a metaphor for things forgotten by people,” says Chan—events like China’s great famine in the 1950s and '60s that killed tens of millions of people, or the 1989 massacre in Tiananmen Square where tanks crushed the pro-democracy movement. Neither historical event is usually mentioned in public or in private. “As a nation, people forgot about their past. They have a very selective memory of the past so they can survive the present. Otherwise it would be too painful.”

China’s state-run media praised The Fat Years when it came out, though it emphasized Hong Kong–raised Chan’s outsider status and managed to ignore the parts about amnesia and mass killings. An article republished in the party’s official mouthpiece, The People’s Daily, praised the novel’s protagonist for understanding Chinese culture; another article thought the citizens in The Fat Years were much better off than those in George Orwell’s dystopian 1984 world of Oceania. Still, some readers seem to get the metaphor: a talk at a popular lecture series featuring Chan bore the title “Nothing Happened: What Really Happened?” “The author sees things with clarity,” says Xu Zhiyuan, an influential young Chinese essayist.

China's economy grew at 9.6 percent in the first half of 2011; throughout that year the government arrested hundreds of lawyers, intellectuals and journalists, many of whom were tortured. Many of the targets think the campaign is tied to the upcoming party transition in 2012. At the same time, China’s middle class is reexamining its social contract with the party. “That’s why people say, ‘Your book is coming true,’” Chan says. “The party is saying, ‘When we are in crisis, we could crack down again. So don’t be too comfortable.’”

—Isaac Stone Fish

The Personal Is Political

Krys Lee moved back. Though her family immigrated to the United States when she was young, and she was educated in both America and England, Lee returned to South Korea as an adult. Today she edits, translates, and teaches in Seoul, while also working underground in support of defectors from North Korea. But Lee describes herself as an “outside-insider” in Korea because of her time in the West, just as she feels a half-step removed from American culture. She considers herself as living in “a kind of drifting house that becomes a home wherever I happen to live.” It’s a metaphor that drives her first book. Drifting House is a collection of stories that reviewers compare to the work of Katherine Anne Porter, Carson McCullers, and Jhumpa Lahiri.

It is only coincidence that Drifting House debuts in the immediate wake of the death of Kim Jong-il. North Korea is transitioning to the rule of Kim Jong-un, and national mourning appears to be in part coerced. With Lee’s uncommon vantage point on life in both Koreas and in the West, Drifting House offers a rare look at how damaging politics takes a personal turn, undermining even what we are able to call home.

“A Temporary Marriage” follows Mrs. Shin to a marriage of convenience in America, where she searches for the daughter taken by her ex-husband. “At the Edge of the World” features a precocious 10-year-old in a family of North Korean refugees who discovers his father weeping before the shaman next door. An artist in “A Separate Sorrow” struggles with the tension between what she wants and how she wants others to see her. In the title story, three haunted children try to escape famine in North Korea by traveling through the snowy mountains in search of the Chinese border. And in what may be my favorite story, “The Goose Father,” Gilho is a middle-aged accountant in Seoul who takes in a new and strange tenant: a young man who brings with him a goose that he believes to be a new incarnation of his dead mother. His arrival ignites a series of painful awakenings for Gilho, who has sent his family off to America, and who once was a poet.

This is a dark book. The greatest strength of these nine stories is Lee’s ability to locate them in the strange and brutal dimensions of lives distorted by dictatorship, exile, expatriation, and even hunger. Her stories also slide through the quiet violence of divorce, loneliness, parenthood, and erotic attraction. Ingrained sexism suffocates the ability of many characters to move through their cities and their homes as whole people. Korean veterans who fought for the American Army in Vietnam are found neglected and amputated. Unemployment and withheld pensions unsteady South Korea after the 1997 financial crisis. Within the first four pages of “The Salaryman,” the title character learns that his job “no longer exists.” He retreats to Yeoido Park, where other men in suits sit on benches and read newspapers. They will spend each day here, and each day go home to tell their families that, yes, work was fine, “until there’s no money left in the bank account.” Later the salaryman is among the depleted poor who congregate in Seoul Station, left to beg and ferociously defend what is thrown his way. “The green bills separate you from who you were the day before, and you want to live because you are a human being and you deserve it.”

Lee is a patient storyteller with a distanced, mostly omniscient point of view. Such a sweeping, plain-style narration is essential for lacing together a collection that unfolds in three countries. The even tone lifts these stories out of melodrama and turns them instead into pristine things that are as unsparing as they are compassionate.

Lee’s images also sometimes grate awkwardly against each other. In “A Temporary Marriage,” Mrs. Shin has just arrived in the U.S., and she has met Mr. Rhee, the man with whom she has arranged an on-paper marriage. “’You have such young skin,’ he said, admiring her smooth, round face, her eyes the shape of plumped kidney beans … She was tired and frightened, so her words clicked like stilettos on tile.” The similes read like non sequiturs.

But Lee makes up for it elsewhere when her eye for detail finds images that are unnervingly accurate. In the same story, Mrs. Shin has violent erotic dreams. “She woke up trembling with excitement, her arms filmy with sweat and the residual scent of sex … Downstairs she sat and sipped from a glass of water only after she spread a handkerchief on the sofa.”

That handkerchief reveals the precision that is Lee at her best.

Humor brightens the bleak pages of Drifting House. Often this comes in the voices of adolescents. Indeed, children and childlike adults are the truthtellers in these stories. Weighted with tragedy, but not yet broken, young people try to cultivate peace for adults who are sinking from a loss of hope. These children reveal another way of being in harsh circumstances—that is, an honest way of being that saves them from despair, if not sorrow. It is their bravery that lingers past the final pages.

—Anna Clark

Enter the Author

“Michel Houellebecq” seems like he’d be an interesting person to know. “Houellebecq,” who plays a central role in Michel Houellebecq’s latest novel, The Map and the Territory, is for the most part a fictional doppelganger of his nonfiction self. But aspects of the author’s well-known persona as the enfant terrible of French letters have been tempered a bit—just enough, in fact, to make him a charming figure and to set this book apart as something less nihilistic and cynical than the rest of his oeuvre. This novel, his fifth, won the 2010 Prix Goncourt, France’s highest literary honor, and its relatable themes of lost love, the indignity of aging, and the absurdity of life (this is a Houellebecq novel, after all) seem geared to reach a wide readership—an aim that appeared absent in the past, even as some of his works became overseas bestsellers.

In a stark departure from his previous books, The Map and the Territory has a clear narrative progress, rife with drama, change, conflict, and insight. If it’s not an overly sunny tract that makes you want to listen to the Carpenters (thank God), it’s absent the sex obsession, casual racism, and smutty provocation that many critics found in loathsome evidence in earlier works.

The protagonist is an artist named Jed Martin, “a pretty boy, but of a small and slim kind not generally sought out by women.” Jed’s father is an architect who has made a successful, if unfulfilling, career as the designer of high-end resorts; his mother committed suicide right before Jed’s seventh birthday, the cause never discussed by his father, “a dry, serious man” who “was the head of a broken family and had no plans to mend it.”

Jed, like his father, doesn’t put much stock in human relationships. He’s not misanthropic; he’s largely indifferent. In high school he didn’t have a single close friend, and this wasn’t a source of angst. “Instead, he spent afternoons in the library, and at the age of eighteen, having passed the baccalaureate, he had an extensive knowledge, unusual among the people of his generation, of the literary heritage of mankind.”

Drawing had been his first devotion, but he shifts to photography when he enters the Beaux-Arts de Paris. He’s not interested in photographing people or landscapes. Rather he embarks on “the systematic photography of the world’s objects … Suspension files, handguns, diaries, printer cartridges, forks: nothing escaped his encyclopedic ambition, which was to constitute an exhaustive catalogue of the objects of human manufacturing in the Industrial Age.”

His photographs of Michelin maps represent the next big step in his evolution as an artist. At his exhibition, “Jed had displayed a satellite photo taken around the mountain of Guebwiller next to an enlargement of a Michelin Departments map of the same zone. The contrast was striking: while the photograph showed only a soup of more or less uniform green sprinkled with vague blue spots, the map developed a fascinating maze of departmental and scenic roads, viewpoints, forests, lakes, and cols. Above the two enlargements, in black capital letters, was the title of the exhibition: THE MAP IS MORE INTERESTING THAN THE TERRITORY.”

These works bring Jed to the attention of Olga, a Russian beauty who works for Michelin and becomes his girlfriend. The photographs are critically acclaimed (because art critics are fools; that seems the obvious authorial message), and with the help of Olga and Michelin, the works become huge sellers. She and Jed settle into a happy routine, often enjoying weekend jaunts to Michelin-rated restaurants. “It was already … the preparation for that epicurean, peaceful, refined but unsnobbish happiness that Western society offered the representatives of its middle-to-upper classes in middle age.”

When Olga is offered a huge promotion back in Russia, she invites Jed to come with her.

“She was young, or more precisely she was still young, she still imagined that life offered various possibilities, that a human relationship could go through successive and contradictory developments.”

Jed feels otherwise. He lets her slide out of his life, too blasé to care. A cycle has now completed itself, he feels. He turns his attention to art, focusing now on painting. Over the next seven years he paints “The Series of Simple Professions,” representing men and women in various occupations. His explanation for the project is—like his reason for taking photographs of industrial objects—exceedingly trite.

“What’s defines a man? What’s the first question you ask a man, when you want to find out about him? In some societies, you ask him if he’s married, if he has children; in our society, we ask first what his profession is. It’s his place in the productive process, and not his status as a reproducer, that above all defines Western man.”

And yet the paintings become extremely valuable—so much so that at least one person is killed for one. This is again an obvious sendup of the art world, where people often place value on objects of questionable worth. When Jed is putting together a catalog of this project, his gallerist, Franz, suggests that he hire “Houellebecq” to write the accompanying text. Jed travels to Ireland to meet the writer, and their interactions—here and later—are the most enjoyable parts of the book, as Houellebecq the author takes great fun playing with his public persona.

Jed says, “On meeting you, I expected something … well, let’s say, more difficult. You have the reputation for being very depressed. I thought, for example, that you drank much more,” to which “Houellebecq” replies, “You know, it’s the journalists who’ve given me the reputation for being a drunk; what’s curious is that none of them ever realized that if I was drinking a lot in their presence, it was simply in order to put up with them.”

Jed likes the writer, but he doubts they can become friends.

“Jed didn’t think he was capable of such a feeling: he had gone through childhood and the start of adolescence without falling prey to strong friendships, while these periods of life are considered particularly propitious for their birth. It was scarcely probable that friendship would come to him now, late in life.”

Jed’s not sad or depressed. He’s simply unattached. Even when Olga reappears in his life, he doesn’t see it as an opportunity to make up for possible past mistakes. He’d rather be alone.

“He sometimes had the supermarket all to himself—which seemed to him to be quite a good approximation of happiness.”

“Houellebecq” and Houellebecq would likely concur.

The last third of the novel is largely a police procedural surrounding the aforementioned murder. A satire of the art world evolves into a classic whodunit, the author’s choice of a murder victim both shocking and yet quintessential Houellebecq.

—Cameron Martin