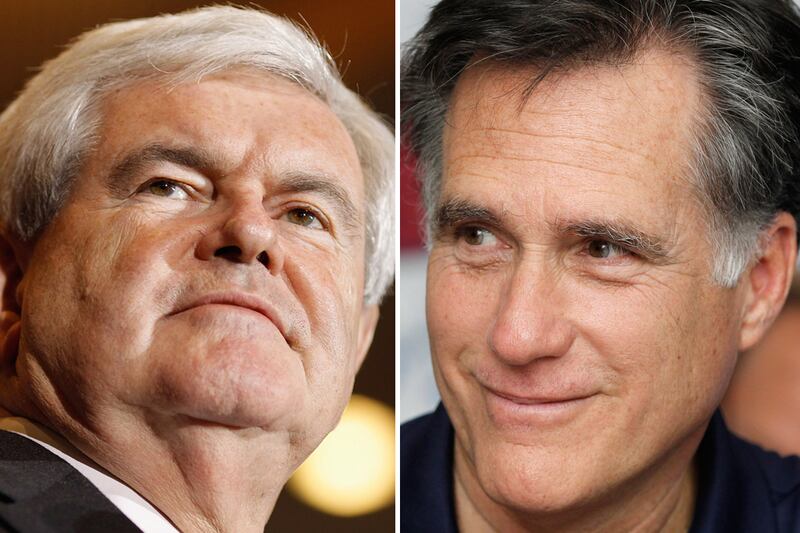

The bruising battle in Florida didn’t turn nasty because the philosophical differences between Mitt and Newt were so significant; it got ugly because the disagreements between them were so trivial.

What could the two contestants argue about when they took largely identical positions on all the great issues of the day?

Unable to exploit or explore clear distinctions on economic, fiscal, social, or national security concerns, they were left to squabble about personal stuff—assaulting one another’s integrity, sanity, consistency, tax returns, business history, political mistakes, associations, and fundamental worth as human beings. Instead of debating who has presented the best plans for tax reform, spending cuts, or curbing the Iranian bomb, they spent the last week before a crucial primary election discussing Newt’s alleged exaggeration of his role in the Reagan Revolution or Mitt’s purportedly nefarious plot to force Holocaust survivors to consume non-kosher food.

It’s easy to see why the two men might come to resent and despise one another. Gingrich has worked for 40 years to organize and inspire conservative Republicans in their push for political power, and now he sees his path to the nomination suddenly blocked by a spoiled, preppy multimillionaire who spent most of that time disengaged from electoral activism and describing himself as “moderate” and “independent.”

As for Romney, he built a beautiful, stable family while toiling tirelessly in the private sector to compile a sterling record remarkably free of scandal of any kind, only to find the nomination he knows he deserves awkwardly threatened by a shopworn, overweight gas bag whose entire life has been punctuated by embarrassments, accusations, and explosive unpredictability in the personal, political, and even business spheres.

Romney now claims to care deeply about the conservative cause but Gingrich wonders why he never involved himself in the nuts-and-bolts of that movement.

Meanwhile, Newt insists he’s a defender of free markets and a champion of the business community, but Mitt asks why he’s never personally participated in the capitalist adventure—spending his life as a college professor, politician, and a D.C. power broker and pundit.

When Gingrich attacks Romney as a “timid Massachusetts moderate” it’s not really about ideology—it’s about integrity. He knows that Mitt’s platform in this campaign is bold, substantive, and solidly conservative, so rather than questioning his position on issues, he challenges the reliability and authenticity of those commitments.

And when Mitt slams Newt as an “influence peddler” who is both morally dubious and dangerously erratic, it’s not really about corruption—it’s about character. He surely understands that Gingrich has already won a substantial place in the history books for orchestrating the conservative takeover of Congress in 1994, so rather than denying those great achievements he insists they’ve been compromised by ego, instability, greed, and grandiosity.

Both candidates took past positions that embarrass them today—yes, Mitt voted for Democrat Paul Tsongas in the 1992 New Hampshire primary, while Newt served as Southern regional director in the 1968 presidential campaign of Nelson Rockefeller—as much a villain to conservatives who remember him as any Democrat. ***But in this campaign, they’re similarly pro-life and pro–Second Amendment, supporters of drastic spending cuts and lower corporate taxes, opposed to overregulation and governmental expansion, and in favor of more oil drilling and a robust national defense.

When Newt delivered his non-concession speech in Florida (no, he never did acknowledge Romney’s victory), he presented a series of bold promises of what he planned to achieve in his first day as president. There wasn’t a single commitment he described that Romney couldn’t echo or endorse—though his more pragmatic temperament might lead him to shy away from pledging to get it all done in the first 24 hours.

With Mitt’s big win in the Sunshine State, the frontrunner would surely welcome a less vitriolic tone in the contests that lie ahead: as the likely nominee, he must recognize the possibility that more negativity could leave serious stains on his gee-whiz, nice-guy, Boy Scout reputation. The best way to avoid the mud wrestling of Florida would be to focus on the real possibilities of positive change. Newt could plausibly argue that he’s promised reform that counts as bolder and more sweeping, while Romney might answer that his strategy for achieving such goals counts as more plausible and realistic. Newt could stress vision, while Mitt might emphasize his executive ability and steady leadership.

This sort of discussion might lack the visceral, rock-’em–sock-’em thrills of the last 10 days of cage fighting, but it could actually serve to strengthen the GOP brand for the upcoming challenge to President Obama, making both of the leading contenders look optimistic rather than angry, big rather than small.

That high-minded tone might last only until Romney senses some new vulnerability in one state or another, or Newt finds his underfunded campaign drifting toward irrelevance and decides to recapture the spotlight with a new thermonuclear attack. At that point, Gingrich could well return to his eloquent indictment of his opponent (“You’re a con man!”) while Romney offers his usual witty ç (“You’re a creep!”).

Such intemperate exchanges will hardly count as edifying but they may, alas, be unavoidable.

Read More Daily Beast Contributors about the Florida Primary:Michael Tomasky: It’s Over for NewtJohn Avlon: This Race Is Far From OverMichelle Goldberg: Why Liberals Should Love NewtDavid Frum: Gingrich Knows It’s Over& More