Go back to 1991 when L.A. was torn apart by gang wars, the Bloods and the Crips were firing at each other in the streets, apartments in housing projects were going up in flames, the police committing terrible abuses. Now picture a striking woman dressed in pearls and a St. John knit suit marching up to a trailer filled with the baddest gangsters in the city as they try to work out a truce. That was Connie Rice, and she was there to help them.

“I was an absolute idiot,” recalls Rice during lunch at a hamburger joint in South Pasadena last month. “I must have looked like E.T. to those guys.” Still, she says after a pause, “I might be naive, but it works.” What she did was listen as they worked a code for killing that would limit the exposure of innocent bystanders (i.e., stay away from schools). Her bravado earned her the nickname “Lady Lawyer” by the gangbangers. Soon she was bringing their message to the authorities about police abuses and bullying tactics, and all the while working to break up the fights and end the violence.

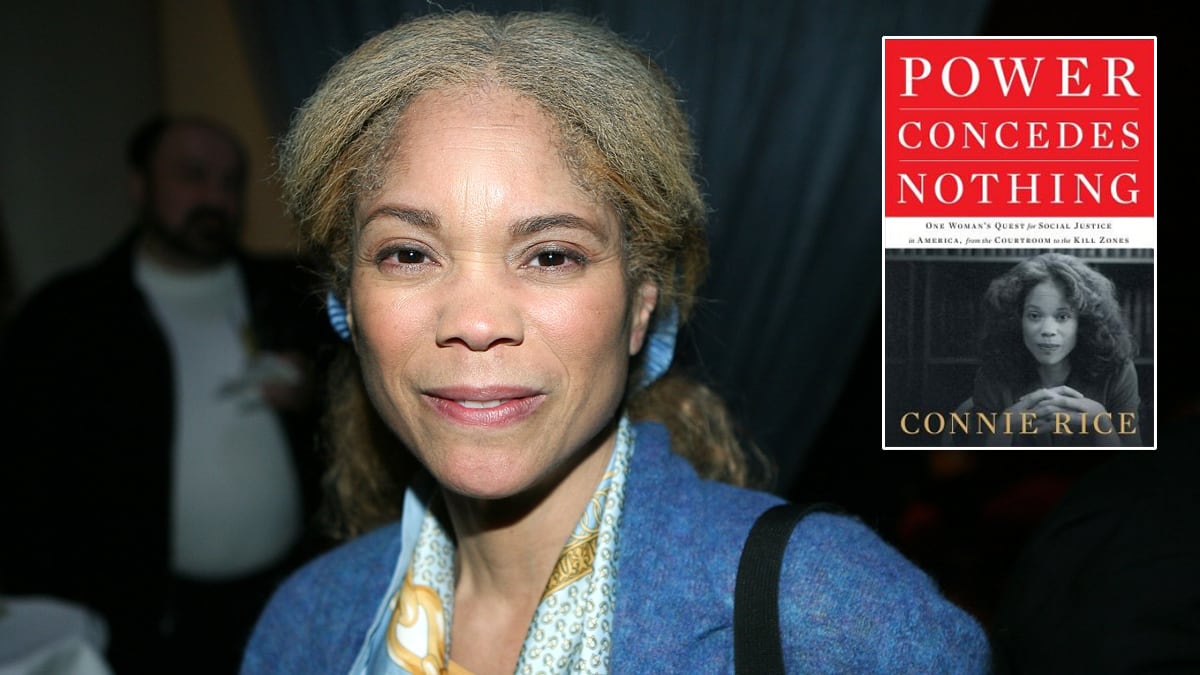

Thus began Rice’s 20-year odyssey on the violence-plagued streets of Los Angeles, a journey that she eloquently recounts in her new memoir, Power Concedes Nothing: One Woman's Quest for Social Justice in America, from the Courtroom to the Kill Zones. Thanks in no small part to her efforts, L.A. is a safer, quieter city than it was the day she walked into that trailer.

Since then, Rice, the Harvard-educated daughter of an Air Force colonel and second cousin of former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice, has advocated a radical approach to ending gang violence by working with the gang members to address the social, economic, and education failures that make this the only life for many. She devoted herself tirelessly to change on behalf of Los Angeles’s poorer citizens by becoming a virtual litigation machine, suing to hold the city to its own laws to redress discrimination, misconduct, and unfair public policy.

But her greatest fight was with the LAPD, a department she says was gripped by “systemic brutality, discrimination, and retaliation.” In her book, Rice paints a frightening picture of a department that discriminated against women and minority officers, raped its female recruits during the Police Academy, set up coworkers for beatdowns, planted evidence on traitors, and condoned secret police execution squads that retaliated against gang members who shot at them. “To find a more impressive campaign of malignant containment,” she writes, “you would have to go back to Bull Connor’s Birmingham, apartheid South Africa, or sectarian-racked Northern Ireland.”

Rice’s anti-gang strategy was to “move from a suppression-driven war on gangs to a public health campaign against the violence and trauma of the hot zones.” Obsessively focusing on gangs was wrong. It made them stronger. Her plan was to motivate L.A. institutions, families, and schools to mobilize themselves for safety and trauma prevention.

Her role as police agitator earned her the respect of former Los Angeles police chief Bill Bratton who, in 2003, asked Rice to write a report about the “lessons learned" from the Rampart CRASH scandal that roiled an LAPD anti-gang unit in the late ‘90s. He took “Connie’s recommendations” and made them his own. “My invitation for an ongoing partnership had received Bill Bratton’s RSVP.”

Rice continued to collaborate with Bratton—he called her in on the May Day fiasco, began to listen to her strategy about changing LAPD’s mindset, and even gave her a parking space at Parker Center—until he left the LAPD.

“He had done enough,” she wrote. “No matter how anyone looked at it, his had been an extraordinary run.”

Today, many of Rice’s recommendations are in place. Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa hired L.A.’s first gang czar and began offering artistic and educational programs that have drastically reduced crime in the surrounding areas.

And there are more Rices on the way. Since 2009 she has been training a new phalanx of activists to take up the fight at the first gang-intervention academy in the country. Staffed with former gang members and academics, including a sociologist and an epidemiologist, the Los Angeles Violence Intervention Training Academy is a 15-week course that treats gang activity as a disease that can be managed and defeated. The students are taught crime-scene protocol as well as how to act during gang funerals. “I would have sworn it wasn’t going to work,” said Rice matter-of-factly. So far, 200 students have graduated from the academy.

After all these years of conflict with the police and city authorities, people are listening to Rice. She now has the LAPD chief on speed dial. Next stop: tackling the cross-border drug war by creating the Urban Peace Institute where police, Homeland Security agents, and academics can study Mexico’s drug policy, the rise of the cartels, and their impact in the U.S.

For Rice, the great-granddaughter of Alabama slaves and slave owners, the fight against inequality started back at the age of 5, when she tried to coerce her brother into helping her free a lion from the Cleveland Zoo. As for her famous cousin, whom she met only in 1993, they have a lot in common. “We both inherited the Rice loner gene,” she writes about Condoleezza. “We escaped by doing what we loved—playing piano for her, doing tae kwon do for me, and shopping and exercise for both of us. We were overly close to our parents and emotionally remote. We were driven, self-sufficient, results-oriented, and professionally demanding. We had no patience for groups, dithering, or incompetence.” In short, these are women who get things done.

Looking back, Rice, who is now 55, says she wouldn’t have done anything differently. “My life would make most people have a nervous breakdown,” she says with a laugh. “I am exhausted. I look back at my time cards and I get tired looking at them.” But then she’s off to fight the good fight.