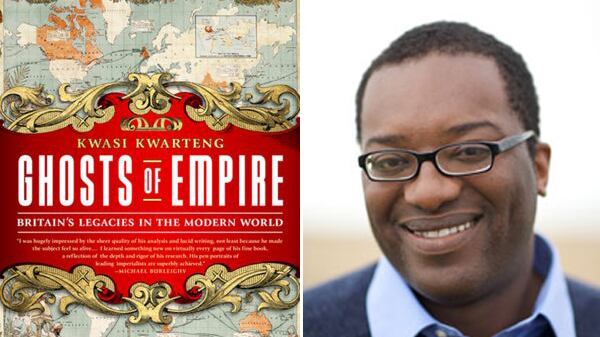

“I think interventions tend to be wrong. That doesn’t mean to say that every intervention has been a disaster, but it does mean that generally they tend to screw up.” I have met Kwasi Kwarteng, the British historian and Conservative member of Parliament, to discuss his new history of the British Empire, Ghosts of Empire, but it is clear that the last 12 years are on his mind. Kwarteng is one of a new cohort of politicians in Britain who combine political and literary careers, and it is fitting that we meet to talk books and history in Portcullis House, an office building for M.P.s near Parliament. While trained as a historian at Cambridge, Kwarteng is no ivory-tower dweller, but rather a man who believes in the power of history to inform, inspire, and challenge the present: “History is of all subjects the one which is most engaged with people’s perceptions of themselves, identity, politics, all those things which shape the modern world.” Moreover, for Kwarteng, history offers answers to some of the most pressing questions of our time: informing the book is the idea of “Should we intervene?” “Does it make sense to try and bring democracy to these countries?’” Kwarteng’s answer to those questions is skeptical and pessimistic. Using case studies from six different regions of the British Empire—Iraq, Kashmir, Burma, Sudan, Nigeria, and Hong Kong—he illustrates the ad hoc, ill-informed, incoherent, and frequently contradictory nature of British imperial rule.

Kwarteng’s targets in writing the book are clear: on the one hand is the school of thought that views empire as wholly bad, characterized by racist and exploitative policies and practices; on the other hand is the revisionist school, best exemplified by Niall Ferguson, which argues for the British Empire as a force for good that spread democracy, liberal values, and free trade throughout the world. For Kwarteng, both positions are flawed. “With this book I was really trying to move away from both of those approaches. I think they’re boring, too polarized, and not nuanced enough. I was trying to look at the thing as I saw it. That might be naive, but I did actually start off with the archives, without many preconceptions.” Over the course of his research, Kwarteng came to the conclusion that the British Empire was less driven by ideologies of racial superiority, the “civilizing mission,” or free trade, than by the whims and personal preferences of colonial administrators “on the ground.” While some writers, such as fellow Conservative M.P. Rory Stewart, have suggested that this was the great strength of the British Empire—good old British pragmatism—Kwarteng blames this “anarchic individualism” for leading to chronic instability in the empire.

This kind of history suggests as much the politician’s view of history—whereby historical events are shaped by great men—as the academic historian’s emphasis on the agency of individuals further down the pecking order. Kwarteng does, however, inject a note of skepticism and irony into his accounts of such imperial mainstays as Lord Curzon and Earl Kitchener. For Kwarteng, such figures are “great men, but deeply flawed.” It is no surprise that he cites Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians, in which Strachey irreverently punctured the myths surrounding various heroic figures of the Victorian age, as a key influence. This kind of multifaceted view of the men of empire reflects Kwarteng’s own relationship to empire. Whereas his parents came from Ghana, previously a British colony known as the Gold Coast, Kwarteng studied at Eton and Cambridge, exactly the character factories that he describes as manufacturing the men of empire. Like that other Old Etonian critic of empire, George Orwell, Kwarteng’s intimate knowledge of such thoroughly British institutions grants him both an empathy and a skepticism toward them and the men they produced: “I knew about these institutions because I had been a product of them, not a million years after they were producing imperial characters. I know about house spirit, I did Latin, I’d been schooled in a way that wasn’t that different … Even though I had awe and respect, some of these men were faintly ridiculous. They are outlandish and comic characters in many ways.”

Kwarteng’s book marks a return in popular history writing to a conservative skepticism, shorn of the ideological dimension of neoconservatism. It is, in this way, clearly a product of a post-Iraq world. Kwarteng is explicit about the impact of these interventions on shaping his worldview: “The idea that historians aren’t affected by what goes on around them I think is slightly fanciful. When I was in my late 20s, the big issue was the Iraq War … Lots of people of our generation were informed by it.” But while leftist critics of empire focus on the economic exploitation and injustice of foreign rule, Kwarteng’s critique focuses on human fallibility, uncertainty, and the limits of knowledge and power. Although he claims in his book that “the phenomenon of British rule must be understood in its own terms,” it is thus clearly a book about empire, not just the British one. There is a tension here: as a historian, Kwarteng wants to rescue the British Empire from being viewed in the light of current times, while as a politician interested in current affairs, he cannot resist drawing parallels with today. While in his writing he is keen to stress that it is a book about the mechanics of British rule, in conversation he reveals that he is thinking about imperialism in general: “I think that running empires as a way of ordering the world is a flawed model. There are all these uncertainty principles that we don’t know enough or have enough information about, and yet we’re always optimistic about the outcome of these campaigns. It’s a very similar debate to what happened in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

Kwarteng’s interest in current affairs extends to future book plans: “I’m very interested in the 2012 election, the decline of America since 2000, the financial crisis coupled to upsets in foreign affairs. Now, the final chapter on this can only be written in 10 years' time; America will either turn the corner and retrench economically or it may well be in secular decline. Time will tell.” Kwarteng may well have just written a book of history, but there is no doubt that he is a man with his eyes set firmly on the future.