The late Bob Bartley once remarked to me, "In my lifetime, the American people have never chosen wrong in a presidential election."

What he meant: even when his preferred candidate lost, as in 1992, Bartley blamed the loser for losing, not the public for rejecting a candidate who had failed his test of mettle. My guess is that Bartley would likely have thought the same way about 2008.

Key variable: "in my lifetime." On this President's Day, I do think about the ones who got away—the elections that went most disastrously wrong for the United States and the world.

I know many people would put 2000 on that list. I'll leave present-day controversies to the side for this holiday. I also look away from elections that produced a bad result that seems inescapable given the culture and mentality of the country at that time: if Andrew Jackson had never existed, the America of the 1830s would have invented somebody very like him. It took a civil war to win the day for Henry Clay.

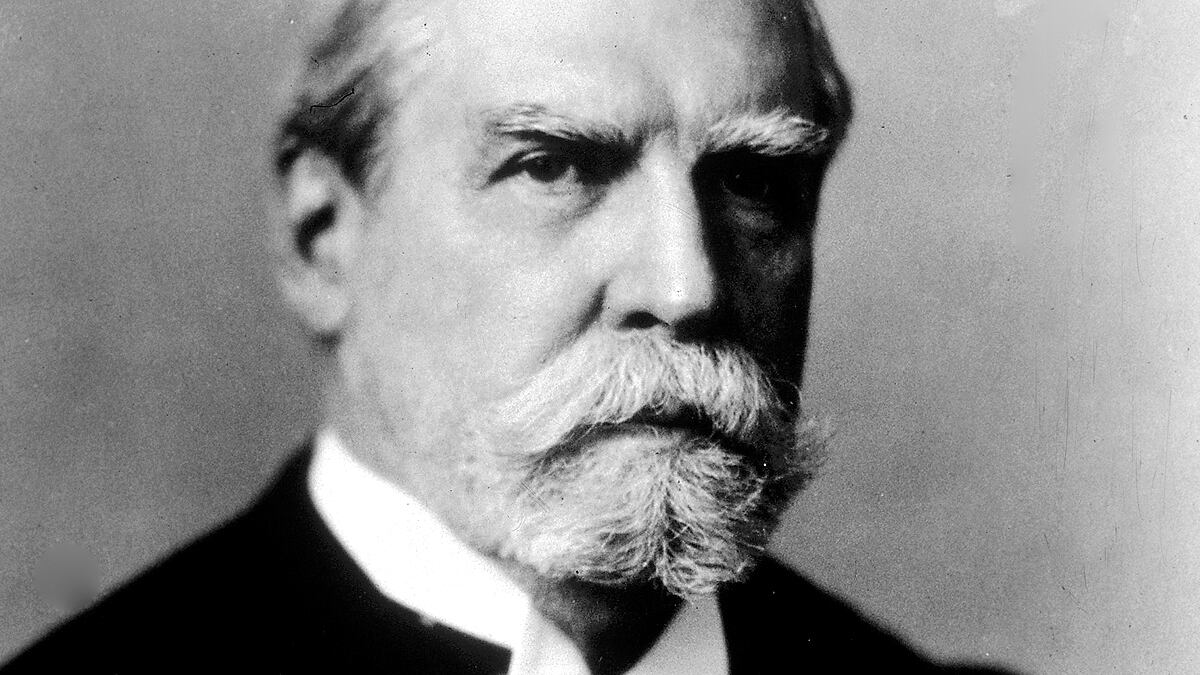

But here are the three elections to which my "what if?" mind does turn again and again: 1912, 1916, 1920. 1912 and 1916 were epically close elections; 1920 was decided by the accident of Theodore Roosevelt's premature death.

What if Roosevelt had disciplined himself in 1912 and supported the re-election of Taft? What if Charles Evans Hughes had prevailed in 1916? What if it had been Roosevelt and not Harding who won in 1920?

All of those things could realistically have happened, and they would have changed the shape of the 20th century. Had Taft won in 1912, the US would have entered the First World War earlier and ended it sooner (Taft and Roosevelt were ardent interventionists in 1914). Had Hughes won in 1916, the US would still have entered the war in early 1917—but better relations between Congress and president would have enabled the US to play a much more constructive role in shaping the peace.

And had Roosevelt won in 1920, rather than the weak and backward-looking Harding, the postwar reconstruction might have had a very different shape. We rightly condemn the Allied leaders of the 1920s for squeezing Germany so hard on reparations. We forget that the French and Belgians, who were doing the squeezing, were squeezing in large part to repay loans they owed to Britain—which could not afford to forgive those loans because it had to service its own loans to the US—which piously demanded British repayment while urging reductions in the reparations burden on Germany.

The only way to get to peaceful reconstruction was to begin with debt forgiveness by the US. That would have been a difficult sell under any circumstances, but impossible given the weak and unseeing leadership of Harding.

Leaders make a difference, which is why we do so honor the memory of those two miraculous leaders who appeared at the moment they were most desperately wanted: Washington and Lincoln. The astonishing availability of these two at the right time is only more powerfully illuminated by thinking how often in American history such leaders were absent when needed.