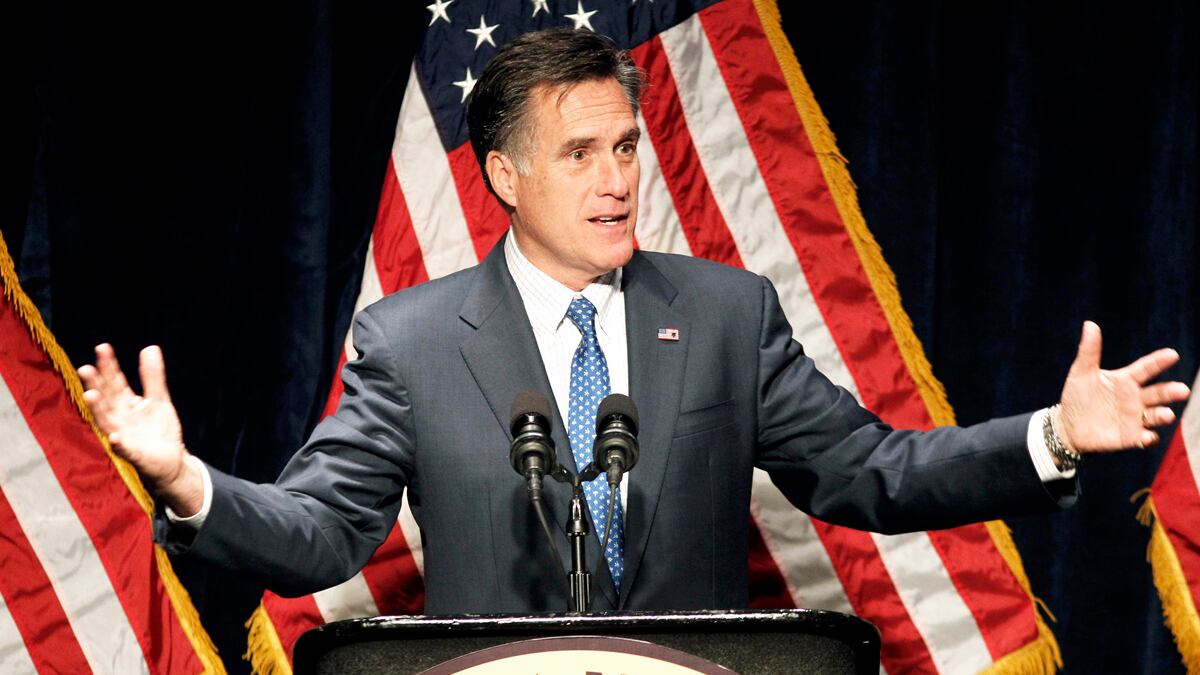

Inevitability and electability having failed him, Mitt Romney has decided to try seeming bold.

Romney is expected Wednesday to begin the rollout of his new tax plan, a proposal to lower tax rates by broadening the base through the elimination of some deductions and loopholes. Romney’s plan, to be fleshed out at Wednesday night’s debate and more fully at a big Detroit speech on Friday, may not seem especially dramatic—it’s sort of Simpson-Bowles ultralite—but for the Romney campaign, hitherto defined by its caution and calculation, it approaches audacity.

When Romney and his team designed a 2012 presidential strategy, they contrived a set of policy positions they called “a plan for governing,” as distinct from “a plan for campaigning.” The approach seemed suited to a candidate who, though unlikely to arouse voters’ passion, hoped to excite their imagination—asking them to envision a general election in the fall with Barack Obama having to defend the economy against a successful private-sector manager with a calm, reasoned plan for turning the country around.

One of the problems with this approach is that it underscored Romney’s carefulness in a primary environment that rewarded passion and daring (“9-9-9!”). For a candidate with a serious deficit of political pheromones—the harder Romney tries to “connect” with a crowd, the more stiffly antic he becomes—the relative timidity of his policy prescriptions suggested that a sense of entitlement, rather than vision, animated his candidacy.

Worse, Romney’s competitors all had ideas, however hare-brained they might at times have seemed, that clearly were designed for campaigning. Herman Cain had 9-9-9, and Rick Perry had the elimination of whole federal agencies, and each spent time atop the Republican heap. Newt Gingrich has churned out bold ideas as fast as he can pronounce them, his latest, unless it has already been supplanted, being a plan to bring gasoline prices down to $2.50 per gallon. Gingrich has twice surpassed Romney in the polls and fully expects to again.

For weeks, conservatives sympathetic to Romney have been urging him to bold action. Jennifer Rubin of The Washington Post, a steadfast Romney supporter, urged Romney to “push a tax reform plan that promotes wealth, simplifies the code, removes special giveaways for politically-connected industries and, nevertheless, is attuned to the plight of lower and middle income families.” Karl Rove wrote in his Wall Street Journal column that Romney “should become bolder in his prescriptions, presenting a confident agenda for economic growth and renewed prosperity through reforms of taxes, regulatory and energy policies.” Charles Krauthammer said on Fox News last week that Romney had to come up with a new idea, pronto, and that “it’s gotta be something large—tax reform, entitlement reform, some new idea. Otherwise, it’s treading water.”

Even within the Romney camp, at least one top strategist, seeing the traction that Cain got from his 9-9-9 plan, urged the formulation of some bold, new policy.

But bold wasn’t in the plan, nor was it in Romney’s political nature. As recently as last week, former New Hampshire governor John Sununu, one of Romney’s most forceful surrogates, told The Daily Beast that “big and bold is for teeny-weenie minds.”

Within the tightly contained Romney campaign circle, the “plan for governing” strategy seemed compelling. Critiques were drawn of the various fashionable conservative notions, which made them seem gimmicky at best, crackpot at worst.

In a lengthy discussion on the subject earlier this winter, Romney policy chief Lanhee Chen told Newsweek that while a flat tax, such as that proposed by Gingrich, has wide appeal, “when the rubber hits the road, you have problems.” A truly flat tax, Chen said, could only work if nearly all deductions were eliminated—and people are attached to their pet deductions.

Elimination of federal agencies sounded bold but couldn’t prudently be planned from the perspective of a campaign; the data have to be understood properly before slashing begins, and “understanding the data begins with being in office.”

Even Romney’s longstanding plan to zero-out capital-gains taxes is attenuated, applying only those earning below $200,000, a break that excludes, Chen concedes, the big-investor class. Romney says this policy is aimed at helping middle-income Americans, but there is clearly an element of self-inoculation here. Romney, who earned $21.7 million from investments in 2010, and paid less than 15 percent in capital gains on those earnings, could hardly campaign on eliminating capital gains altogether.

Romney’s “new” tax plan is not really so new. He has long expressed sympathy for the Simpson-Bowles tax suggestions, and a month ago told CNBC’s Larry Kudlow, who broke the story about Wednesday’s tax plan, that his team was working on some version of it. “It’ll be ready at some point,” Romney said, not sounding like a man very much in a hurry.

He’s in a hurry now, his inevitability frayed to a thread, and rattled by the unwelcome surprise of a Santorum surge in Arizona and Michigan (where Romney had long assumed a native-son advantage). His Friday speech before the Detroit Economic Club is so fraught with potential consequence that the venue has been changed to Ford Field, where the Detroit Lions play.

It’s a big arena, and Romney desperately needs a big moment. For all of his caution, he has shown himself able to deliver when his back is against the wall. Against the common wisdom, Romney whipped Gingrich on the debate stages of Florida. Now he will try to convince voters that he can also compete in the arena of ideas.