Though she never mentions Thomas Friedman by name, Katherine Boo’s superlative new book, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, is a direct refutation of Friedman’s rose-colored view of contemporary India as a land of upwardly mobile call-center workers happily swiping smartphones as they out-study and out-work the complacent American middle class.

After presenting hundreds of pages of unsentimental detail about the crushingly difficult lives of garbage-sellers, public toilet-cleaners, thieves, and prostitutes living in the Mumbai slum of Annawadi, Boo insists in her author’s note that no reckoning of the global economy is complete without considering the plight of those too hamstrung by fate to take advantage of its offerings. Other writers’ enthusiastic profiles of Indian tech entrepreneurs elide “early privileges of caste, family wealth, and private education,” she argues, noting as well that instead of speaking forthrightly about globalization’s failure to alleviate poverty, “politicians held forth on the middle class.”

That refusal to acknowledge the systemic, deeply unfair nature of intergenerational poverty pervades the American dialogue on class and opportunity, as well. Hence Mitt Romney’s much-maligned (and demonstrably false) statement that “the very poor” don’t need political attention because “we have a safety net there … I’m concerned about the very heart of … America, the 90 percent, 95 percent of Americans who right now are struggling.”

As in India, of course, the most desperate struggles for dignity in the United States happen not in the vast middle of the social spectrum, but at its lower fringes, where 16 million American children experience what the U.S. government calls food insecurity, defined as not having “enough food for an active, healthy life.” Moreover, nearly half a million kids under 5 have elevated levels of lead in their blood, which can lower IQ and lead to behavior problems like ADHD—and which is the direct result of inadequate housing and uneven access to health care.

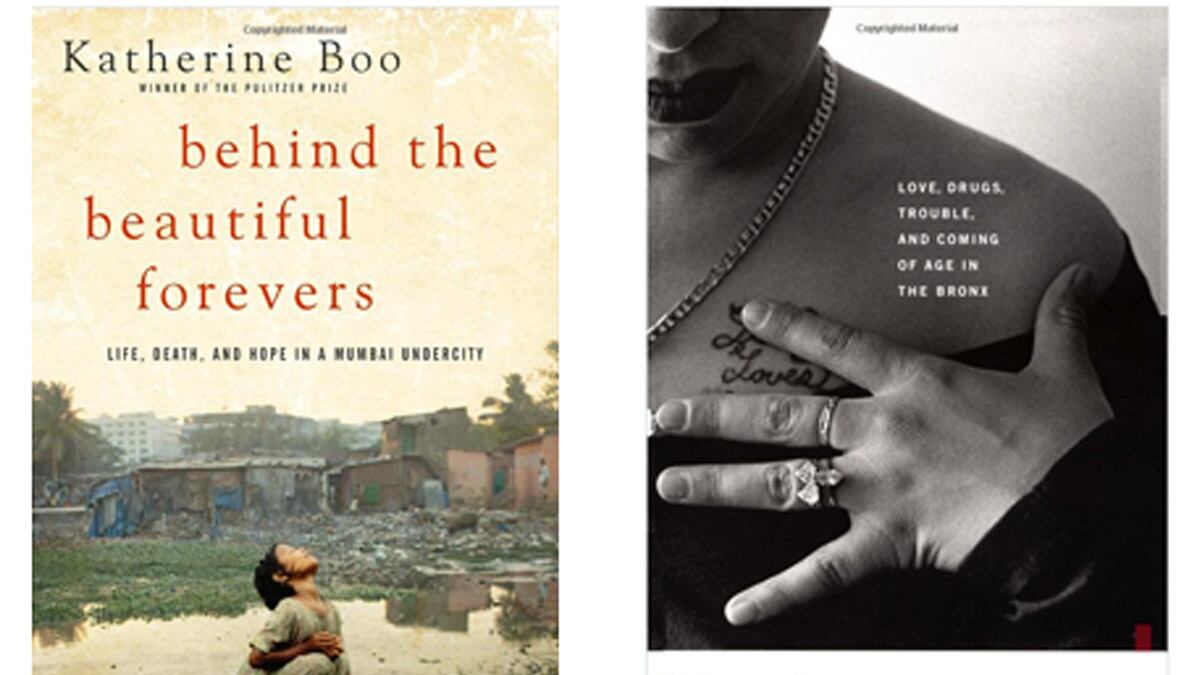

Statistics like these “sometimes have a tenuous relationship to lived experience,” Boo writes. Thankfully, there is a work of narrative nonfiction that does for American poverty what Behind the Beautiful Forevers does for the Indian variety: personalizes it, through the unforgettable stories of flawed, but deeply sympathetic real-life characters. That book, Random Family, is Adrian Nicole LeBlanc’s 2003 triumph of narrative nonfiction, the result of a decade spent reporting on one extended family living in the East Tremont section of the South Bronx.

While working as the fiction editor of Seventeen magazine in the early 1990s, LeBlanc wrote freelance pieces for the Village Voice about the trial of Boy George, a brilliant and violent 22-year old heroin dealer. She became fascinated with the lives of Boy George’s many teenage girlfriends, especially Jessica, a vivacious party-girl who briefly lives like a Hollywood ingénue—ski vacations, limo rides, four-star dinners—before the legal system breaks up Boy George’s business and thrusts Jessica back into the life her mother led before her: that of a high-school dropout single mom with few employment options, facing prison time for her own involvement in the drug trade.

LeBlanc provided Boo with a warm blurb for the back cover of Behind the Beautiful Forevers, and the affinities between the two books—set 7,800 miles and two decades apart—are astonishing. The way Annawadi’s savvier operators make a business out of government corruption, skimming off the top of generously funded anti-poverty efforts, is not dissimilar from the way the drug economy operates in American inner cities. “Corruption was one of the genuine opportunities that remained” for personal advancement in a Mumbai slum, Boo observes; several of the garbage-pickers she profiles accept their dirty lot in life only after giving up on dreams of a good education and clean, service-sector work in nearby luxury hotels.

In LeBlanc’s account of the South Bronx, smart young men like Cesar, Jessica’s brother, turn to drug dealing as a rational response to a neighborhood devoid of opportunity as most of us know it, one that lacks quality schools and decent jobs. In both books, individuals who idealistically resist the financial pull of illegal commerce eventually learn that, as Boo puts it, “there were millions of other bright, likable, unskilled young men in this city”—and not nearly enough jobs in the legitimate economy to go around. (Only about half of Mumbai residents hold formal jobs, while in New York, a third of all low-income households have experienced unwanted job loss, wage reductions, or hour reductions over the past year.)

It might seem blithe to compare American poverty to its Indian counterpart. It’s true, for example, that even the poorest Americans don’t fry rats or sewage-swimming frogs for dinner, as some residents of Annawadi do. Just about every American child attends primary school and learns to read and write, while 35 to 60 million Indian children do not attend school at all, and a quarter of India’s population is illiterate. In the United States, tuberculosis has been all but eliminated; in India there are 2 million new cases annually, some among slum garbage collectors like one man Boo describes, whose eyes turn from sickly yellow to bright orange before he dies.

But like Behind the Beautiful Forevers, Random Family captures the reality of life for far too many Americans: that no amount of optimism, ambition, or hard work can guarantee an escape from poverty. Perhaps the most heartbreaking element of both books is the way in which hope operates as a sort of fallacy; how stories of individual college graduates, rap stars, and kingpin drug dealers allow the ordinary poor to dream of advancing “from zero to hero,” as the Annawadis like to say—despite the overwhelming force of the systemic constrictions in their lives. Random Family ends with Jessica’s 16-year old daughter having her own baby out of wedlock; in Behind the Beautiful Forevers, the industrious Husain family fails to build their dream house in the suburbs, and even the smartest and most beautiful girl in Annawadi, the college student Manju, can’t attract a middle-class husband.

“It is easy, from a safe distance, to overlook the fact that in undercities governed by corruption, where exhausted people vie on scant terrain for very little, it is blisteringly hard to be good,” Boo concludes. LeBlanc’s corollary: “When you were poor, you had to have luck and do nearly everything absolutely right” if you had any chance at all of transcending the conditions into which you were born.

That sort of empathy for the poor is in short supply in our political and policy debates, but without it, we won’t come close to understanding the depth of the poverty problem every globalized nation—including the United States—needs to address.