As the GOP contenders try to recalibrate their campaigns in the wake of Super Tuesday, it ought to be obvious that Mitt Romney’s undeniable “Southern Problem” represents a far less serious challenge to his ultimate success than Rick Santorum’s deep difficulties with the 74 percent of the country that rejects the label “white, evangelical Christian.”

As the Republican nominee in November, Romney would easily defeat Barack Obama in the strongly conservative, Southern states that are giving him fits in the primary process. But if Senator Santorum somehow defied the odds and led the GOP ticket in the fall, he’d only amplify his current failure to build support in any electorate not dominated by born-again voters.

In this week’s Super Tuesday primaries, Romney lost three Southern states (Georgia, Tennessee and Oklahoma), following his crushing defeat by Newt Gingrich in January’s South Carolina vote. He’s won two of the most populous states of the old Confederacy—Florida and Virginia—but both lopsided victories reflected special circumstances. In the Old Dominion, only Ron Paul qualified for the ballot to oppose the Mittster, and Florida’s ethnic and cultural diversity makes it uniquely cosmopolitan among all states below the Mason-Dixon Line.

Romney will face obstacles in next week’s primary battles in Mississippi and Alabama, but he could still pick up a few delegates—as he has in every Southern contest to date. Ed Kilgore of the New Republic points out that five Southern states have voted so far, selecting a total of 258 delegates to the national convention, and Romney has won at least 115 of them, giving the lie to the notion that he enjoys no support in Dixie.

Moreover, none of the Southern states where Romney lost to Santorum or Gingrich represents a significant battleground for the fall campaign; any Republican should easily prevail against Barack Obama in South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and Oklahoma. Last time, McCain beat Obama by 15 points in Tennessee and a whopping 32 points in Oklahoma. No one expects the Democrats to turn around these margins, even if the GOP nominee is perceived as wobbly and uninspiring.

The crucial Southern swing states are those that McCain actually lost (Virginia and North Carolina) and nearly lost (Missouri)—and all three battlegrounds abound in the well-educated big city and suburban voters that connect most reliably with Romney and present profound problems for Rick Santorum.

The biggest obstacle to Rick Santorum’s general election success would be his consistent inability to gain traction in any electoral struggle not dominated by self-described “White evangelical/born-again Christians.” These voters represented 56 percent of the total caucus participants in Iowa, 74 percent in the Oklahoma primary, and 72 percent in Tennessee—the sites of Santorum’s three most significant victories to date. In Iowa, typically, he beat Romney by more than 2 to 1 among this majority of deeply committed Christians, but lost everyone else by nearly 3 to 1—producing a virtual tie with Romney. (Santorum won the final count by 34 votes.) When asked to name the most important issue in the election, only 13 percent of Iowans specified “abortion,” but these pro-lifers chose Santorum by a devastating margin of 58 to 7 percent. On the far more significant issues of “the economy” and “the budget deficit” (selected by a combined 76 percent as top issues), Romney won decisively.

In fact, it’s possible that in all of the seven states Santorum has won so far, white born-again Christians comprised the majority of the GOP electorate. Missouri, Minnesota, North Dakota and Colorado offered no exit polls for this year’s primaries and caucuses, but results from the general election of 2008 show their heavy representation of evangelicals, from 21 percent (Colorado) to 39 percent (Missouri) of all voters. Since born-again Christians identify overwhelmingly with the Republican Party and vote disproportionately in GOP primaries and caucuses, it’s not unreasonable to take those proportions from the last presidential election and to double them, to try to estimate the percentage of born-agains in recent primaries and caucuses. By this standard, all Santorum states except Colorado would have shown an evangelical majority—and in any event a far higher percentage than the 26 percent of evangelicals among all voters in 2008 (who loyally gave 73 percent of their vote for John McCain).

Ohio, which split down the middle on Super Tuesday between Santorum and Romney, also showed itself closely divided between evangelicals and others, with 47 percent of Republican primary participants identifying as white evangelical or born again. These religious cadres marched with Rick Santorum, but he lost badly (44 to 30 percent) with all others. Similarly, only 29 percent of Ohioans agreed with the proposition that it mattered “a great deal” if a candidate “shared their religious beliefs,” but those voters gave Santorum their hearts and their help (53 to Romney’s 20 percent) and constituted the solid core of his Buckeye State support. Without that base, he would have lost badly rather than narrowly in the most significant primary battle to date.

The point is that in major upcoming primaries (Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, California) Santorum will face a far less evangelical electorate than in the states in which he previously prevailed, and in the general election Democrats and independents will naturally flood the polling places, diluting the influence of Christian conservatives still further. With three quarters of overall voters telling exit pollsters they don’t consider themselves white born-again Christians, Santorum would somehow need to build support with religious groups he’s lost badly in the campaign so far. Even among his fellow Catholics, the former senator loses repeatedly to Romney (and to Gingrich), and with growing numbers of unaffiliated secularists (now estimated as 15 percent of the overall population) he fares much worse.

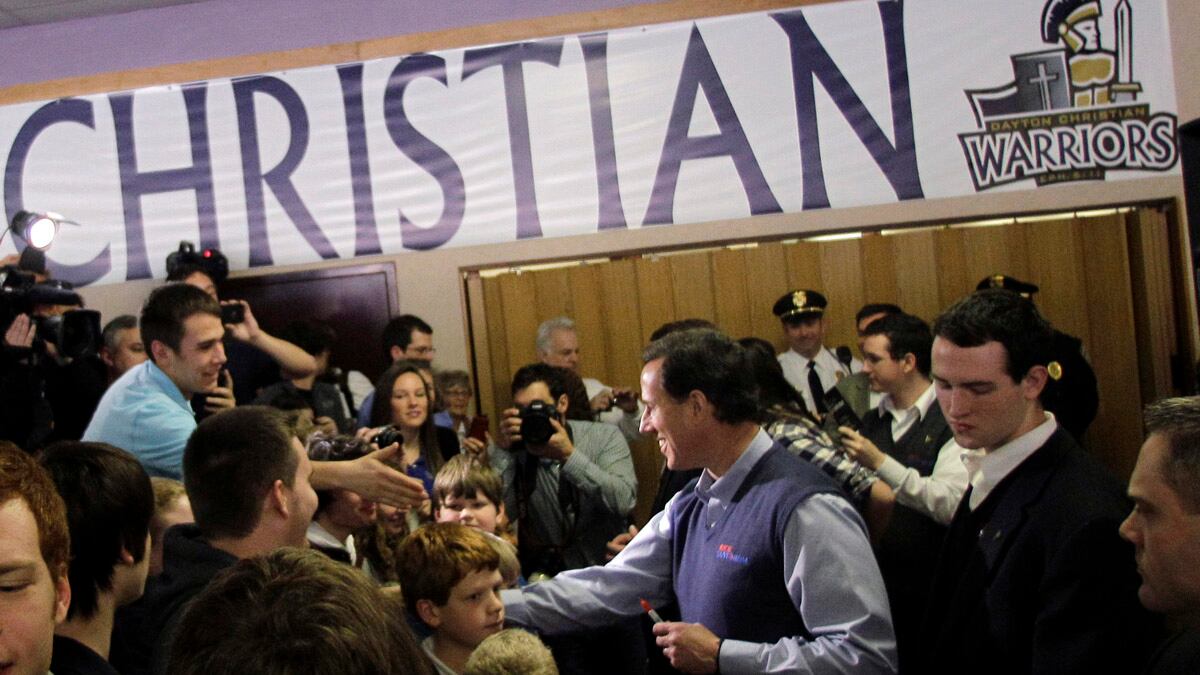

Santorum may attempt to emphasize economic issues over cultural concerns in a conscious effort to broaden his base, but it’s too late to change the distinctly religious nature of his campaign. Santorum’s twice-repeated declaration that John Kennedy’s insistence on strict separation of Church and State made him “want to throw up” will continue to haunt his candidacy and undermine any effort to alter the fervent, churchy, true-believer tenor of Righteous Rick’s crusade.

Going forward, Santorum may enjoy continued success among GOP voters in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Kansas and even Texas, but when the battle moves to less religiously committed corners of the country (especially in the fall campaign) his drive for the presidency will hit a wall—if not the traditional barrier separating church and state that he so energetically despises, then at least an impassable road block dividing his dreams of power from obvious political reality.