SPOILER ALERT: What you are about to read may not be easily summarized in a tweet.

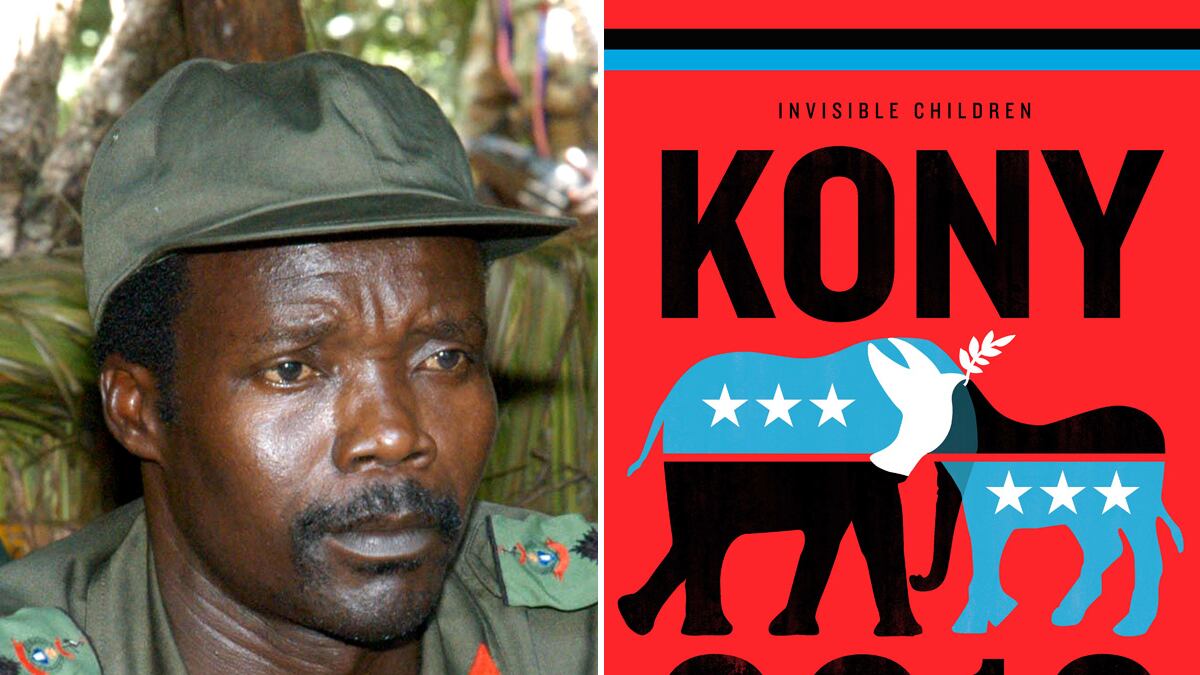

Therein lies the problem with that superviral Kony2012 campaign that launched Monday with the release of a 30-minute documentary juxtaposing a cute blond kid in Southern California with a bunch of terrified ones in Africa; a video that by Thursday had already reached 38 million views; a hashtag of #stopkony that is still trending on Twitter, along with #Uganda and #Africa and a Facebook page with more than 400,000 “likes” and celebrity weigh-ins from Lady Gaga to Justin Bieber.

“Stop Kony” is a simple, powerful slogan, a message bolstered by a beautifully shot, powerful video, along with a logo, social-media campaign, winsome founders, and young people all over the world convinced that if they themselves can’t drop everything and sign up for this cause, they can at least re-tweet it. Even if they have no idea what’s really going on in Uganda.

First, here’s what’s going on in Uganda, according to this post four months ago from Foreign Affairs’s Mareike Schomerus, Tim Allen, and Koen Vlassenroot: during three decades of brutal war, Joseph Kony led the violent central African rebel group the Lord’s Resistance Army, comprised largely of kidnapped children, to all sorts of horrifying acts against their own people. Now, the LRA’s ranks are depleted and Kony is on the run. His forces no longer operate in the country, at least not as the LRA, though he remains at the top of the International Criminal Court’s Most Wanted List, indicted for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

So, one of many problems with the heart-rending film so many “slacktivists” are now posting on their Facebook pages with urgent messages to #stopkony is that he’s pretty much stopped, even though he has yet to be brought to justice for many years of war crimes. The video brushes past this fact, after 10 minutes of a self-indulgent backstory about some hipster dude from Southern California named Jason “Radical” Russell, who was shocked—shocked, I tell you—that people in Africa were slaughtering each other; noting, astutely, that “If this happened in America, it would be on the cover of Newsweek.”

Well, obvi. But then the video moves into a call for action, using Russell’s son, “Gavin Danger Russell,” as the way to remind other white people that it could just as easily be their children being kidnapped and mutilated, even though that’s not really true. By the end of 2012, Russell insists, Kony must be stopped, because the video will “expire” at that point.

Which means what, exactly? That’s not so clear. Russell notes—quickly—that “Uganda is relatively safe” now, but insists that “Kony is still out there, and he had to be stopped.” This is urgent, Russell says, because President Obama sent in 100 armed advisers to Northern Uganda last fall, on the pretense that they would help the Ugandan government track Kony down—even though he’s not there anymore. Without major public awareness (and stacks of donated cash) lawmakers could pull the plug on the whole operation, Russell claims—even though no one is threatening to do so now.

And at that, with some gut-wrenching imagery, the glossing over of a few facts, a movement was born on Monday—or reborn, as the case may be. Russell’s nongovernmental organization, Invisible Children, has actually been around for nine years now, and it’s a full-fledged $13 million operation, not a fledgling movement.

Which may explain why Invisible Children is so determined to keep this cause alive, even as Kony’s cause is all but dead. Russell and his two cofounders earn nearly $90,000 apiece in salary, and of the $13 million they brought in last year, only 32 percent of it made it back to Uganda, according to financial statements posted on its website. The highly regarded watchdog Charity Navigator gives the NGO a ranking of three out of four stars, downgrading it largely because there is no outside, independent board auditing its books—a problem, say critics, because of the flood of hard-to-document cash donations the charity receives.

So as quickly as the Kony2012 movement went viral this week, so have the NGO’s many and loud critics piped up, accusing the founders of exaggerating an outdated cause in order to line their own pockets. “Invisible Children Inc. directors are collecting financial donations and laughing all the way to the bank with your money,” proclaims the website, which is home to a collection of myriad Invisible Children criticisms.

An email inquiry from The Daily Beast on Thursday prompted an auto-reply that explained the NGO has been swamped since the video came out. But Invisible Children has heard enough of these complaints to warrant an official statement on its website. It’s “in the process of interviewing board members,” for one, and even though the LRA left northern Uganda in 2006, it remains active in Congo, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan, writes communications director Noelle Jouglet. “Invisible Children’s mission is to stop Joseph Kony and the LRA wherever they are and help rehabilitate LRA-affected communities,” she said.

As for the financials, which can be found here, Jouglet notes that only 16 percent of the donations it receives goes toward administration and management costs.

What to make of all that? First, the Uganda question: Joseph Kony is, to be sure, a bad dude. And even though he’s been out of Uganda for six years and his army, which has over three decades turned some 30,000 kids into killers, is now down to a few hundred stragglers, it’s hard to argue against hunting him down.

But the authors of last November’s Foreign Affairs article, among others, argue that won’t necessarily accomplish much, that the rebels who fight for Kony will just go sign up with some other rebel group if their leader is captured and keep killing people in whatever country they’re operating in.

There are rampant complications with any effort to “stop Kony,” too. Invisible Children claims that much of its resources go to building schools, funding scholarships, and enhancing communications equipment in Uganda, which are all worthy endeavors. But the central effort of the cause is to “Make Kony Famous” via this massive public awareness campaign, which means to put pressure on President Obama and congressional and world leaders to invest in hunting him down. That Obama agreed to send 100 advisers to Africa for this purpose is either a response to this urgent (and maybe unnecessary) call; it signifies that the president’s people actually see this guy as a threat; or that there’s something else going on entirely, connected perhaps to the recent discovery of oil in the region, or a payback for Uganda’s cooperation in the war on terror.

Taking sides with Uganda’s government isn’t an easy decision, though. President Yoweri Museveni is a quasi-authoritarian ruler in a country with widespread corruption, and his troops have committed plenty of atrocities, too. “The government forced the region’s population to relocate into what were effectively concentration camps,” wrote Schomerus et al. “There, they were poorly protected from attacks, and faced dreadful living conditions.”

Many of the military efforts to fight the LRA have “served mostly to kill efforts to keep beleaguered peace talks going,” the authors continued. “And, far from neutralizing the LRA, they prompted a strategically effective and ferocious response. In January and February 2009, the LRA abducted around 700 people, including an estimated 500 children, and killed almost 1,000.”

Then, there are those questions about the charity itself. Is it enough to only spend a third of your money in the country you’re trying to help, and to pay your founders a generous salary? And what about this business of an outside board? Leslie Lenkowski weighed in on these issues in an interview with The Daily Beast. He’s a clinical professor of public affairs and philanthropic studies at Indiana University, and he’s working with one of his classes right now on a project for Charity Navigator.

The salaries aren’t exorbitant, Lenkowski said, nor is the amount of money spent on “people” expenses, from travel to film production work—especially for an NGO whose principal purpose seems to be making snappy videos that raise awareness.

“Charities are in the people business,” Lenkowski said. “They use people to get things done, whether it’s feeding the hungry or in this case creating a buzz to mobilize public opinion against the LRA.”

Not having an outside board auditing the books is a problem, though. The charity’s audited financials were prepared by an independent accountant, but Charity Navigator deducted points because it didn’t have an audit oversight committee. Without that, he said it’s harder to place any stock in what Invisible Children is reporting.

Lenkowski wondered, for example, how the NGO acquired $3.4 million in “program service revenue” last year. He said that’s often code for money earned as interest in micro-lending programs, which is one of the NGO’s functions. Micro-lending is coming under increasing scrutiny, Lenkowski said, for charging exorbitant fees and rates. Only a closer look at the financials would reveal where that money came from.

But who has time for any of that? So just go back to tweeting #stopkony, and everything will surely work itself out.