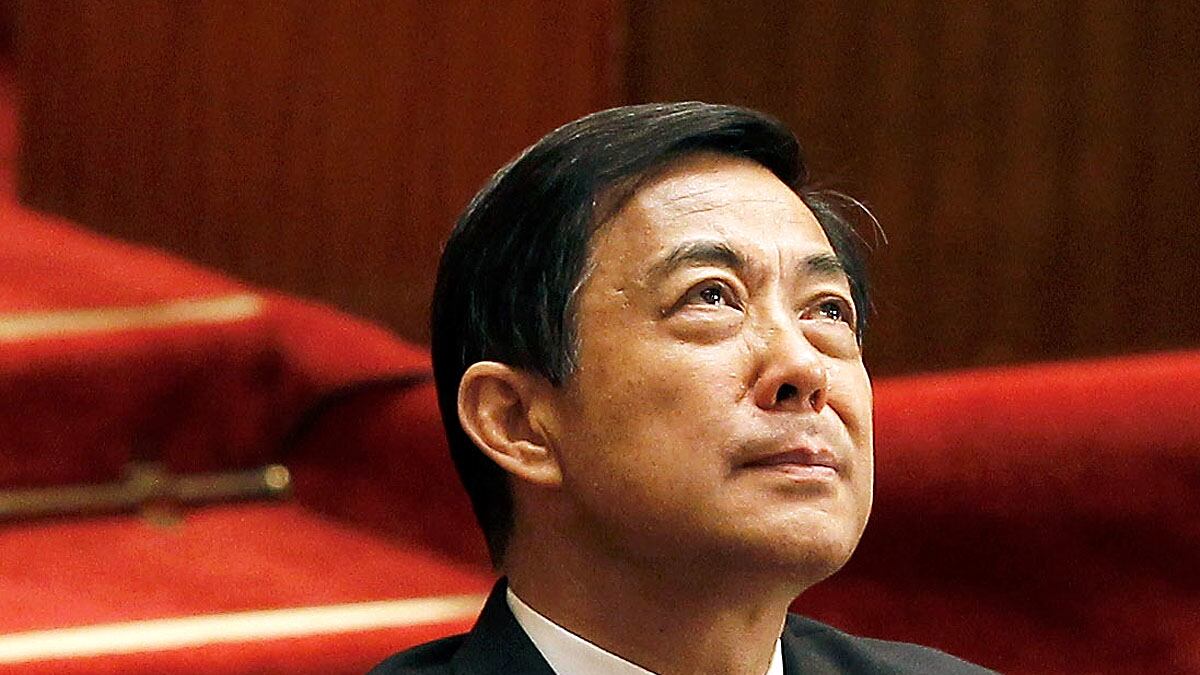

Today’s unceremonious dismissal of Bo Xilai, the powerful and charismatic Party Secretary of China’s giant southwestern megalopolis of Chongqing, is a political earthquake that will send shockwaves across China.

Bo was bigger even than his big job: the most powerful and persuasive advocate in China for leftists and neo-Maoists who believe, as Bo pointedly observed in a Beijing press conference just last week, that if “only a few people are rich” at the end of a decade of breakneck economic growth, “then we are capitalists, we’ve failed.”

Bo touted his “Chongqing model” as a happy marriage of communist morality, social equality and economic efficiency, breaking growth records through booming state-owned corporations while spreading some of that wealth to workers in progressive socialist housing, education and health programs. He reveled in Maoist-style slogans. His “Sing Red and Strike Black” campaign, an odd juxtaposition of Maoist revivalism with ruthless crime-busting, struck a chord with many Chinese angered both by corruption and by the enormous gulf between rich and poor that many blame on economic liberalisation.

Bo also carried the clout that comes from being one of the “princelings”—sons of the big heroes of the 1949 revolution, considered until very recently to be untouchable. He was strongly placed for the ultimate political elevation this October, expected to secure one of the nine seats on the all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee—a committee his detractors (who call him a “little Mao”) feared Bo would come to dominate. And indeed, there is a whiff of the 1976 fall of the Gang of Four in Bo’s abrupt defenestration.

It is a measure of the difficulty Bo Xilai’s ideological challenge posed to the Beijing leadership that it clearly felt compelled, the day before the axe fell, to make the case against him to the nation, under the authority of no less a figure than Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao. In a broadcast press conference, Wen deliberately studded his speech with clues that Bo’s political fate was sealed.

Party press conferences in China are not supposed to be exciting events—certainly not mere months before the leadership hands over power to the next generation, and all cadres must stage impressive displays of party unity. So Wen Jiabao’s three-hour encounter with foreign and national journalists at the end of the National People’s Congress on Wednesday would, at any time, have been nothing short of extraordinary. Here was China’s Prime Minister conjuring up the horrors of Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution, declaring the Arabs’ desire for democracy to be an undeniable force, challenging the Chinese to see the urgency of political reform and delivering a barely veiled attack on the “Red Princeling” Bo Xilai. Wen’s speech made it was plain to every person watching that, as far as he and his fellow modernizers were concerned, there is no going back; China is on the road to a future very different from its Maoist past.

Wen’s rebuke was as dramatic as Chinese politics gets--and he is correct that China’s future hinges on the outcome of the battle within the Party itself. Live on national television (and therefore ruling out any subsequent gloss or watering down for public consumption), Wen chose—evidently, as it emerged the following day, in joint decision within the top leadership—to use his prime-time, once-a-year press conference to take direct aim at Bo Xilai, and signal his opposition to Bo’s promotion to the Politburo standing committee.

With a bluntness almost unheard of in China’s stiff official discourse, Wen used this most public of platforms to describe the Cultural Revolution as a “tragedy”—and one that, without urgent political reforms, “may happen again”. In contrast, Bo has made the idea of a “Red Culture” revival central to his philosophy.

Wen was vague about what political reform would look like in China—with only a year left of his decade in office, specifics were not the point. Wen’s purpose was to use all the considerable influence remaining to him to support the cause of liberal reform against the leftist wing of the party championed by Bo.

That, and to tell the nation: “Watch out: this man is dangerous.” Wen responded strongly in the broadcast to questions about the dramatic tale that has riveted China since the news broke last month—the flight to a US consulate and subsequent detention in Beijing of Wang Lijun, the flamboyant Chongqing police chief and famous crimebuster who was for years Bo’s strong right arm. Discussion of that drama has crackled in almost uncensored form across the Chinese blogosphere. Wen sternly intoned that the Chongqing Party Committee (headed by Bo) must reflect seriously on the “incident” and that the government was investigating the case with utmost gravity. He added: “an answer must be given to the people and the result of the investigation should be able to stand the test of law and history.”

What Wen did not add is that Beijing has in fact been investigating Chongqing for nearly a year now, long before Wang was suddenly purged by his boss and fled Chongqing in fear for his life. Beijing has accumulated evidence that Bo and Wang’s “strike black” campaign, officially against organised crime, has also served as cover for nabbing thousands of extremely rich businessman. Purportedly held in secret prisons and interrogated under torture, many were given long prison terms or executed. Many had their assets confiscated—a neat way, critics say, to finance Bo’s vaunted housing for the poor and leave enough over to pay for his son’s red Ferrari and to buy allegiance.

The “smash black” campaign also served as a way to smear the stigma of corruption on Wang Yang, the liberal Guangzhou party boss who is also in line for a Politburo standing committee slot, by allowing people to come to the conclusion that Wang must have allowed these businessmen to flourish when he held Bo’s Chonqing job. In his press conference,Wen pointedly praised Wang Yang’s tenure.

Professor Tong Zhiwei, who conducted Beijing’s investigation, is by far the leading Chinese authority on law, administration and constitution, posted at the prestigious Jiaotong University in Shanghai. His report, submitted to the leadership last autumn and also discussed by him on television, is damning. The primary goal of “strike black”, he concluded, was to “weaken and eliminate” private enterprise, “thereby strengthening state-owned enterprises or local government finances”. Its main impact, he wrote, was not on the Chongqing mafia, the ostensible target, but on the wealthy elite stripped of their money, their power and even their families--many of whom were also hauled off to detention. One of these millionaires, the businessman Li Jun who is now a penniless exile, has described in detail the torture he says he suffered under the “new red terror”, presided over by Bo and the police chief whom Bo so hurriedly demoted last month. Another mogul, Zhang Mingyu, who claims to possess incriminating tapes on the methods used against detainees, was seized by Chongqing police in Beijing last week.

If Bo had hoped to make Wang Lijung the fall guy as the net began to close around him, that move spectacularly backfired. Beijing may now decide to throw the book at Wang--and to publish the grisly facts about the alleged torture, extortion and other unlawful methods used in Chongqing, as premier Wen hinted in his promise to make public Beijing’s investigation of the Wang affair. Such revelations, if true, would destroy both Chongqing men. Bo may well be in line for worse punishment than merely losing his job. To break the grip of the left, Bo must be discredited. This struggle is more than a battle between two ambitious contenders for leadership roles. The sacking of Bo Xilai is a pre-emptive move to ensure that the liberal line prevails in China, not the statist model. By dramatically invoking the dark decade of the Cultural Revolution, Wen Jiabao has further put pressure on the hitherto reticent Xi Jinping, China’s heir presumptive, to line up, unequivocally and here and now, with the forces of modernisation.